Trigger warning: This article contains references to murder, including the murder of animals and children.

And we are back for the next in the series of our look into the myths, legends, and inspirations behind some of the most interesting and influential J-Horror (Japanese Horror) films and some others from the Asian horror movie scene during the late 1990s and early 2000s. This month, we take a special look at Ju-On: The Grudge.

Ju-On: The Series That Started It All

Ju-On, also known as Curse of Grudge, is a Japanese American horror film franchise that includes 13 films and one television series, created by Takashi Shimizu. In 1998 Shimizu would create two short films, Katasumi and 4444444444 while attending the Film School of Tokyo. He would study under Kiyoshi Kurosawa, a legendary horror director with a 15-year career by this point in time, and with his help, Shimizu would bring the Ju-On project to life.

The series is centered on a curse that emanates from a house in Nerima, Tokyo, Japan where a horrendously violent crime took place. Within the mythology of the films, when someone dies with a deep and uncontrollable rage, a curse is created, affecting not just the location of the crime but anyone who enters the building. This also extends to anyone who comes in contact with an already cursed individual, allowing it to spread like a virus.

What is Ju-On: The Grudge?

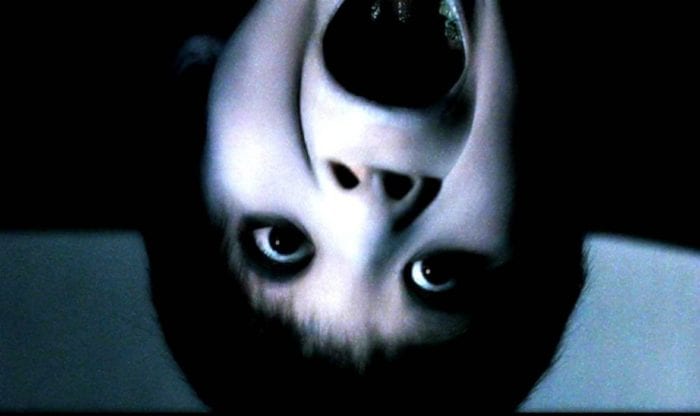

In the third installment in the series, released in October 2002 during the Screamfest Film Festival, we meet social worker Rika who is asked to visit a house in Nerima, Tokyo to check in on an elderly lady named Sachie. The story is told in a non-linear narrative, making the viewer piece together what is truly happening while the true horror of the tale isn’t revealed until the end. The film is bookended by Rika entering the house for the first time and for the last time—everything in between is told in a deconstructed narrative, jumping back and forth over a five-year period. But this story is about Rika and her journey from being a social worker to becoming a cursed spirit herself.

The curse in Ju-On arises when, in a jealous rage, Tekeo Seaki murders his wife Kayako, their son Toshio and the family cat. His family becomes vengeful ghosts, haunting the house and all who enter it, the ghost of Kayako is the one to murder her husband, trapping them all in the house forever.

Ju-On: The Grudge was loved by critics but did receive comparisons to Ringu/The Ring, even though both these films are vastly different in story and visual stylings. It inspired an American franchise simply called The Grudge.

Yotsuya Kaidan and Its Influence on Ju-On: The Grudge

The film has loose connections to the Japanese tale of Yotsuya Kaida which is one of the most influential and widely adapted folk stories in Japan. Over 30 films are influenced by the tale of Oiwa and Tamiya Lemon. The story was written in 1825 with the original title of Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan as a kabuki play by Tsuruya Nanboku IV.

As with any adaptation, the details of this tale have been altered over time from its original telling, with subplots and the cast of characters expanding. The story still keeps its key themes of the exchange of power, social unrest, the repression of women, revenge, jealousy, and murder. The story follows Tamiya lemon and his descent into madness and the chaos around him as he goes on a rampage of murder to get what he wants. We also follow Naosuke, a man obsessed with a prostitute he meets at a brothel, as well as the story of two sisters Oiwa, the wife of lemon, and Osode, the aforementioned prostitute who is married to another man, known as Yomoshichi.

The story is full of intrigue and complicated relationships, with lemon’s wife being disfigured and eventually dying at the hands of the Itô family in an attempt to marry Oume, the head of the family’s granddaughter, off to him. Lemon is haunted by the ghost of his deceased wife, Oiwa, who tricks him into murdering Oume, her grandfather, and the rest of the household in revenge. Naosuke, after killing a man and continuing to pursue Osode, who he marries, finds out after a returning Yomoshichi accuses Oume of adultery leading to her death, that in fact Naosuke’s new wife, Oume, is his younger sister.

