Lars von Trier is a horror genre icon that disturbs viewers to such a degree that they often reject him; his films are sometimes broadly dismissed as gratuitous, torpid, or languishing. The latest, The House That Jack Built (2018), notoriously incited a mass walk—out at the Cannes Film Festival for its depiction of a serial killer executing children and desecrating their bodies. Before and since that premiere, many of von Trier’s audiences have been compelled to look away—shaking their heads and wondering, “Why was this film made?”

Von Trier’s earlier works are less apparently imbued with the horror affect than The House That Jack Built, in part because they are suffused with a florid, engrossing style that subverts the pacing, structure, composition, and sound typical of horror films. Despite this habitual undermining of genre conceits, von Trier’s films are replete with the trappings of horror concepts and scenarios: apocalyptic cataclysm, sociopathic mothers, inexplicable murder, tormented hauntings, nihilistic sex, you name it.

But it is more than this narrative association with horror that iconizes von Trier in the genre—otherwise, he might hover in the classification of avant-garde or might even just exist as a filmic hack. There is a reason why von Trier’s films are shrouded in opprobrium and disgust, why people recoil from them, and this inscrutable quality is culled from the director’s own experiences with mental illness.

There is no getting around it: these movies are just plain hard to watch. Misery is woven into the fabric of von Trier’s films, down from their thematic elements and up through their arrangement and editing. Even I, a proud enthusiast of all things grim in TV/Film who regularly inhales grisly horror and the darkest of comedies, needed three separate attempts to get through Antichrist (2009). My desultory slog through the anxiety-inducing, frustrating, and confusing atrocities that are depicted (or implied) in Antichrist’s grueling, protracted plot finally granted me insight into the method of von Trier’s literal madness.

Lars von Trier horrifies and antagonizes us because he constructs an inescapable vision of human depravity. Not only does his destabilizing portrayal of human nature affront us with unexpected personal examination, it also communicates this unacceptable notion through exquisite artistic innovation that confounds the impulse to reject its connotations. Here, we’ll qualify the horror of von Trier by examining his—you guessed it—Depression trilogy.

Malaise, dysphoria, revulsion

Most of von Trier’s filmography precedes the Depression trilogy and The House That Jack Built, and his work warrants examination in its entirety. Nonetheless, we will leverage only these later works to explicate his contributions to the horror genre as offered through the lens of mental illness. Antichrist (2009) is the foreboding little film that commences the Depression trilogy. In Antichrist, which stars Charlotte Gainsbourg as “She” and Willem Dafoe as “He,” a husband’s methodical, psychoanalytic plumbing of his wife’s anguished despondency yields insight into her distorted but impervious discernment that womankind is inherently craven and evil.

Let’s suffice to say that only one of them leaves the rural cabin that the couple withdraws to for homespun therapy. The grueling tedium of Antichrist’s pacing coalesces into a devolution of meaning and a breakdown of the social order as embodied between husband and wife. Palpable listlessness in Antichrist is also disquieted by unsettling sound effects and searing imagery that escalates in intensity: a doe with stillborn fawn hanging from her haunches, a self-cannibalizing fox that weirdly verbalizes an omen, and (of course) extreme violence, including uncut shots of genital mutilation.

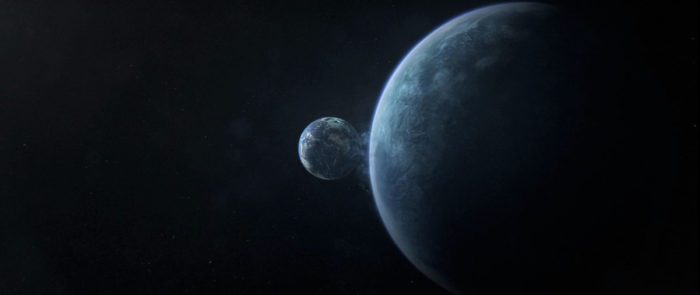

Antichrist is the only feature in this trilogy that is explicitly classified as horror, but the films that follow it also rework the devices of destruction, inevitability, and frenzy in ways that qualify von Trier as an invaluable contributor to horror. Melancholia (2011) is a horror/science fiction film that depicts the total annihilation of the earth by collision with a rogue planet with the designated, titular name: Melancholia.

Melancholia is divided into two ostensibly unrelated parts. Part I depicts Justine’s (Kirsten Dunst) painful wedding reception at her sister Claire’s (Charlotte Gainsbourg) stately home. Depression and social dysfunction inhibit Justine from connecting with her husband or anyone else, and she frequently abandons the reception for extended periods only to return to the torturous party that seems to never end. Melancholia, Part I ends with Justine calling off her marriage and quitting her job, essentially abdicating her connection with life.

