The frame of The Cabin in the Woods is both there from the beginning and not fully revealed until the end.

After all, the film opens with Sitterson (Richard Jenkins) and Hadley (Bradley Whitford) discussing their plans, and while we may not know what those plans are, precisely, it is clear from the get-go that this isn’t your standard horror film—whatever is going on with them, and with Lin (Amy Acker), it is clear it is going to be important.

What are they up to? Well, we ultimately find out: it is a matter of arranging the deaths of young people to appease ancient gods. And there are other outposts around the world. Most notably, we see Japan fail, but in that same scene, we see that other countries have failed.

It is in this way that horror films across the globe are represented in relation to the central premise of The Cabin in the Woods. The film suggests that horror tropes and clichés exist for a reason. They are a part of the structure of the sacrifice in question.

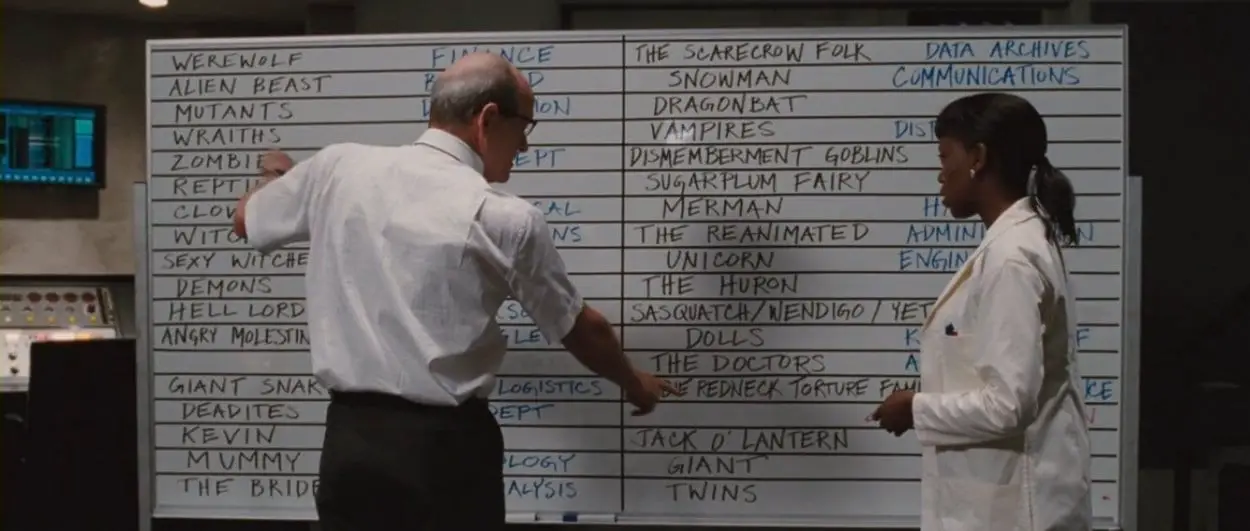

Why are there so many horror films where a group of young people goes to a cabin in the woods only to be preyed upon by a horrific…something? Many of them are so similar that their only meaningful difference is the nature of the monster. And The Cabin in the Woods drives that point home by showing the employees at the compound betting as to what the monster will be. Hadley apparently really wants it to be a Merman one of these times. It’s a minimal desire for some novelty.

Given this setup, The Cabin in the Woods plays on horror tropes all over the place. Primarily, it plays on American ones, though it nods to other cultures in the way I referenced above.

A group of young people takes off for a vacation at a cabin in the woods. On the way, they stop for gas and encounter a creepy old guy who basically says they shouldn’t go where they are going. But they do anyway. The tropes get going.

One could try to list all of the films The Cabin in the Woods references, but I’m not going to try to do that. It’s almost too general. It doesn’t matter if there are specific nods to Evil Dead or Texas Chainsaw Massacre because the film could just as well be referencing Zombeavers, which came out several years after it did.

We’ve seen this story before, or a version of it.

They all enter the cellar of the cabin and start messing with stuff, and apparently it is their choice as to what will befall them. The people back at headquarters are taking bets. And the possibility is at least recognized that they might get through this without triggering any kind of monster. But Dana (Kristen Connelly) doesn’t listen when Marty (Fran Kranz) insists that he is drawing a line and urges her not to read the Latin in the diary she has picked up. She reads it, goaded on by Curt (Chris Hemsworth) and Jules (Anna Hutchison).

These characters have increasingly started to resemble the horror stereotypes that we are familiar with from other sources. But they didn’t start out that way. Their scenes before arriving to the cabin may only provide quick characterization, but they make clear that Curt is interested in learning, for example, and that Jules is far from a dumb blonde (the hair color itself even being a recent dye job, for whatever that’s worth).