This is written in a letter from Oume to Naosuke, who is so filled with shame over this discovery that he takes his own life. In the last act of the play, Lemon has completely descended into madness with Oiwa’s ghost still haunting him. Yomoshichi, full of vengeance and compassion over this man’s plight, kills him, leaving Yomoshichi as the last surviving member of the core five characters.

This story also has a historical context. It combines two real-life murders in order to create a truly authentic and terrifying ghost story. The first was that of two servants who murdered their masters. These two incidents took place separately, with both being caught and then executed on the same day. The second true-life crime is that of a samurai who has his concubine and servant, who he discovers is having an affair, nailed to a wooden board and thrown into the Kanda River. You can see in the original story how these influenced the writing of the original Kabuki play.

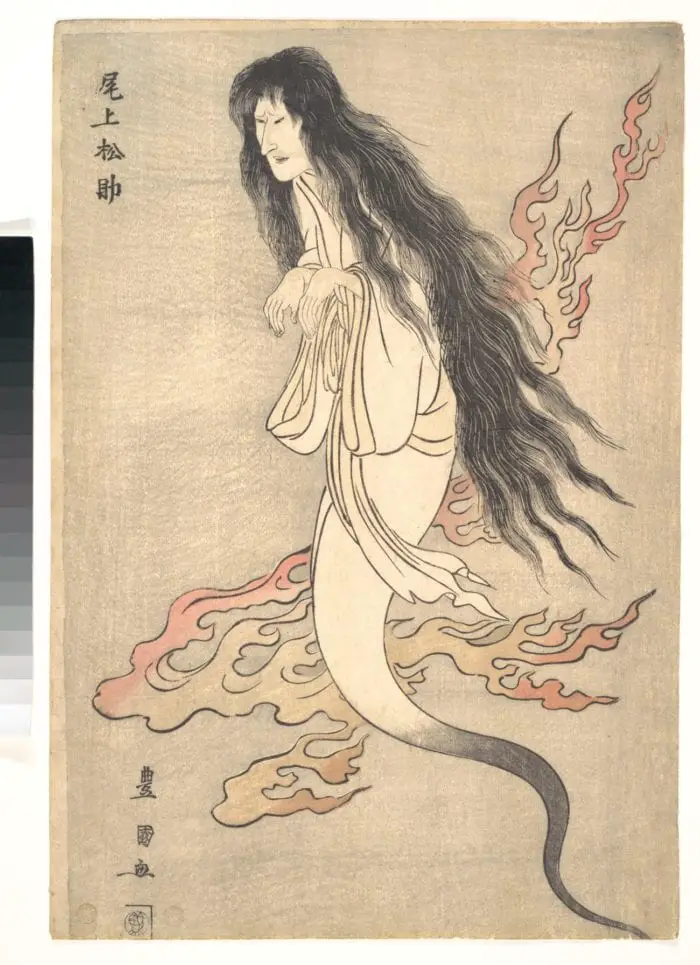

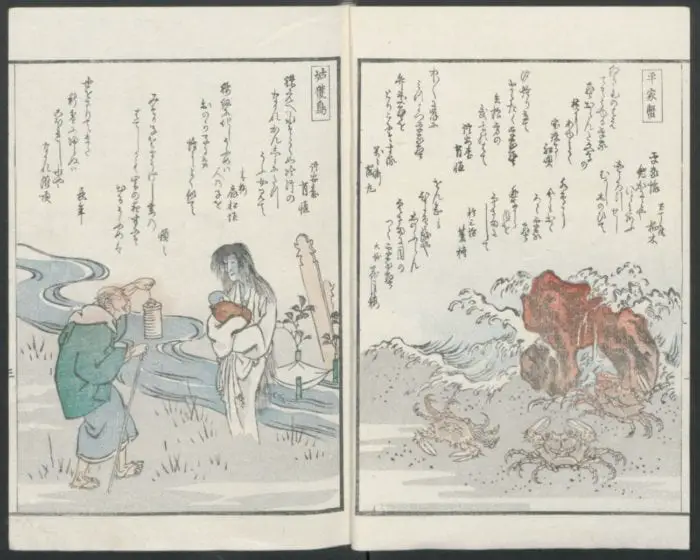

The story didn’t just become popular in kabuki theatres all over Japan, but also in ukiyo-e art. For those who don’t know ukiyo-e is a traditional Japanese art form where artists create woodblock prints and paintings mainly depicting women, flora, fauna, and erotica, becoming popular between the 17th and 19th centuries. One of the first depictions of Yotsuya Kaidan in art is by Shunkosai Hokushu, who produced The Ghost of Oiwa.

