As a new writer at Horror Obsessive, I’m doing my best to make a good impression. So, what do I pitch when first given an opportunity to do so? A takedown of one of the most beloved film franchises on this site. I may be a fool, and I may be shooting myself in the foot, but I also know that I’m right: A Quiet Place sucks ass and John Krasinski is my personal enemy.

But Saskia, you might say, the monsters were so cool! The story was so touching! And don’t we all love Jim from The Office? The first one I’ll give you, the second I’ll take issue with, and the third I’ll deny outright. F*ck Jim, f*ck John Krasinski, and f*ck his sh*tty little post-apocalyptic white homesteader fantasy.

Before I dig in, let me start with a disclaimer: I have no patience for reactionary horror. To me, horror is the realm of freaks, queers, monsters, and perverts—the outcasts and the overlooked. I proudly count myself among their ranks. While other genres may seek to soothe and affirm, horror offers something much more difficult, yet leagues more rewarding. Truly great horror serves to upend traditional values. A Quiet Place upholds them.

Save the monsters themselves, whom I love and cherish, there are no freaks to be found in this film. Instead, we open with a prototypical family comprising a mother, a father, and their three—oops, make that two—children. (Would it be too glib to count them as 2.5?) The father, named Lee and embodied by John Krasinski with a truly remarkable amount of self-seriousness, is such an uncreative masculine fantasy of fatherhood it’s almost comical. He broods, he hunts, he dispenses his highly sought-after approval at opportune moments, he pushes women and children out of the way when danger’s near, he tinkers with machinery, he’s engrossed in some sort of Very Important Research, he has a beard…He’s also, as the movie makes pains to remind us as often as possible, very sad. So very, very sad. Heavy is the hand that holds the World’s Best Dad mug.

His wife Evelyn, played by Emily Blunt doing her best impression of a TikTok tradwife influencer, seems to be in charge of every household task that falls outside of Lee’s masculine purview. She cooks, she cleans, she homeschools the children…in short, women’s work. She’s patient and nurturing; she never complains, choosing instead to bear her many burdens with a sort of angelic feminine grace. She’s also sad, but her sadness, the film suggests, is of a slightly less important strain than Lee’s sadness. Much more important is the fact that she’s pregnant—actually, most important. No, truly, while Lee’s character is filled out at least a little by a complex relationship with his daughter and lingering guilt over the death of his son, Evelyn’s pregnancy is the only thing of substance that we’ll ever learn about her.

The youngest of the children is dispatched so quickly that we don’t really get a sense of his character. No matter; he’s only there to give a hint of emotional stakes to the proceedings. Marcus, the older son, fits neatly into the archetype that so many boys his age fill in genre movies—curious, sensitive, and a little annoying. His blunders occasionally drive the plot forward and there are moments in which he offers up bits of naïf wisdom, yet he has no discernible motivations or interests of his own. Instead, he usually serves as a point of contrast for his father or sister.

His sister Regan has a bit more heft to her character, but only just. I will give John Krasinski props for seeking out a Deaf actress to play Regan, Lee and Evelyn’s Deaf daughter. But he doesn’t really deserve them. Casting Deaf and disabled actors to play Deaf and disabled characters is ground floor-level work when it comes to issues of representation. And despite Millicent Simmons’s best efforts, Regan is nearly as underdeveloped as the rest of her family, serving more as a narrative device than as a person. Like her brother, Regan doesn’t seem to have any interests or much of a personality. Unlike Marcus, she does have clear motivations, however limited they may be. The guilt she carries over her role in the death of her brother and her search for her father’s approval drive the emotional arc of the story, just as her deafness serves to support the central conceit of the film and provide a solution for the central problem. She may be a cipher, but she’s carrying the plot on her back.

So, what of this plot? I think a case could be made that there are two main stories told in A Quiet Place, each with a different—though equally insidious—message. The first story, which drives the action of the film, concerns the parents’ attempts to keep their children safe in an unsafe world.

