Gentrification is not a new idea. It was once called urban development before that name grew increasingly unjust. It was political pandering to appease sheltered suburbanites while making it seem like help is coming to urban neighborhoods. Director Josh Atkinson delivers an atmosphere of pure paranoia panic in Displaced.

In recent years, gentrification has gotten more persistent. Higher-income tenants move into drastically changed urban neighborhoods, forcing many residents to relocate. Unable to sustain their former lifestyles, vacating tenants uproot their entire lives to settle in places they can afford. The result is living with the fear of having it happen all over again. Now, what if your new neighbors want to evict you from your body instead?

Displaced tells the story of Nate (Philip Jayoni), a young reclusive social worker. He is great with kids that are in the foster system, but terribly awkward when it comes to anyone else. Nate seeks to piece together the events of his own traumatic youth when his parents led an extremist cult. His memories from his time in the Temple of the Jackal cult haunt his nightmares. Through years of recovery, Nate continues to struggle with what is real and what isn’t.

Nate’s parents didn’t fare so well and never made it out from the police raid that disbanded the cult. Now, Nate maintains a low profile in his Grandmother’s (Hope Harley) Brooklyn apartment building. Desperately afraid of the cult’s resurgence, he rigs cameras throughout the other tenants’ apartments, bringing a new layer to the idea of “fear thy neighbor.”

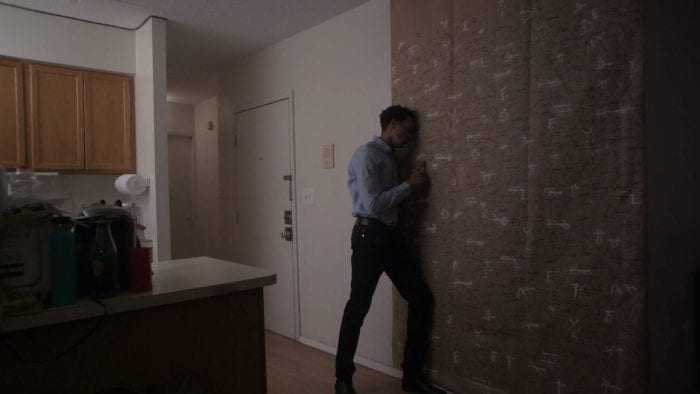

The worlds Atkinson builds for Nate, both inside his apartment and inside his head, are superb. The viewer starts to feel how trapped Nate is through seeing the hieroglyphic-like wallpaper that adorns his apartment and witnessing his caginess toward pursuing relationships. The security camera aspect challenges the audience with Nate’s awareness of his own paranoia.

When a vacancy in the building suddenly arises, wholesome Midwesterners Heather and Lucas (Megan Fitzgerald and Josh Atkinson) jump at the opportunity. They secure the space before the sign can even go up. Nate’s suspicions of the building’s first white occupants begin when Lucas sleepwalks through the building. The result finds Lucas meandering around Nate’s apartment. As Nate tries to escort him out, Lucas grabs a knife. Standing over a cowering Nate, Lucas utters a line Nate hasn’t heard since he was a child.

Atkinson puts an interesting spin on Displaced by introducing Lucas and Heather to an urban neighborhood. It makes for a fascinating scenario, like if the family in Get Out came to meet their daughter’s boyfriend instead of the reverse. It’s supremely entertaining watching Lucas and Heather psychologically tangle Nate’s carefully arranged world. Their methodical steps further muddy the viewer’s ability to decipher if Nate still has his wits about him.

Nate begins to break. Every time he thinks he has proof that his neighbors are the psychotic cultists he thinks they are, his evidence isn’t exactly as he recalls it. Trying to steer through his memories of what’s true while not being able to trust his eyes proves increasingly difficult. Nate loses the help of his friend, Jasmine (ShaQuanna Williams), who begins to see the more manic side of him. As isolative as he feels in his life prior to the arrival of his neighbors, he becomes more outgoing. He seeks more answers after the only person he feels a connection with is gone.

It’s a fantastic sense of doubt Atkinson creates for his viewers, subtly playing with Nate’s fragile sense of sanity in a near Lovecraftian manner. Paranoia, insecurity, and fear drive him to overcome his solitary lifestyle and find answers. This conflicts with how his neighbors already perceive Nate to be. The odds are always being stacked against Nate no matter what he does or how he acts. This makes for a fun and anxious environment for viewers watching Jayoni work.

What’s more unique to Displaced may be Atkinson’s personal history with cults. His father, a Christian all his life, changed his views after finalizing his divorce. The sect then sought to recruit Josh as well. In a statement on the Displaced website, Josh writes, “Incrementally he fell in more and more with a sect of fundamentalist Christians who attempted to separate me from the rest of my family. Specifically, they tried to convince me that my mother and sister were in league with the devil for divorcing my father.” He continues,

I haven’t spoken to my dad in seventeen years and I don’t know if he is, in fact, still alive. But I have thought a great deal about his mental state and developed a certain kind of sympathy for him. Through writing and directing this film, I’ve come to understand how isolated someone would have to feel in order to join a cult. I think my father felt profoundly alone.

Inspired by the works of Krzystof Kieślowski, Displaced contains many of Kieślowski’s recurring themes of paranoia and voyeurism in urban environments. There’s a strong Rosemary’s Baby vibe on the film, as well. As his neighbors get closer to bringing the cult’s leader back through Nate, the comparisons become greater.

I thoroughly enjoyed Displaced. It is a bit rough around the edges, but this is Atkinson’s directorial debut. And what he carves out here is a fun, creepy, and satisfying urban horror story. The cast is also relatively new. They go through bouts of stiffness, but it’s not often, and they remain charming. Plus, the story itself is solid and told with well-paced tension throughout. Atkinson has a distinct idea of what is important throughout Displaced, moving the movie along with lucidity and precision.

Displaced will have its world premiere at this year’s all-virtual Salem Horrorfest during its first weekend beginning October 2nd.