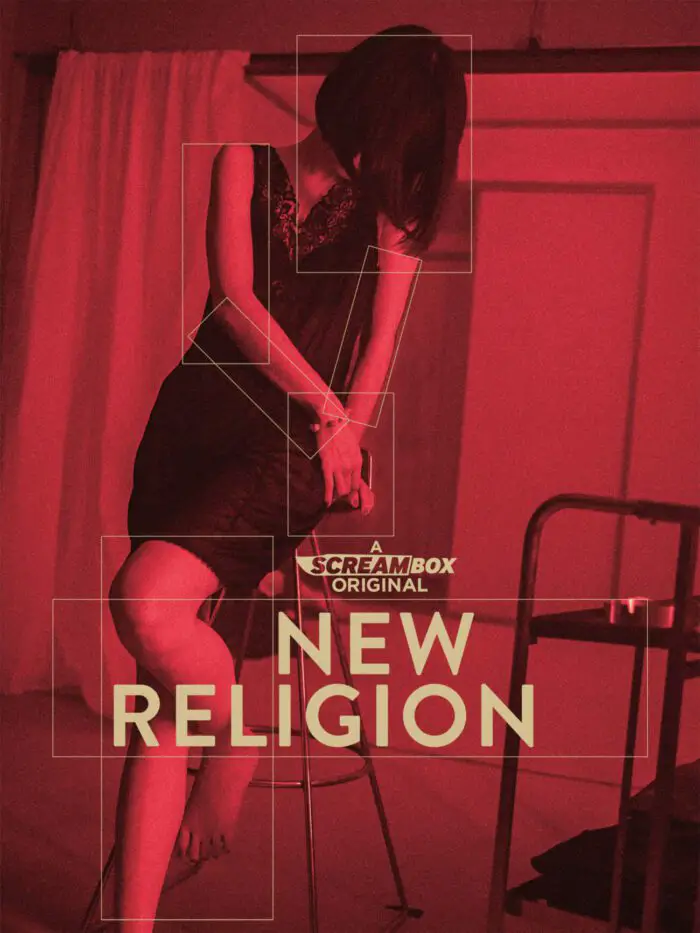

Kenshi Kondo’s feature debut, New Religion, is a strange bird. Anyone who watches Japanese Horror knows a bit of what to expect. Cinematic images: check. Slow-burn story: check. Haunting repercussions that reflect onto the audience: big check. Surrealness: giant check. Yet, it’s rare to see things blend so fluidly together, especially without having the budget to be more revealing. I can think of two films that have done it seamlessly and are near-perfect films, in my opinion, Kairo (Pulse) and Perfect Blue, which may have been a couple of the many inspirations for New Religion as well. It’s a solid start to, what I hope, is a long career for the director and one of the most fascinating films I’ve seen in a while.

New Religion immediately sets your mouth agape with the death of Miyabi’s (Kaho Seto) daughter Aoi. Kondo stages everything so peacefully, from the greenery of plants to the tableside tea Miyabi sips as she reads her book in her high-rise apartment condo. Watching her daughter water the plants on the balcony is almost relaxing. One second, Aoi is there. The next, she isn’t. It is somewhat reminiscent of the contrasting tones of the opening of Lars von Trier’s Antichrist –minus the hardcore sex. However, as the film moves three years after her daughter’s accident, Miyabi does take up a job as a sex worker. Her post-divorce live-in boyfriend (Saionji Ryuseigun) and Miyabi share a joyless one-sided love affair in the same apartment, where Miyabi is constantly reminded of and haunted by the incident.

While returning to the organization’s offices one evening, Miyabi and her valet witness her former colleague go on a murder spree in the street. Epithets about the colleague’s mental state echo through the news and permeate the office where she awaits her calls, where the mystery of her last John, Oka (Satoshi Oka), brings their own condemnations. Not long after, Miyabi begins getting calls from Oka. Despite a myriad of red flags, from entering a lightless room to having it only be lit in red, Oka requests he only wants to take a single photograph of Miyabi—a picture of her “barbarous” spine. Requests for more photos begin to come, and with every session, Miyabi begins falling into a state where she can feel and hear her daughter again. What’s real becomes indiscernible from a dream for Miyabi as her grief-spiral teeters on the verge of insanity.