Here is where we see some of the most ham-fisted examples of the reactionary themes present in the film. The bucolic homesteading lifestyle that the family lives is both highly idealized and filled with details that belie its regressive underpinnings. There are a beautiful set of canning shelves in the basement stocked with at least a year’s worth of preserves and hand-woven fishing baskets set in the river and teeming with fresh catches (one guess as to which parent is responsible for which). But there are also security cameras monitoring every inch of the property and rifles on hand should anyone need to stand their ground. (In this fantasy, the need for these familiar trappings of safety seems to supersede a need for more practical interventions like a thoroughly soundproofed house.) Each member of the family has a gendered role in this fantasy: the mother maintains the home and pumps out children, the daughter supports the mother and cares for her siblings, the father protects and provides for the household, and the son is apprenticed by his father in the ways of masculine leadership.

Though the movie’s family-values-tinged lens is entirely uncritical of these roles, there are many moments throughout the film that hint at questionable (at best) dynamics within the family unit. Only the son is seen attending homeschooling classes, and no mention is made of the daughter’s absence. In a subsequent scene, the father forces his unwilling son to go fishing with him while rebuffing his daughter when she expresses an interest in going instead. “I need you to help your mother,” he tells her. When the son later asks his father why he didn’t allow the daughter to come, the two end up bonding over a discussion about guilt and forgiveness, but Lee never answers his son’s question. And yet, the film insists over and over again, both explicitly and implicitly, that these are the ideal parents, the ideal family. The white nuclear family is a haven of safety and love, A Quiet Place tells us; it’s the outside world we should be afraid of.

“We have to protect them,” the parents say to each other, over and over and over again in regards to their children. In the world of the film, the most important role a parent (particularly a father) can play is that of protector. But what does this look like in action? Well, Lee and Evelyn bring their children along on perilous errands into the outside world, constantly lose track of their whereabouts, and push them to take on responsibilities that put them under direct threat of violence. So…not any of those things. Instead, “protecting” the children means constant monitoring for threats outside of the home. It means teaching the son how to take care of himself and his family while ignoring the daughter. It means working tirelessly to repair the daughter’s cochlear implant because, within the logic of the film, she couldn’t possibly be safe (or a contributing member of the household) without it. It means dramatic acts of self-sacrifice.

Most of all, though, it means protecting Evelyn’s unborn child, who is not really a child yet, does not have any of the complexities of a real child, and is, therefore, the ideal child to protect. While their two real, live children run around getting attacked by monsters and nearly suffocating to death in grain silos, Lee and Evelyn focus all their efforts on ensuring the safe delivery of their almost-child. You can probably see where I’m going with this. It’s almost too obvious to spell out. But still, it’s astounding to watch a blockbuster film made within this decade by a run-of-the-mill good Hollywood liberal broadcast such a glaringly pro-life message. I was particularly struck by the care taken to highlight Evelyn’s noble, silent suffering in service of the birth of her child. The most heroic thing a woman can do, the film suggests, is to martyr herself for the sake of the unborn.

The second story, which drives the “heart” of the film, is that of the fraught father-daughter relationship between Lee and Regan. Regan, who had an indirect hand in the death of her younger brother, is plagued by guilt and fear that her father blames her for the loss of his son. Strangely, she has no such fears about her mother—though perhaps this is not so strange, as everyone in the family seems to value Lee’s approval over all else. Lee, for his part, seems vaguely guilty that he’s having this effect on his daughter, though it’s never explained why he hasn’t spoken to her about it in the year since it happened nor made any attempt to rebuild their relationship prior to the events of the movie.

Instead, he tinkers with her cochlear implants as if this alone is enough to show her his love. After all, men aren’t good with emotions and communication, right? They have to show by doing, not saying. Meanwhile, Regan wanders aimlessly around the property, largely ignored by her parents now that her lack of access to the hearing world renders her, in their eyes, too vulnerable to be of much use to the family. The only scene between the two of them before the climax involves Lee showing Regan the work he’s doing on her implant. When she won’t accept his attempt to bond over his efforts to “fix” her, he slumps off, resigned. If she won’t accept his help, then what else can he do to show her he cares for her?

