I went from simply enjoying horror movies to being a hardcore fan of them after I saw The Blair Witch Project during its theatrical release in 1999. I felt an energy and excitement around its story and mysterious creation that I had never felt about any movie before. For a couple of weeks after, between visiting its cryptic website and reading mystified reviews, I wasn’t sure whether it was fact or fiction. It was my first taste of the found footage genre and came at a time when the digital age and access to the internet had begun but hadn’t become so ubiquitous as to remove almost any chance of surprise or confusion when it came to media projects. Our collective abilities to both navigate the digital landscape and to gauge the trustworthiness of the websites we landed on were in their infancy. Not to mention the fact that we had never experienced on a mass scale the pop-culture disinformation campaign built around the Blair Witch universe.

Calling it disinformation isn’t a criticism now and I certainly wasn’t complaining at the time. The first gift of the found-footage film genre was that it allowed the viewer just a little space to believe that something impossible may have finally been captured on film. The lackluster feel of many recent entries in the genre is not just due to unimaginative scripts or uninspired direction, it’s that we have lost that original naivete, we know for certain before we watch that we are seeing a fiction, no matter how hard we try, we know all the techniques and have seen most of the tricks. So I set The Blair Witch Project as an endpoint and looked backward, because even though it’s not the first, there isn’t much horror found-footage that precedes it: Cannibal Holocaust (1980), two Guinea Pig films – Devil’s Experiment and Flower of Flesh and Blood (both 1985), The McPherson Tape (1989), and, less than a year before The Blair Witch Project, The Last Broadcast (1998). The list seems shockingly short when compared to the number of found-footage movies that came afterward and are still coming.

I came to The Last Broadcast with very little information, I remembered it came out around Blair Witch and I remembered something about a lawsuit between the filmmakers over the story. As mentioned before, The Last Broadcast actually came out about ten months before the Blair Witch and it turned out there never was an actual lawsuit, it looks more like the makers of Broadcast were unlucky enough to be caught in the shadow of the Blair juggernaut and were upset that their similarly framed film was so relatively overlooked, but it was never actually claimed that the ideas were stolen and watching these two very different movies, there really is no argument that there could have been. In fact, The Last Broadcast has quietly made millions in revenue through the years on an estimated $900 budget, minuscule even compared to Blair Witch’s legendarily small budget. Other than these details, related not so much to Broadcast as its relationship with the Blair Witch franchise, I knew nothing going in.

After watching it, I was mostly left with criticisms and questions about its execution as a film. Much of the acting was amateurish, the flow of the story was rough beyond the inherent roughness of found footage, and there were creative decisions made, especially in the last act of the film, that seemed completely wrong. But…the more I thought about the problems I had with the movie, the more I realized they were the same things that make it so necessary for understanding the found-footage genre. The Last Broadcast is raw, unsophisticated, and rattles around like a box full of empty film canisters, but by being all those things it shows us a map of what makes the genre, at its best, so damn fascinating.

Broadcast was directed by Stefan Avalos and Lance Weiler, both of whom act in the film as the co-hosts of the fictional public access show, “Fact or Fiction.” Neither director is the product of film schools, Avalos is actually trained as a classical musician, but both learned the craft journeyman style, working on commercials and music videos as assistants and technical operators before taking the helm of their own picture. Faced with a lack of money, equipment, and talent, they made the choice to incorporate their lack of resources into the film itself. That seems like an easy or obvious choice now, but in 1998, the only examples they would have had were listed above and included two, obscure and sometimes suppressed Japanese horror films (Guinea Pig movies), a micro-budget alien horror whose stock was almost destroyed by a factory fire and had no wide release until 2018 (McPherson Tape), and an (at the time) 18-year-old Italian horror, that had also been banned in several countries and only received limited release in America (Cannibal Holocaust). There was no successful predecessor at the time to recommend a found-footage approach to them other than necessity.