A portion of the film almost feels like an anime, which is why I mentioned Perfect Blue at the start—the concept and color palettes mix, resonating with an animated sensibility. The overall patience Kondo displays also adds to that effect. And just the outright science fiction and body horror nature of the film makes New Religion feel like a graphic novel sprung to life. Or, at least, at first. As Miyabi’s transformation progresses, those elements seem to bleed into more reality-stricken visuals juxtaposed by Miyabi’s descent into madness. The deeper she slides into a dream, the more realistic the tone becomes –a feat I found rather impressive.

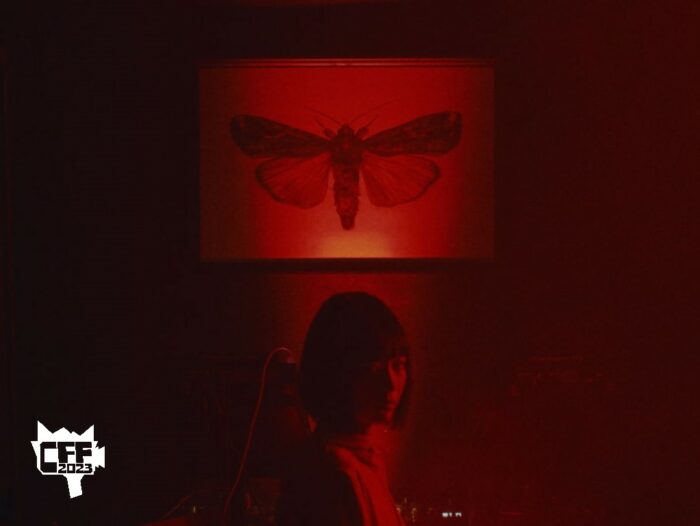

Regardless, Kondo drowns New Religion in weird through visual and aural components such as the Lynchian red room of Oka’s apartment, which is almost as symbolically limbo oriented as where Dale Cooper spends 25 years in Twin Peaks. The unnerving synth-laden score oozes unease and distress. With these elements, it’s easy for Miyabi, and the audience, to be drawn into the film. Kondo does a fantastic job of tempering the pace, filling the audience with questions as they beg to go back to Oka’s, and it only gets weirder and wilder as the movie develops. The red room feels liminal, existing in and outside of a dream, yet the memory of an unknown beach seems to be where dreams and reality meet, like the horizon line in the photograph’s distance and the promise of eternity.

The film’s title, New Religion, I had to think about. There’s the obvious moth-to-a-flame idea, where religion offers solace to grieving people by providing hope to those seeking it. It offers the possibility that what once was still is and can be again. This is exactly what Oka offers Miyabi as he continues to photograph her. Yet the testament of faith ultimately turns out negatively for Miyabi, and one wonders what that result infers.

The prominence of the moth in New Religion represents metamorphosis almost straight out of the Johnathan Demme playbook. It becomes another important piece of symbolism in the film, especially as we watch Miyabi juggle her grief, wishing only to reunite with Aoi as she shifts between states.

Next, I really must hand it to the performers. As horror fans, we don’t always get characters to connect with and feel for, and it’s particularly challenging for a film in another language to achieve that. But the cast is superb. Seto is brilliant. Oka is haunting. And Ryuseigun is emotionally empathetic. This helps the film move along when it feels like Kondo gets caught up, and the audience waits for the film to trod along a little faster. Like I said, it’s a bit of a slow roll, but the impact is pretty good once it gets going.

Grief has become the catalyst for many horror titles, especially in the elevated category. Ari Aster became a household name thanks to his titles, Hereditary and Midsommar. Still, NewReligion deserves a place in the conversation, arguing, albeit a bit more abstractly, for understanding the nature of suffering from the untimely nature of death. Post-pandemic, we forget about the people taken by the illness and then forced to resume their lives. For Miyabi, that isn’t an option. She changes everything. But getting by isn’t the same as getting over. The film ends up being mostly interpretive, but I felt it offered the idea of appropriately pointing its anger toward a careless society, though perhaps in the most extreme sense.

I genuinely felt something special with New Religion. It’s alluring, provocative, thought-provoking, and conversation-worthy. The film has been meticulously thought out and delivered in a gorgeously cinematic package. Its reminiscence to many films, from The Fly to Perfect Blue, only helps you feel more connected to it, like a dream you remember having but cannot place.

New Religion is playing as part of the Chattanooga Film Festival and will screen in person on June 24 at 9:45 PM at The Read House. Badges for virtual attendees are available and will allow you to see everything virtually. Single virtual tickets are also available. The film is also available to stream on Screambox.