The point is that these characters are at least given some nuance at the beginning, and it is enough for it to make sense that they are friends. It is Curt who is introducing Holden (Jesse Williams) to the gang, and it seems like they share some scholarly interests. When Marty arrives, ripping on a huge collapsible coffee mug bong, it’s clear that everyone is friends with him, too.

Think about it: how many movies have we seen where the group of young people taking a trip to a cabin is composed of the following stereotypes: a jock, a ditzy blonde, a nerd, a pothead, and a virgin? Why would these people be friends when they don’t seem like friends? But yet we get this over and over again.

The Cabin in the Woods suggests an answer. It is because these are specific archetypes necessary to the sacrifice. We learn further that moves are made to push each character in the direction of their stereotype. They did something to Jules’s hair dye, for example, and have the ability to pump drugs into the cabin, etc. Things go wrong with Marty, and Dana is maybe not truly a virgin (they do the best they can with what they have to work with), but the organization behind the scenes clearly exerts an influence. Because the ancient gods must be appeased.

An interesting aspect of this, however, is the notion that the youths must be given a choice. They have to bring it upon themselves. If they’d just looked at the creepy stuff in the cellar, said, “no uh-uh” and gone back upstairs I guess they would have been fine. But of course, they didn’t do that. And to what extent is that down to the way their personalities have been influenced, and so on? Or does it rather get at something about being human and our natural propensity towards curiosity, particularly when we are young?

Dana reads the Latin and awakens a zombie family that attacks them. (Though I guess these monsters were actually being stored in the compound). There is perhaps a mild novelty to the weapons they use (is that a bear trap, or what?), but they are stereotypical zombies. The Cabin in the Woods makes a joke of this when Sitterson explains to an underling why her bet on zombies wasn’t a winner.

So this is the whole frame of The Cabin in the Woods: there is an organization that stages situations involving horror tropes and clichés. They do this around the world in various ways. It would seem each hub has different cultural touchstones, but the important thing is that one of them succeeds, or else the ancient gods are going to destroy the world. And it would seem they are up to this pretty much all of the time, whether in terms of running the current scenario or planning the next one.

So it’s just like with horror movies, but what happens here is real. If there are tropes and clichés, it is because there need to be in order to keep the gods happy. And the ancient gods demand a sacrifice.

The ancient gods are us.

Let’s think about what we enjoy when we enjoy horror movies. Don’t we enjoy the death? Isn’t there some way in which we are rooting for it, rooting for the killer in the slasher film? The virgin might live or might die—and is she a virgin…well, we do the best we can—but it doesn’t really matter either way. The point is we don’t watch these things hoping that our hero(ine) will get out of it so much as we watch in anticipation of the next kill.

And this is where The Cabin in the Woods gets to something. We want to see the fear, the suffering, and the death. There is something sublime about it. But, it is only sublime at a safe distance, like looking at a tsunami that doesn’t threaten you. The clichés and tropes of horror provide guard rails, as it were. When something comes along that lacks them, it can truly frighten and disturb us. That might mean it is novel and excellent cinema that a number of us enjoy, but the question is why there are so many cookie-cutter cabin in the woods films out there, and why we watch them.

It’s because we enjoy the familiarity. We may want some novelty like Hadley wants a Merman, but the structure provides a comfortable frame through which to watch things die from a distance.

Sitterson, Hadley, et al, then, are like producers trying to make a hit. It doesn’t matter if there is any novelty to it. It could be a remake of The Grudge or Evil Dead. The important thing is that the ancient gods are satisfied.

They aren’t in The Cabin in the Woods. Things went wrong with Marty and he didn’t die when he was supposed to. He and Dana thus make their way into the compound and figure out what is going on. The monsters are all released. There is carnage.

Hadley is killed by a Merman.

And then the Director (Sigourney Weaver) shows up to inform them of the stakes. It doesn’t matter if the virgin lives or dies, but she has to be the Final Girl. Dana, you need to kill Marty, or the world is going to end.

This creates interesting stakes because if we’re just thinking about the consequences then killing Marty would definitely seem to be the right plan. But it also feels wrong. This whole system is wrong, and perhaps it needs to be brought down even if that means taking the whole world with it. So Dana refuses, and the old gods rise to destroy everything.

Did you cheer?

It can be disturbing how many people want the actual world to end, so let’s focus on the question in the context of the film.

If the ancient gods are us (the audience), the ending of The Cabin in the Woods can be read in at least two ways. On the one hand, we might view it as the anger expressed by those who were expecting one thing and got another from a film they were anticipating. Think, perhaps, about some of the backlash against a movie like The Last Jedi. On the other hand, if we are on Dana and Marty’s side at the end of the film, it could be read as a desire for the great masses to rise up and demand better than we get from reboots, remakes, and dreck like Zombeavers.

That ambiguity is perhaps central to The Cabin in the Woods. It plays with the genre of horror, breaks it, laughs at it, critiques it, and remains within it all at the same time. Because, after all, if we do cheer for the destruction at the end of the film, isn’t that analogous to cheering for the monster?