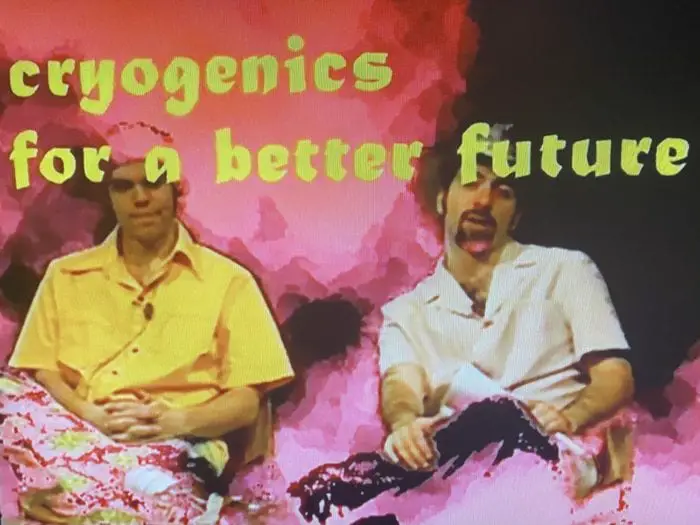

The Last Broadcast takes a broad approach to the media it incorporates. Unlike Blair Witch, nominally filmed by one film camera and one Hi8 camcorder, Broadcast uses several different hand-held cameras, police interrogation footage, computer screens, VHS tape, public access TV footage, court trial transcripts, news media broadcasts, and talking-head interviews. It’s constructed in a manner more reminiscent of a true-crime television episode than a pile of tape found buried in a basement. Considering one of the directors, Weiler, went on to become a ground-breaker in trans-media productions incorporating multiple different media forms into single projects, the diversity of mediums is not surprising and gives the directors more room to both stretch their story as well as a greater ability to cover the rough edges of their narrative. As with many other meta-fiction elements within the film, the range of media involved is incorporated as a plot point in the film. As they begin their broadcast from the Jersey pine barrens at the beginning of their search for the Jersey Devil, Avalos and Weiler in their characters as “Fact or Fiction” hosts, Johnny Avkast and Locus Wheeler respectively, announce with obvious pride that their show is the first to be simultaneous “internet broadcast, cable, ham radio—all live, all real.” Or as the Orwellian voice of the narrator/filmmaker notes: “The media has become the story.”

Broadcast constantly calls attention to its own flaws, in ways that can be seen in some instances as a natural result of the story, in other instances it almost feels like a defensive mechanism, like they want to let us know they know that this isn’t an exceptionally polished film. As we are shown a brief montage of convincing-looking public access footage for “Fact or Fiction,” the narrator notes the show was “short on production value, talent and execution, [and] it maintained a following of youth probably more amused by its kitsch value than anything else.” Later, the professional editor hired by the prosecution in the murder trial appraises the footage he worked on from the pine barrens: “This was badly shot but at least it was out in the woods. It was different.” This brings up a key advantage of found-footage, at least early on before the proliferation of tiny, professional-level cameras, the genre could sacrifice quality for immediacy and access to areas that traditionally required massive budgets and crews for access. Again, the narrator as a character in the movie lets us know as he drives out to the pine barrens that he is “using this video camera just as a matter of convenience. Using film out here would prove to be logistically too difficult.”

Our attention is drawn again and again to the idea of truth and its relationship to storytelling. It would be fair to say that outside the immediate story within a story of murder in the woods, the three most important characters are each editor of rough film material that comprise roughly the three sections of the film. Firstly, we have the prosecution editor mentioned earlier, apparently nicknamed by media within the film as the “Killer Cutter.” It becomes very clear he is involved in unknowingly crafting a false narrative based on the footage available from the eponymous last broadcast of the public access show, he is building a story provided by the prosecution with the purpose of convicting someone they believe is the murderer but we learn is not.

Later we are introduced to Michelle Monarch, who titles herself a “magnetic media data recovery specialist” and is charged with assembling the box of loose tape mysteriously dropped on the narrator’s doorstep as he makes his movie. We get several shots of Michelle intently snipping and piecing together loose inches and feet of tape, looking for the truth and her interview segments make clear she is set as a counterpoint to the killer cutter, she is only interested in finding out the truth she believes is hidden in the tape, the final footage from the night of the last broadcast. It is possible these two dueling editors are the fact and fiction referred to by the name of the public access show.

