Trigger warning: This article contains a mention of rape and murder.

In the first in a new series, I will take a look into the myths, legends, and inspirations behind some of the most interesting and influential J-Horror (Japanese Horror) films and some others from the Asian horror movie market during the late 1990s and early 2000s. This month, we take a special look at The Ring aka Ringu, a highly influential film that has even inspired me within my work as a photographer.

You can look at the differences between the book and film at Bam In Real Life.

Ringu (リング): The Book that Started It All

The Ring was originally a Japanese mystery horror novel by Koji Suzuki, which was first published in 1991 and became the first in a trilogy followed by 1995’s Spiral and 1998’s Loop. The novel has inspired many films and TV series through the years.

There have been four film adaptations—Kanzenban (1995), Ring (1998), The Ring Virus (1999), and The Ring (2002); two manga versions—Ring (1996) released by Kouhirou Nagai and Ring: Volume 2 (1999) released by Misao Inagaki; two audio dramas—Ring (1996) and Ring (2015); and a TV series, Ring: The Final Chapter (1999).

The book follows a Tokyo newspaper reporter, Kazuyuki Asakawa, whose obsession with UFOs and ghosts leads him to investigate the deaths of four teenagers from a cursed video tape, and he is the uncle of one of the victims. He enlists the help of a philosophy professor, Ryuji Takayama, who claims to be a rapist (at the very least, he jokes about it) and is profiled as a psychopath. This character has a much more profound roll in the two sequels, Spiral and Loop.

They uncover the tragic tale of Sadako Yamamura, an intersex person who vanished 30 years before after being raped and thrown into a well by a doctor at the sanatorium where her father was being treated. Sadako also has psychic powers and was the person behind the cursed videotape.

Ring (リング, Ringu): The Film that Popularised J-Horror

Ring is a Japanese horror film released in 1998 and directed by Hideo Nakata, based on the novel of the same name by Koji Suzuki (1991). The film follows the plot of the book, with some notable exceptions, such as TV reporter Reiko Asakawa played by Nanako Matsushima who is investigating a mysterious videotape that kills the viewer after seven days.

The film took nine months to film and produce, and it released at the same time as its sequel film, Spiral. It became a huge box office success in Japan, being critically acclaimed. It also began a whole franchise, popularised the J-Horror genre all across the world, and began the Western obsession with remaking Japanese horror films.

Its influence can be seen even in Western films. Coinciding with the release of The Blair Witch Project, it caused a shift from the slasher sub-genre to a more cerebral look at the horror genre, which allows much of the real horror to exist in the viewer’s mind.

The Legend Behind Ring

The film has a huge focus between the clashing of traditional Japanese folklore and expectations with the modern times in which we live. Film critic Colette Balmain has said, “In the figure of Sadako, Ring [utilises the] vengeful yūrei archetype of conventional Japanese horror.” She argues how this traditional Japanese figure is expressed via a videotape which “embodies contemporary anxieties, in that it is technology through which the repressed past reasserts itself.”

A yūrei is a figure of Japanese folklore that can be likened to the Western idea of a ghost or even the women in white myths. They are spirits barred from a peaceful afterlife and therefore must roam the earth. In traditional Japanese culture, all humans have spirit/soul called a reikon, which leaves the body after a person dies and waits to join its ancestors, which happens after a funeral and post-funeral rite being performed. They will then become the protector of their living family, returning every August during the Obon Festival to receive thanks—this is similar to other beliefs all around the world.

In the event of a sudden or violent death where the proper rites are not preformed, or the death is tied to powerful emotions, the reikon will transform into a yūrei. They will stay on this earthly plain until the missing rites are preformed or the emotional conflict tying them here is resolved.Like with any ghost or yūrei, there are many different types, but we will look specifically at the onryō, which is a vengeful ghost that comes back to this plane of existence to exact revenge on those who wronged them while alive. This is the kind of spirit found in Ringu.

In Japanese folklore, an onryō is a vengeful spirit. Very much like the western idea of a vengeful spirit or poltergeist, an onryō is capable of causing harm in the living world, being able to even kill its enemies, or those it perceives to have harmed them in their living life. It is unknown when the belief in Onryō first came about, but it is believed to have originated in the Eighth Century. These spirts, in addition to being able to harm their enemies, also are said to be able to cause natural disasters.

What does an onryō or yūrei look like? And why?

