I was lucky enough to be able to attend the 8th annual Brooklyn Horror Film Festival this past week. Unfortunately, due to my work schedule, I was only able to make a small handful of films, so had to choose carefully. My coverage on this site tends to trend a bit more negative than I’d like it to (I love horror; I’m just a picky b*tch!) so I went with the four films I felt had the most potential to really blow me away. And I have to give myself a pat on the back for accuracy because, out of the four, three were total bangers. So let’s get into it! From worst to best, here’s what The Brooklyn Horror Film Festival had to offer this year (that I was able to catch—fingers crossed I can see the rest of them when they get a wider release.)

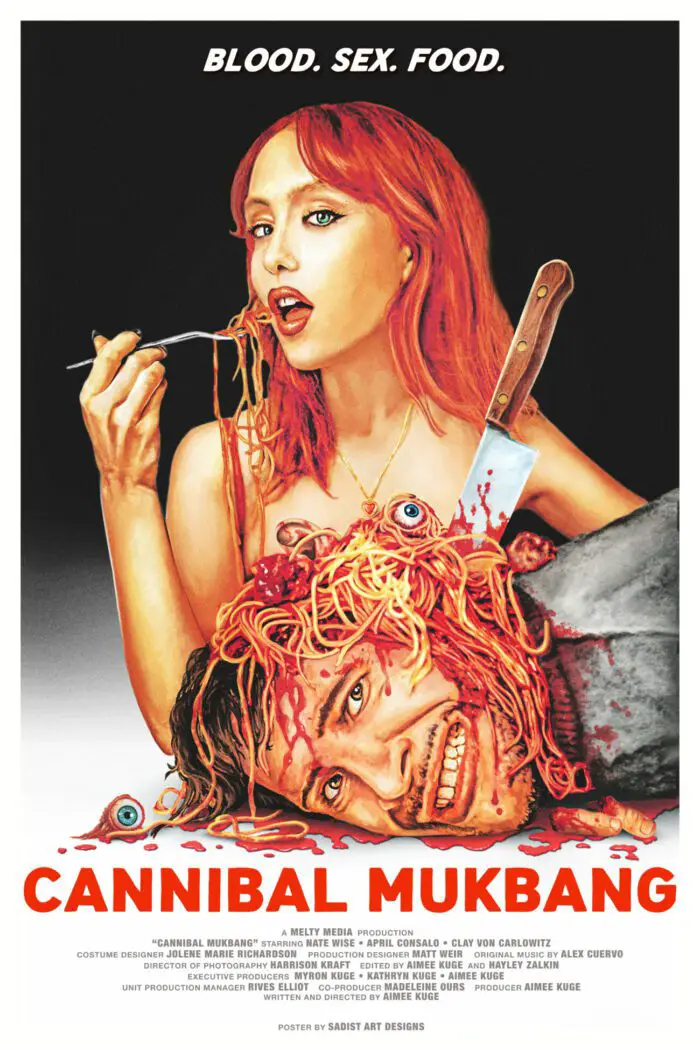

Miss: Cannibal Mukbang

I wanted to love this one. And to be fair, it seems that many did, so feel free to ignore me and go check it out for yourself. While everything about this film by director Aimee Kuge should’ve been a hit for me (cannibalism! practical effects! weird, niche subcultures!), it unfortunately just never quite came together as a coherent whole.

The overall story proceeds as follows: Nate Wise’s Mark is a closed-off orphan schlub who spends his considerable free time watching mukbang videos. Other than his relationship with his Patrick Bateman-lite brother, this is all we’ll ever need to know about him. One night, he runs into Ash (April Consalo), a mukbang content creator, at a convenience store and the rest is history. History here meaning that they fall in love and Ash introduces Mark to the world of, you guessed it, cannibal mukbang.

And I hate to break it to you, but even that brief summary paragraph made the movie sound more fun than it is. It wants so badly to be fun. I wanted so badly for it to be fun. But it just isn’t. The performers vacillate wildly (and not particularly intentionally) between chewing up scenery and playing it CW-sincere. At first, I thought Consalo was making some sort of commentary on the manic pixie dream-girl archetype, but no, that’s just who the character is. Nate Wise fares a bit better, but that could also be chalked up to his character having a touch more complexity. The performances aren’t aided by the oddly flaccid writing. You can hear the pauses where you’re supposed to laugh, but the feeling doesn’t come organically. Even the story itself seems half-baked and sloppy, which I could’ve lived with if there was any real risk-taking or ambition within the sloppiness. It’s clear that the team behind Cannibal Mukbang was aiming to create a new camp classic, but the film has its tongue so firmly glued to its cheek that it’s impossible to taste any real flavor throughout the experience. I wanted the film to stand on its own, but instead, it seemed to be more interested in alluding to other, better films.

