I’ll admit it right off the bat: I am outrageously biased towards the Fear Street movies. The series was my gateway drug into the world of horror; some of my fondest childhood memories were devouring volume after volume at…arguably too young of an age, eagerly diving into its pulpy world of teen romance, obsession, seduction, betrayal, and murder. So when I first heard that there were not one, but three movies coming to Netflix, I immediately began counting down the days before they dropped on Netflix, ready for three weeks of big, dumb summer fun.

While I certainly got my fill of big dumb fun, what surprised me was what a profound story it wound up telling over the course of the three films. The series lets us know from the very beginning that it plans on challenging our idea of what a Fear Street movie would look like, from the opening scene of a woman buying a copy of The Wrong Number (written here by friendly-sounding Robert Lawrence instead of sinisterly named R.L. Stine) and dismissing it as “trash” and “lowbrow horror” to Sam turning out to be extremely different from the tall, dark-haired, moody and aggressive football player I had immediately pictured upon hearing that Deena was having problems with her ex. The Fear Street trilogy goes on to tackle a lot of big themes that I would have never really expected to see, from LGBTQ+ identity to generational trauma, and—to me at least—handles them much better than they really had any business doing.

But what ultimately ties all of these themes together is that they’re all about stories. The ones we’re told, the ones we tell ourselves, and most crucially, the people who tell those stories and how they can be used to keep existing power structures alive—and unquestioned.

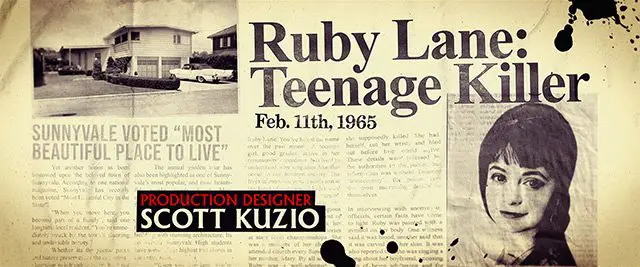

As we see in 1994 and 1978, the story of Shadyside is by and large defined by Sarah Fier. The legend surrounding her and the curse she placed on the town is central to their identity, both in how they see themselves and how the rest of the world sees them. The town has clearly attempted to accept and come to peace with this part of their history (Shadyside Witches, anyone?) but we can clearly see the negative impact that living in “Killer Capital, U.S.A.” has had on the people who live there.

There is an overwhelming sense of hopelessness that hangs over the youth of Shadyside, one that we can see span across generations. Even Deena, who doesn’t believe in the curse of Sarah Fier, feels that there is something about living in Shadyside that defines her life and the possibilities in it, telling Sam that all she could see for herself was a future of “A night shift, a day shift, and a million empty beer cans. Just like my dad. No way out.”

It’s thrown into sharp relief whenever Sunnyvale gets involved. As we see throughout those opening credits, Sunnyvale isn’t just free of violent crime, just about every part of life is better over there than it is in Shadyside. The football team always wins, it’s consistently called one of the best places in America to live, even the Great Depression wasn’t as hard on them as it was on their neighbors. We see the effects of this prosperity reflected in the teenagers of Sunnyvale, who have very clearly grown up with a sense that they are somehow better than the people of Shadyside. As one of the Sunnyvale teens puts it at the memorial held for the first 1994 victims, “What we should do is light a fuse and burn down Shittyside…I said it ain’t a tragedy when it happens every week. It’s a joke.” In 1978, the Sunnyvale campers even go so far as to attempt a gruesome reenactment of Sarah Fier’s hanging with Ziggy in her place.

It isn’t just that Shadyside has a history of their citizens suddenly turning into killers, it’s that they are repeatedly made out to be somehow deserving of all the horrors that they repeatedly face. “Shadysiders seem to have no desire to better themselves,” we hear an unknown voice tell us in 1994’s opening credits, one of many that echo this narrative, reinforcing it in both the minds of Shadyside’s citizens and the minds of people everywhere. How many people over the years were likely turned down for a job or a scholarship or a relationship just because they were from Shadyside?

And then we reach 1666 and everything gets turned inside out.

1666 plays out as a fairly straightforward take on Wicker Man/Midsommar style folk horror, focusing on the horrors of mob mentality and how easily people will turn on the most vulnerable members of a community when things go wrong or they’re being driven by fear. What’s compelling about the film is the efficiency and almost glee with which it takes a sledgehammer to its own lore, showing us just what a far cry from the truth the story of Sarah Fier is. Just about everything that both the audience and the characters have been told about Sarah Fier turns out to either be an outright lie or a fact that has been stretched and distorted beyond recognition.

Yes, in hindsight, it’s pretty obvious what the truth behind Shadyside’s origins and ongoing struggles are: that Sarah Fier was innocent, and it was, in fact, Solomon Goode who had made a deal with the devil, promising that he would give a soul every few years in exchange for ensuring the prosperity of their family. But it’s still a bold direction for the series to take, directly confronting the lore that the people of Shadyside have accepted as fact and showing us just how far from the truth a narrative can become when it is presented to us from a single, unchallenged point of view.

Earlier in the summer, I read a book by author and poet Clint Smith, called How The Word Is Passed. In it, he visits six places across the U.S. with ties to both the history and the ongoing narrative of slavery, and how each one of those sites attempts to push a particular aspect of that larger narrative, whether accurate or not. After attending a gathering held by the Sons of the Confederates, a group largely composed of people who have direct family ties to the Confederacy, and hearing how they try to frame the story of the Confederacy, Smith makes a telling observation on the often personal nature of how history is told: “So much of the story we tell about history is really the story we tell about ourselves. It is the story of our mothers and fathers and their mothers and fathers, as far back as our lineages will take us…But just because someone tells you a story doesn’t make that story true.”