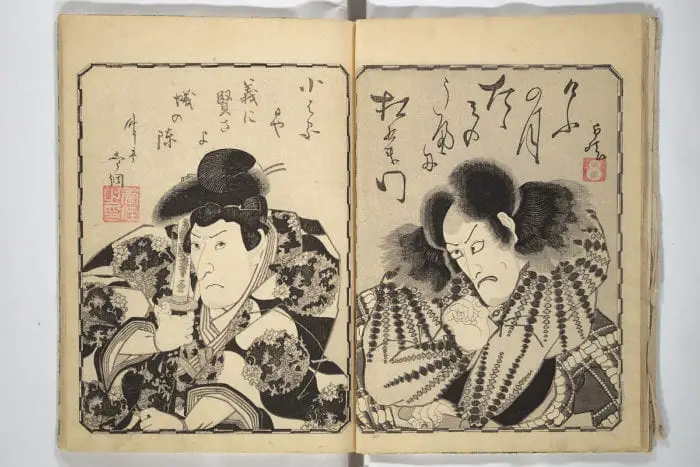

In local Japanese tradition, an onryō or yūrei didn’t have a set appearance, but with the rise of Kabuki during the Edo period, a costume was needed to represent the character on stage. This has now grown into the typical look for a yūrei, but why are these things used?

The art of Kabuki theatre is a classical form of entertainment in Japan, telling a story through both drama and dance. It is known for its beautiful and stylised performances with outlandish costumes, makeup and masks. Izumo no Okuni formed a female dance troupe during the yearly Edo period, and thus Kabuki was born. Women preformed as a part of Kabuki up until 1629, when they were banned from preforming, allowing for the all-male productions for which it is now known. By the mid-eighteenth century, kabuki was at its height in popularity, but it is making a resurgence in Japan in the last few years, even being placed on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

To put it simply, in Kabuki, like many other forms of theatre, there needs to be a visual shorthand for the audience to know which character is which. In this case, the yūrei is represented by the actor having wild, unkempt long black hair, face makeup of white foundation, blue shadows known as ‘indigo fringe,’ while wearing a traditional burial kimono. We will explore this more in-depth when we look at The Grudge.

So how does Okiku at the well of Himeji Castle influence Ringu?

The tale of Okiku at the well of Himeji Castle heavily inspired the story of Ringu, but there are many different versions of the folk tale. The three most well-known ones are the traditional folk version, the Ningyō Jōruri version, and the Okamoto Kido version. Despite each version being slightly different, all versions tell the tale of a young female servant who dies unjustly, returning to the land of the living to hunt those who have wronged her. The folktale is as follows:

Once there was a beautiful servant named Okiku. She worked for the samurai Aoyama Tessan. Okiku often refused him when he said he was in love with her and wanted to marry her, so he tricked her into believing that she had carelessly lost one of the family’s 10 precious Delft plates. Such a crime would normally result in her death. In a frenzy, she counted and recounted the nine plates many times. However, she could not find the tenth and went to Aoyama in guilty tears. The samurai offered to overlook the matter if she finally became his lover, but again she refused. Enraged, Aoyama threw her down a well to her death. It is said that Okiku became a vengeful spirit (onryō) who tormented her murderer by counting to nine and then making a terrible shriek to represent the missing tenth plate—or perhaps she had tormented herself and was still trying to find the tenth plate but cried out in agony when she never could. In some versions of the story, this torment continued until an exorcist or neighbour shouted “ten” in a loud voice at the end of her count. Her ghost, finally relieved that someone had found the plate for her, haunted the samurai no more.

The tale first appeared in a Bunraku play titled, Banchō Sarayashiki, in July 1741. Bunraku is the tradition in Japan of puppet theatre, and the tale went on to become a successful and popular story told in Kabuki by the end of 1824. Segawa Joko III would create a one-act version of the tale in 1850, which seemed to be ahead of its time, folding very quickly due to a lack of interest and popularity. It was revived in June 1971 and did substantially better.

The character of Okiku, who inspired Sadako, has remained a popular character within Kabuki and other forms of Japanese art and performance. She has appeared in Katsushika Hokusai’s 1830 series, One Hundred Tales, while artist Ekin painted a byōbu-e, which is a folding screen decorated with paintings and calligraphy, depicting the scene where Okiku is accused by Aoyama Tessan.

In 1916, Okamoto Kido would write the most popular adaptation of Banchō Sarayashiki. This modern take on an old classic can be compared to the way Japanese horror has progressed itself from Kabuki to film. Where Kabuki has colourful costumes and makeup, the movies produced in Asia during the late 1990s and early 2000s deal with their subject matter and visuals more subtly in their retelling of old ghost stories.

You can read more Japanese folk tales from the Konjaku Monogatarishū. Look out for the rest of the series coming soon, where I look at other Japanese Horror films including Pulse, The Grudge, Dark Water and Uzumaki. I also will look at the South Korean film, A Tale of Two Sisters, the Thai film, Shutter, and the Hong Kong production, The Eye.