While watching Cannibal Mukbang, I was reminded a bit of Anna Biller’s The Love Witch, a film that has a similar interest in cinematic nostalgia, focus on style over substance, and lazy pseudo-feminist politic. But while The Love Witch is elevated by Biller’s singular, lunatic vision and well-researched creative ingenuity, Cannibal Mukbang can barely commit to itself. I wanted more cannibal! More mukbang! More sex! More blood! More food! Instead, I left the theater still hungry.

Catch: Stopmotion

If you’re looking for a movie that commits to its material, this nasty little piece of work sure does the trick. Stopmotion, prolific short-film director Robert Morgan’s first full-length feature, follows stop-motion animator Ella Blake’s descent into madness following the death of her mother. We are first introduced to the pair of women as Ella helps animate one of her mother’s films. Her mother, we learn, is a well-known stop-motion animator (who, notably, refers to Ella by the pet-name of “poppet”), and Ella dreams of following in her footsteps. But instead, she’s stuck moving armature limbs a couple of millimeters to the right or left under her mother’s stern command. Or, as her mother more concisely and cruelly puts it: “I have the ideas and you have the hands.”

Then, after her mother’s sudden collapse and subsequent passing, Ella is free to explore her own creative vision for the first time. Or is she? Before she even has a chance to grieve, Ella is having visions of a young girl who visits her in her studio every day to tell her the next part of a strange story about a girl hiding in the woods from “the ash man.” After each night of troubled, nightmare-plagued sleep, Ella wakes to find that she has animated the new piece of the story. Even more disturbing are the increasingly gory materials Ella sources to create “poppets” of her own.

Before I discuss what made this film so special, I first want to address where it stumbles. For a character-driven movie, Stopmotion seems disappointingly uninterested in its characters. Aisling Franciosi draws on all of her considerable talents to bring Ella to life within a story that, ironically enough, uses its characters as mere puppets to further the plot. We get only the barest details about who Ella is, what her relationship with her mother was like, what drives her, what scares her, etc. On a meta-textual level, this is an interesting move, but it also took away from my immersion into the world of the film.

Still, the strengths of the movie more than makeup for this misstep. Morgan is a remarkably skilled filmmaker and visual artist, and the stop-motion scenes here are absolutely stunning. How refreshing to experience a story about a talented artist of some kind in which the work the character produces is actually as shockingly brilliant as it’s supposed to be. Additionally, while the story itself is not without its missteps, the writing and pacing are both tight, spare, and unflinching. Also unflinching is the level of gore and true body horror here, though without over-doing it. It’s a strange and effective combination that led me to actually fully gag in the middle of the theater, which I can honestly say hasn’t happened to me before!

This is one of those movies that might be easily lost in the streaming-service shuffle, so I strongly encourage you to check it out when it becomes available. In the meantime, take a peek at some of Robert Morgan’s terrifying shorts!

Must-See: Red Rooms (Les Chambres Rouges)

“Catch this movie when it comes out!” is not nearly commanding enough to capture how strongly I urge you all to watch Red Rooms as soon as you possibly can. Masterfully directed by Canadian filmmaker Pascal Plante, this film is a meticulously crafted exploration of voyeurism and the solipsistic depravity that drives true crime obsessives.

This is one of those films that are genuinely challenging to capture in writing, at least if I attempt to outline what made it so effective, thrilling, and thought-provoking. If I say that the film opens with a long, continuous take of the opening arguments in a murder trial, I fail to capture the way the camera rubbernecks around the space, watching everyone in the room in an uncannily human way before finally settling in on our central figure, Kelly Ann. If I say that Juliette Gariépy as Kelly Ann is captivating and chilling, I’m still unable to fully convey how, at key moments, her wide-eyed, inscrutable stare is used like a jump scare. If I say that every moment of visual or aural nastiness here is perfectly crafted and positioned within the film to provoke maximum dread and terror, then I don’t even feel like anyone will understand what I mean until they go watch the film for themselves.

All of this is to say, I would kill to read a long-form piece written by someone much smarter than me about the brilliant ways Plante uses camera movement and sound in this film to both shock and implicate his audience. What I can do is give you a brief overview of the film so you know what you’re getting into:

A man is on trial for the murder of three young girls. Or, rather, for kidnapping, torturing, filming, and murdering three young girls and subsequently distributing these snuff films over the dark web in exchange for considerable sums of money. Ludovic Chevalier, the man in question, is a mousy, unassuming figure who sits cuffed in a plastic box throughout the court proceedings. He fidgets and looks down at his hands while the prosecution outlines the vile, heinous acts he has allegedly committed against three teenaged girls. Due to a couple of technical hitches (the perpetrator’s face is mostly hidden in the videos, Chevalier hasn’t been living beyond his means), there is a small amount of doubt that the prosecution can successfully make its case, but the abundance of evidence against Chevalier leaves little doubt that he is the murderer in question and Plante seems disinterested in provoking any sort of whodunit interrogation.