It’s no accident that the story of Shadyside’s origins is told the way that it is. Sarah Fier being blamed for the curse on Shadyside is central to how the Goode family tells its own story to the people of Sunnyvale, to the outside world, and to themselves. History, as we are often told, is written by the victors, and the reveal recontextualizes much of what we’ve seen to this point and shines a light on who has the power to define a narrative and how that power can be used to benefit a particular group at the expense of another.

Through the attitudes that we see held by both Nick and Solomon, we get a fairly clear picture of how the men of the Goode family see themselves and the narrative that they pass down from generation to generation: that they are right to wield the unnatural, evil power that Solomon unearthed, that they are entitled to that power and all the benefits it provides, and that it is their duty as head of the family to continue the cycle of death that ensures their continued prosperity.

One of the most sinister visuals of the series comes when we see generation after generation of the Goodes offering up the literal blood and flesh of Shadysiders to ensure that their own wealth and status remain intact. Even when we see Nick showing what appears to be genuine unease with being the head of the Goode family back in 1978, he nonetheless gives Tommy’s name in 1978 and Ryan and Sam’s names in 1994. Another way that people try to excuse or defend horrors in the past is that it is part of their heritage or family legacy, and there clearly seems to be a sense of that present in the Goodes’ continuation of the cycle of violence that plagues Shadyside.

“One person every few years seems a small price to pay,” Solomon tells Sarah after she discovers the truth, without a thought given to the 12 people Cyrus Miller murdered after he was given to the devil. Centuries later, Nick seethes to Deena that “[Solomon] extended his hand to the darkness for my family, for me! For 300 years we’ve cultivated it, we’ve sacrificed for it!,” casting himself and his ancestors without a hint of irony given that the ’sacrifice’ in question was them selling Shadysiders to the devil while not appearing to have needed to give up anything tangible for themselves.

While the wealth of the family themselves and the prosperity of Sunnyvale play a large part in the narrative surrounding the Goodes, even more crucial is how they are repeatedly found in positions of authority where they can easily shape the narratives of both Shadyside and Sunnyvale. In his role as county sheriff, we see how Nick Goode helps to reinforce and continue those narratives, casting Simon and Kate as “druggies who went on a rampage” and attempting to minimize and erase the narratives of people that get too close to the truth that would threaten the narrative of the Goode family.

He even tells Deena as much, saying “You’re gonna be famous! Shadyside’s newest piece of shit makes the front page! Local [lesbian] slays girlfriend, friends, brother…and they’re gonna give me a fucking medal.” The influence and power to shape the narrative that he wields means that the contempt he and his family hold for the people of Shadyside is, in turn, reflected in the citizens of Sunnyvale and the hostility they show to their neighbors. Their influence even extends to the land itself. As we see in 1994’s opening credits, the Goodes bought the land that Camp Nightwing was built on after the 1978 killings and constructed the Shadyside Mall there, not only leaving the tree where Sarah Fier had been hung in place but turning it into the centerpiece of the mall—a grim reminder of just how many signs of past horrors physically remain in our lives, whether seen or unseen.

The power of narratives is something we can see in our world on what has become a near-daily basis. How often do we still see LGBTQ+ people not only be cast as “deviant” or “unnatural” or “immoral” but blamed for everything from natural disasters to the spread of coronavirus? How often do we still see people of color be told that they just have to work harder and that their own perceived moral failings are responsible for the struggles they face instead of the centuries-old power structures that ensure that they have little to no opportunity for success? And on the opposite side of the coin, how often do we still see white men who have committed violent crimes framed as “misunderstood”? How often do we hear that those with wealth and influence are “elite” or “self-made“, as though they’ve somehow worked harder or were smarter or are otherwise better to have gotten to where they were, instead of acknowledging any of the external factors that so often determine the course that our lives take?

Stories are everywhere in our world. They not only define how we see ourselves, but how we see other people. But these stories are often presented to us in a way that fits a particular narrative, only giving us a portion of the truth, or hiding the truth entirely, and the only solution to this is to challenge the narrative and seek the truth beyond what is presented to us. We may not have the benefit of “blood magic allowing us to see the unfiltered truth through the eyes of those involved,” but there are written accounts we have access to that can give us a point of view that is normally minimized. In my chosen field of study, there’s been a growing movement over the last few years to “expand the canon” of readings and authors being taught to include more women writers and writers of color.

Even throughout the story, we see examples of how people can challenge the narrative when they know it to be untrue or incomplete. Josh tells his chat room friends about who Kate and Simon really were when he sees them accepting the “official” narrative without question. Ziggy defends Nurse Lane from the people who dismiss her as having “gone crazy just like her daughter did.” Deena refuses to accept that there is nothing that can be done to save Sam and digs further and further past the narrative she’s been presented with, eventually leading her to find the previously untold side of Sarah Fier’s story.

In its final moments, Fear Street points us in a hopeful direction. As Sarah tells Solomon, having falsely confessed for the crime of witchcraft to save Hannah’s life: “The truth will come out. Maybe not today, and maybe not tomorrow, but it will. The truth shall be your curse.” As soon as the Goode family’s deal with the devil is broken, a fatal car accident occurs just outside of Sheriff Goode’s home, and a news report detailing Nick’s involvement in the Shadyside killings states that “all is no longer well in Sunnyvale.” These false narratives the film tells us, are extraordinarily fragile, only existing as long as people are willing to believe in them without question—and start to crumble the minute someone starts to genuinely seek the truth beyond the story they’ve been told. Truth, the story tells us, takes time. Sometimes, it has to come out one person at a time. But it is inevitable—and in the end, it sets us free.