Hauntings & Exorcisms in Japanese Culture

Hauntings and exorcisms are prevalent in Japanese culture and ghost stories, focusing on Yurei who fall under the Obake, which means to change, in this instance from the natural realm to the supernatural.

While yūrei have a specific time period for their hauntings and purpose when they strike, between the hours of 2:00 AM–2:30 AM, the Obake can strike at any time, while not being bound to a specific place and can roam how they wish. That Obake have no purpose behind their hauntings is a terrifying idea. While yūrei are driven by revenge or completing unfinished business, Obake have no such ideas or limitations.

The ghosts in Ju-On: The Grudge are earthbound spirits that do not seek to fulfill any exact purpose. They are considered a rare type of spirit, fuyūrei, who are bound to specific situations and places, haunting not just the location but the people who enter it. Ju-On: The Grudge is a clear example of this along with Okiku at the well of Himeji Castle.

Famous hauntings tend to go hand in hand with folklore in Japan. This includes the previously mentioned well at Himeji Castle, which is said to be haunted by two ghosts, Okiki and Aokigahara, but there are two others I will be focusing on.

The first haunting is of Aokigahara, known to westerners as the suicide forest, which is a forest located at the northwest base of Mount Fuji. There are many different tales and legends relating to ghosts, daemons, yūrei, and yōkai roaming the forest and preying on innocent travelers. By the 19th century, it had become commonplace for poorer families to abandon children and the elderly in Aokigahara, resulting in even more stories being told about the forest. Its dark past has come to light in recent years, with its reputation for being the third most popular suicide spot in the world being a topic of discussion.

The second is the hauntings by Oiwa, who is classed as an onryō. It’s said that she will bring vengeance on any actress who portrays her on stage or screen. She, along with Okiku and Otsuya, make up the San O-Yūrei, who are the three most well-known characters in Japanese folklore as their stories have been the most popular and widely circulated via word of mouth, stage productions, and into the modern-day with film and television.

So how do we exorcise a Yurei? We ask this question as we delve into a franchise here where the hauntings don’t seem to ever end. Very much like Ringu, Ju-On as a series seems to have a never-ending collection of disappearances and deaths; the spirits always seem to win before an exorcism takes place. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t practices and ways to exorcise a spirit in Japanese culture.

As you might suspect, the easiest way to exorcise a yūrei is to help them fulfill their purpose, be that revenge or justice. This will normally allow the spirit to leave his plane of existence. The family of the victim or spirit are traditionally those who will help the spirit move on, be that by enacting revenge, helping the ghost consummate its passion/love, or by finding the remains and performing the correct burial rituals. These methods will not work on an onryō as their emotions are particularly strong and will stay in this realm to cause as much destruction as they can.

Colours and their Meaning in Asian Horror Tales

White is the most well-known colour used in Asian horror films, from the ashy white/grey of a ghost’s complexion to the long white outfits that are traditionally adorned by these characters. Every aspect of why white is used to represent ghosts and death can be traced back to the Edo period and its use in kabuki, art, and funeral traditions. The white signifies how in kabuki a white kimono would often be used in the costumes of ghosts, which directly relates to the burial Kimono used in the Edo period. White is also the colour of purity in the Shinto traditions of Japan and is often reserved for only priests and the dead.

Black hair is traditionally long and disheveled when it comes to Japanese folk tales. This look is carried over from Kabuki theatre productions that included ghost stories. This isn’t the only place that this comes from; women used to grow their hair long, wearing it pinned up most of the time. The only time a woman would let their hair down was for funerals and burials. This tradition surrounding death has seeped into the very fabric of ghost stories and their visual language.

Blue, green, and purple are used normally in kabuki but have been used in legends of Yūrei. They are ghostly flames that are produced by the spirit known as will-o’-the-wisps, or Hitodama in Japanese. These eerie colours bring a more menacing look to the spirits and enhance the supernatural elements of these stories.

Look out for the rest of the series coming soon, where I look at other Japanese horror films including Pulse, Dark Water, and Uzumaki. I also will look at the South Korean film, A Tale of Two Sisters, the Thai film, Shutter, and the Hong Kong production, The Eye.