Book-ending these two narratives and the film as a whole is the footage ostensibly assembled and shot by the narrator-documentarian. He tells us repeatedly that all he is interested in is the truth, that he is convinced the wrong man was convicted for these murders and that he is determined to find the true killer. Strange forces are suggested as the identity of the real culprit is teased through small sections of rough videotape, specifically at several points throughout the movie, we see glimpses of what looks like a body of some sort laid out. It’s blurry and the color is washed out but we get the distinct impression of a large-headed figure laid out on a table, the first thing called to mind is alien autopsy footage, another application of found-footage techniques that have created confusions about its reality in the culture at large. It’s never clear whether this is an intentional red herring in a movie that features a search for a cryptozoological creature, and it’s not even clear on what level this misdirect occurs—is it inserted by the directors of The Last Broadcast or is it inserted by the documentarian inside the film. Are we supposed to believe the Jersey Devil is possibly aliens? Did the makers of “Fact or Fiction” think that? It’s never really addressed or mentioned but the suggestion of deeper mystery ends up playing fairly well in this world.

It’s the revelation of the murderer, which for me was the most frustrating aspect of The Last Broadcast. Once Michelle’s reconstruction of the movie’s literal found-footage is complete, the identity is revealed and the filming-style moves abruptly from the diegetic found-footage film to a traditional omniscient filming style. Suddenly, we see the action on the screen from shots and angles that do not belong to a camera in the world of the narrative, the editing style switches to a typical quick-cut style as a struggle ensues and we are even shown images from the perspective of the characters point-of-view. There is no warning or preparation for this whiplash switch. It’s clear that the directors moved to this style to let us in on the bigger picture that has been hidden by the tight framing of camera shots and the editing process, we have only been shown a part of the picture and the timeline presented has been distorted in its presentation.

Watching this final segment, I couldn’t help comparing it to all the films that came after it and all the ways the directors could have shown us this additional information without pulling us out of the world they’ve created. I couldn’t see the reason for their choice, what did they gain by going that route? If anything, by switching to traditional film storytelling, their lack of production value was laid bare, the tricks that worked inside a found-footage world, just look bad when given to us in the usual manner. It’s the difference between Paranormal Activity as a found-footage collection of security camera footage and The Amityville Horror filmed with security cameras. One of those can make sense, the other just becomes a cheaply shot film.

It wasn’t until I talked it over with my wife, showed her the moment of the switch and we discussed it, that she suggested that maybe they just didn’t know how to do it any other way. It all clicked. That’s exactly what happened. And its exactly what makes The Last Broadcast so exciting and interesting to watch. Like I said earlier, these were journeymen filmmakers. They knew there were certain ways films were shot, they knew how to frame, they knew how to block out a shot and they had the creativity and passion to find a way to make the movie they wanted in an effective manner on a shoe-string budget. But those final minutes of the movie needed something a little more. I have seen countless movies where a hand-held camera is dropped and falls to the floor but keeps running as the action continues in the background. A trick as simple as that could have preserved the structural integrity of the movie, you only have to think of the last shot of Blair Witch, with Josh standing in the corner, Heather is hit over the head, and the camera falls to the ground.

But it just never occurred to the directors here. Experimenting with the technology, combining media in a new manner, a trans-media production—is a different skill set than understanding the rules of film composition well enough to dare enough to break them. Avalos and Weiler didn’t have those skills and they had not one movie that they could readily look to in order to learn those tricks. And once I understood that—the last few minutes of Broadcast became the most illuminating section. This was the moment that the borderline showed. We see on the screen the very limits of found-footage theory as it stood prior to the Blair Witch revolution and that is a thrilling place to be and makes The Last Broadcast worth the time of, not just horror fans, but anyone interested in the development of a genre and film theory overall.

Looking for more horror film genre analysis? We’ve to you:

“Don’t Get Your Hopes Up: The Evolution Of The Fake Happy Ending In Horror”

“Hair as Body Horror in Exte: Hair Extensions”

“Silent Films and Modern Characters”