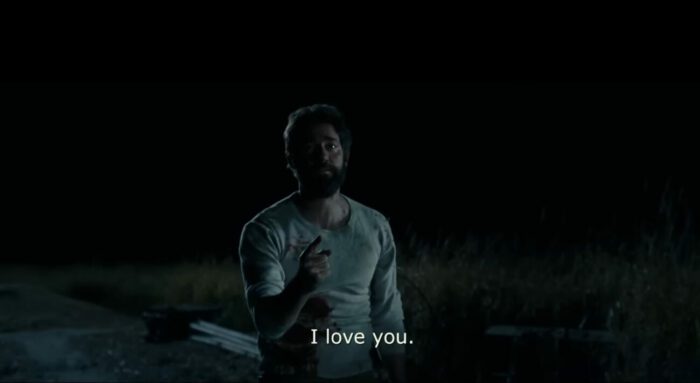

After Lee rejects Regan’s plea to be included in the fishing trip, he has a joyful bonding experience with his son that highlights the contrast in his relationships with his two children. With his son, Lee is confident and chipper. Surrounded by the noise of the river and a nearby waterfall, they show visible relief as they yell and laugh and speak aloud, joining together in the world of sounds, a world Regan can’t access. Marcus asks Lee why Regan couldn’t come and Lee doesn’t answer. Marcus then follows up by asking if Lee blames Regan for “what happened.” After a long pause, Lee says he doesn’t. Marcus tells Lee that Regan blames herself for what happened and that, if Lee loves her, he should tell her that. So, he does. At the very end of the movie. As he lets one of the monsters maul him to death in a heroic gesture to save his children.

This moment serves as the emotional climax of the film. The action itself climaxes with Regan’s realization that her faulty cochlear implant emits a noise that disorients and harms the monsters, rendering her Deafness a secret weapon instead of a disadvantage. These hollow platitudes (“Tell your kids you love them”; “Your differences are your superpowers”) hardly serve as satisfying takeaways from a film riddled with lazy writing, thin characterization, and sketchy politics. If the film contained even a hint of a critical lens, perhaps something could be made of this story. But no. Lee is the ideal father. Evelyn is the ideal mother. And together, they are the ideal white nuclear family, nobly fighting against outsiders who seek to destroy the dream they’ve created together.

At a pivotal moment in The Quiet Place, Evelyn turns to Lee and asks, “Who are we if we can’t protect them?” And the answer seems to be no one. Or rather, anyone you want them to be. They’re just the vaguest ideas of people, of what people should be, serving to protect their traditional values against a manufactured threat. For fans of this film, I urge you to take a second look at it. Ask yourselves, does the titular quiet serve any real purpose, or does it only exist because the filmmaker had nothing to say?

What a terrible article. This woke writer is an ### and like it or not, if such a situation like the movie happened then everyone would happily take up their biological gender roles. Men are stronger and better at outdoor things. Which leaves the indoor and “tradwife” things to the females. Grow up.

I like how there’s a related articles by JP Nunez that takes a polar opposite stance.

I’ll passive-aggressively point out that this take is, popular usage aside, quite reactionary. It’s also not really all that unpopular. People have been noticing the conservative undertones from the start, to the point where Krasinski issued a statement saying that he didn’t intend said undertones.

Horror is a spot for the outcasts, but more subtly so, and not exclusively by any means. It’s also been more about the dichotomy of an introverted slasher heroine vs. the mutilated rambunctious sluts (does this site have censors?) rather than the more overtly politicized messages showing up more often since the 2010s. This is something I generally despise, whether they have a conservative or liberal leaning. I guess I’m annoyed by anyone that’s not Verhoeven.

What bothers me more than any such ideas is that it is not practical considering their situation. The film starts off pragmatically in the pharmacy, only to underplay the character’s strengths. Despite this, the film does end with the girl being the one who finds a way to kill the monster while the boy is holding the baby, so perhaps you could say that the message of traditional gender roles is subverted at that point?

I’m only just watching the second film at this point of writing, so I don’t know how these controversies play into it.

I don’t know what convinced me to be the only comment on some article I stumbled upon, but here’s my disjointed contribution.