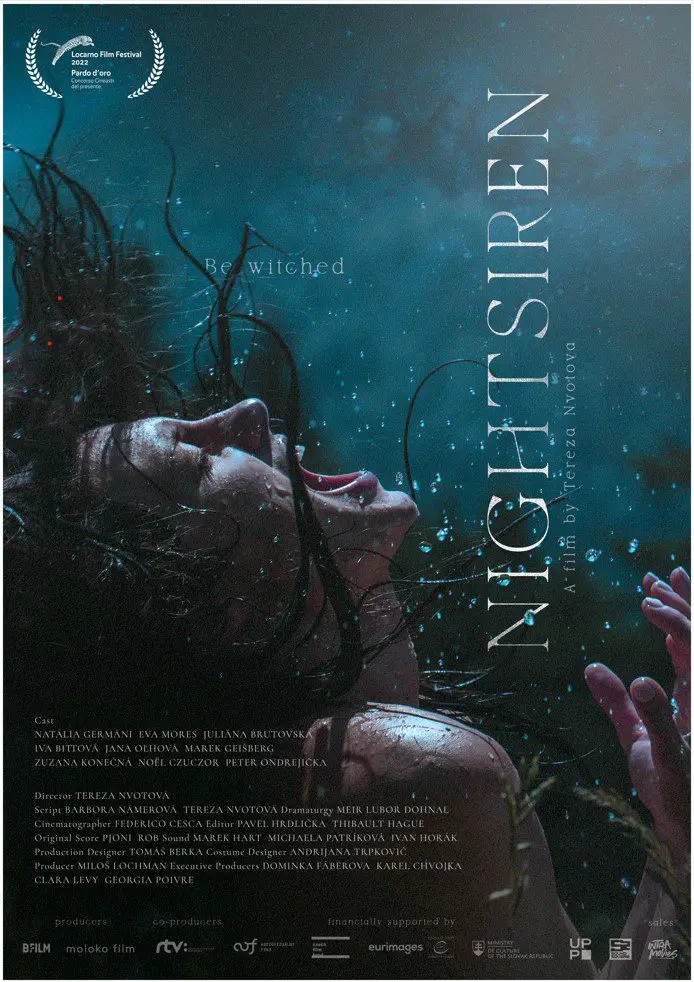

It takes no time at all for Nightsiren (Svetlonoc) to immerse you in its story. Beginning with images of a bloodied young girl in the grips of abuse, dialogue that infers something supernatural is occurring, and a jaw-dropping move that sends a toddler off a cliff, Nightsiren sucks you in. You have to admit it’s a hell of a hook. However, the best part of co-writer-director Tereza Nvotová is the film’s approach to ostracization and how non-conforming women often bear the brunt of name-calling backlash in small towns. When the movie returns from a series of images interwoven into the credits, we find a much older Šarlota, that abused young girl, returning home for the first time after those events.

Šarlota (Natalia Germani) hikes to a rundown cabin in the woods seen at the start. First, she stops by the structural outline of the house she grew up in, which has been burnt to the ground, then to another cottage nearby. Soon after she’s decided to take shelter, she is met by a rowdy bunch of young townies on ATVs and motorbikes, who seem playful at first, only to shudder in fear when Šarlota reveals her name. Quickly they scurry away as the details of a story involving Šarlota’s mother and the woman whose house she’s staying in begin to creep out.

The rumor mill doesn’t stop with just the young people in the community who grew up with the campfire tales about what happened on the hillside. When Šarlota inquires at the local town office about the letter she’s received to inherit her mother’s estate, everyone looks at each other with ghastly expressions. Quickly, viewers see what director Nvotová is doing. As the close-knit village’s epithets begin to associate Šarlota with the town’s witch, who once lived in the cabin, she’s decided to reside in. This brings in Anna (Jana Olhová), a friend of Šarlota’s mother, who begs her to live in her house instead.

Šarlota’s introduction to Mira (Eva Mores), basking in the moonlight for a tan, recalls a similar scene in Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia, which shows an enlivened Kirsten Dunst moon bathing and brings it to the empowered aspects of Mira’s perceived wildness. Mira quickly tells us that she f**ks whoever she feels like and isn’t resigned to monogamous relationships. Still, there’s almost an implicit inference that the villagers think she hypnotizes men with her beauty as Mira’s married neighbor peeps on her and her lover through an open window and later tries to get her through violent means.

As Šarlota becomes fast friends with Mira, it seems more like Mira’s just living life authentically —open and unafraid. Mira offers Šarlota comfort when she confides in her about a miscarriage despite not wanting to have the baby. Mira tells Šarlota not to have kids if she doesn’t want them, opposing the Christian standards and immutable societal sentiment that, as a woman, Šarlota should have been happy being pregnant. In contrast, Anna’s daughter Helena (Juliana Olhová) offers a closeted queer character living in opposition to Mira’s sexual vivacity. Helena’s repressed by her village’s conservative views but finds acceptance in a sort of “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

With a strong emphasis on collective comfort versus individualism, Nightsiren takes shape. The film combines folktales and town gossip, authenticity versus subjugation, and advocates for freedom from these and other abuses. It’s a bit of a slow roll at the start and more aligned with contemplative societal ideology than a blood-and-guts horror flick, though there is enough tension in scenes to keep any thriller-lover satiated. The elevated Czech film’s central metaphor feels like a call to arms for female rights and a bucking of patriarchal domestication methods that overflow from traditional Christian values. Women in Nightsiren either adhere to the clique mentality on display in the village or become persecuted for living outside it.

Written with a sense of mysticality by Nvotová and Barbora Namerova, Nightsiren is a tale grounded in reality where noncompliance to the status quo is condemnable. The prodigal daughter concept for Šarlota’s return compounded with the town’s worried that her appearance is an omen of something sinister, further framed in the mysterious outsider horror trope. Despite having roots in the village, her welcome isn’t warm. Through her point of view, we see a place unaffected by an evolving world. In this village, women can never ascend beyond anything more than housewives who raise children, and any who don’t yield to that misogynist way of life are vilified. These characters’ perceived power as their friendship forms are seen as dangerous. Coincidental occurrences begin to serve as evidence of witchcraft in the village, concluding that the town is under attack by the women, which descends into a modern Salem when children go missing.

Nightsiren uses witchcraft elements in a muted fashion with commentary on the spinster, hag, or crone tropes used in films portraying witches, suggesting the denigration of women who didn’t fit beauty standards or were uninterested in playing by the accepted rules of a male-oriented society. The writing is such an intricately woven tapestry of feminine oppression, and that’s where the movie truly succeeds. Additionally, Federico Cesca’s cinematographer abilities deserve praise for offering plenty of ambiance in the hillside greenery as he does when capturing a cliffside.

Directorially, there is a lot of imagery in the film inspired by The Wicker Man. Yet, Nvotová keeps the pace together by intercutting the movie with flashbacks and keeping Nightsiren from ever feeling like it’s traveling down the same path. However, the movie does feel slightly elongated in places, treading over territory it’s already traversed to drive its point home. The film’s big twist isn’t hard to see coming either, though that’s due more to the chemistry of the actresses, which I wouldn’t change for the world. Regardless, Nightsiren delivers a folktale that debunks witch stereotypes and asks that we accept people who don’t want to operate within the confines of what’s traditionally been considered acceptable.

Nightsiren played as a part of The Boston Underground Film Festival and is currently playing on the film festival circuit.