Two women (and the film’s audience) stayed glued to the court proceedings. Both steely Kelly Ann and fragile, outspoken Clementine come before dawn each day to wait outside the courtroom in order to secure themselves seats. Though the women don’t know each other, these unique circumstances spark a kind of tentative friendship between them.

Each has an interest in Chevalier, but that’s where their similarities seem to end. Intense, aloof Kelly Ann is a model and professional online poker player who lives a highly controlled and isolated existence in her expensive apartment where she spends much of her time perusing the hidden corners of the internet. Her fascination with Chevalier is unclear and is one of the driving mysteries of the film. We know less about Clementine, though it’s clear that she’s young and vulnerable and more or less homeless. Clementine will tell anyone with ears why she’s so interested in the Chevalier case. She knows he’s innocent, she tells court reporters and talk show hosts. His eyes are so kind, she insists; she’s sure it wasn’t him.

The relationship between these two women and their tangled, yet separate, motivations surrounding the trial drives the story until it doesn’t. Apologies for being vague but, given how effectively Plante harnesses real shock and dread in this film, any spoiler would be a disservice. When you go and see this film, which I could not urge you more strongly to do, I hope you leave thinking—not about who committed which crime and why—but about the charged emptiness of looking, the dangers of being seen, and what it means to be caught staring.

New Obsession: She is Conann (Conann)

After seeing Red Rooms, I was certain no other film in the festival could top it. I would describe Red Rooms as a “perfect movie,” meaning that there was nothing—from individual pieces of dialogue to sound design to cinematography and beyond—that I wished had been done differently. But if Red Rooms is a perfect movie, She is Conann is a transcendent one. When this stunning, singular jewel of a film ended, I stayed in my seat and willed the world built inside of it to continue. Though it’s popular nowadays to claim that no movie should ever run longer than 90 minutes, I could’ve watched this one for hours if not days on end.

Mandico’s vision of Conan the Barbarian begins with Conann as a captive of Sanja and her crew of barbarian women. Sanja is also flanked by hell-dog Rainer, our impish, melancholy narrator for the duration of the film. Rainer takes a liking to Conann and, with Rainer’s help, Conann breaks free of her captivity and takes brutal, bloody vengeance on her captors. Only Sanja escapes. Before Conann can enjoy her new freedom, she’s visited by a future version of herself.

“Look how tall you’ve become, how handsome,” 25-year-old Conann gloats to 15-year-old Conann before the two embrace and Conann’s future slays her present to take her place.

The pattern repeats, with each new iteration of Conann killing her predecessor and bringing the audience to a new world. Each time, she’s ten years older, but the world around her moves at a different pace. Together, with Conann and Rainer (and occasionally Sanja), we travel from the Bronze Age to the Bronx, from the world of the dead to the distant future. While Rainer stays the same, watching and photographing and interfering when necessary, Conann perpetually transforms. We get Conann the Lover, Conann the Fascist, and even Conann the Artist. Each timeline is a new type of visual feast (and sometimes a literal feast.) Despite working on a mico-budget, everyone who contributed to the vision that is She is Conann skillfully crafted a film in which every frame is absolutely stunning.

I had been curious about where Mandico was going by making Conann a woman and ended up surprised and delighted when I realized that, rather than standing on its own as some sort of discrete commentary of gender roles, the gender-swapping was a byproduct of the movie’s overall queer sensibility. Gender, sexuality, and embodiment are all played with in thorny, interesting ways throughout the film. I was fascinated by the figure of Rainer (stand-out performer Elina Löwensohn in effectively uncanny facial prosthetics), who one review I read called “the sole male figure in the film.” When I read this description, I laughed, almost delighted by the way it failed to capture the transgressive nature of this character: a man who is not a man because he is a dog who is also a queer woman and, perhaps above all, is a metaphor. Even “hell-dog he/him lesbian” is too pat a description to give to this slippery, wildly charismatic character. (Though it’s definitely how I’ve described him when discussing the movie casually with friends.)

Going into the film, I had no idea what was in store for me, though I suspected it would be something quite different from the comics I loved as a kid. My suspicion proved to be both right on target and slightly off-base. While Bertrand Mandico’s glittering, grimy vision of battle-weary barbarian dykes passionately slamming cars into each other, ritual cannibalism in the name of art, and lovelorn demon dogs inciting chaos and then sticking around to photograph every gory detail bears little resemblance to the muscle-bound he-men and bikini-clad vixens of the illustrations I remember from childhood, something of a spiritual through-line exists between the two. In both iterations of the story, violence, and physicality are brought to nearly ludicrous extremes while at the same time being treated with total seriousness. No tension exists between the two; holding both absurdity and true pathos together, She is Conann transcends camp and pushes towards the sublime.

Thank you to the Brooklyn Horror Film Festival for putting on such a fantastic show and inviting me along to experience it! And thanks to all of you for reading. If you managed to catch any of the films that I missed, please let me know what you think.