In Part II, also set at Claire’s family home, Justine’s depression affords her special knowledge about the impending impact of Melancholia with Earth. The interplay of the family’s ‘healthy’ expectation of a planetary fly-by with Justine’s renewed assurances of imminent destruction sustain the film’s narrative. Von Trier centralizes the characters’ different emotional reactions to an astronomical catastrophe to dramatize emotional and ideological tension between sane and unsound minds. And, like Antichrist, the prolonged, tedious pacing of protracted scenes viscerally conveys the sensations of depressive perception and have a paralyzing effect on the viewer.

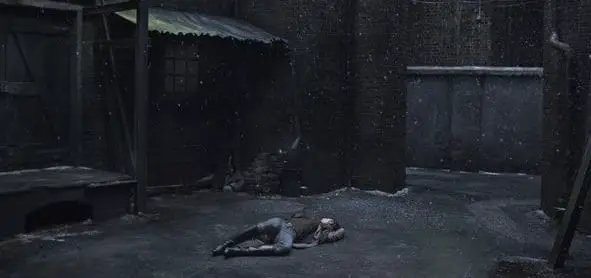

The final installment of the Depression trilogy is Nymphomaniac (2013), released serially in Volume I and Volume II. The entire plot takes place inside a scholarly male virgin’s apartment. The virgin, Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård), finds the nymphomaniac, Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg), lying bleeding and unresponsive in an alleyway and helps her, taking her to his apartment, giving her pajamas, and putting her in bed. She expresses that she deserved the beating she received because she is inherently bad. Seligman protests her self-deprecation, so Joe illustrates her inherent badness by regaling him with her story of lifelong sex addiction. This framing device enables the extended narrative of the film, which traces Joe’s profligate career as a nymphomaniac and ultimately bears explanation for how she ended up in Seligman’s alleyway. When her story is finished, Joe confides that Seligman is the closest thing to a friend she’s ever had, but he ultimately betrays her by attempting to have non-consensual sex with her. So, she kills him.

The thematic arc of the Depression trilogy qualifies it as cinema that is—more than anything else—discomforting and deeply unsettling. Each protagonist perceives herself, and by extension all of humanity, to be inherently evil, and each film’s resolution is grounded in sheer hopelessness. Von Trier escorts us through portrayals of depressive mental illness that arise from lived experience; from atypical grief and psychosis to major depression and neurosis, we are immersed in a worldview that perceives mankind itself as a horror from which the only escape is obliteration. It is this agitating quality of von Trier’s work that qualifies it as unequivocally provocative.

Through his inventive reworkings of filmic devices and style, he compels us to engage in new ways with monstrosity, which in the classical sense implies terrifying imagery that serves as a reproachful warning. This essential meaning of the word monstrosity denotes the indispensable qualities of the horror genre: hideous scenes that allow us to mentally explore real or imagined dangers in our world. It is widely acknowledged that the films of von Trier’s Depression trilogy elicit disgust and discomfort. But are they terrifying? Do they truly evoke the definitive elements of horror—fear and dread?

The destroyed and destroying woman

In the Depression trilogy, there is distinct tension between male agency, associated with rationality and order, and female subversion of that demand for control. These thematic issues are interlaced with such profane and disturbing sequences that they come to instill a sense of inescapable dread and disorder. In all three films, the breakdown of the familial and social order is the recurring outcome, and the female protagonist’s dissatisfaction is always the catalyst for destabilization. The protagonists’ unruly sexuality is also directly connoted with the natural world and with entropy. Recognizing this thematic undercurrent, some critics have maligned von Trier’s work as misogynistic. However, they fail to recognize von Trier’s strong identification with women who contort the social and sexual order in what is essentially a gruesome struggle for power and autonomy.

The antagonistic relationship between male and female power is also represented by multiple allusions to witchcraft and the brutal repression of women throughout history. In Antichrist, the wife’s abusive and self-effacing actions arise from her immersion in a thesis study on the Burning Times—the early modern era of witch trials and executions, or “Gynocide.” Her initial attempt to study the issue of brutal female subjugation from an objective distance deteriorates as she comes to recognize the implicit dynamic of hierarchical power in her modern surroundings and in her relationships. Instead of overcoming the historical annihilation of female agency, her thwarted thesis discomfits her, surging into an irrepressible rage. Nature as a contaminant or as a destructive force is a major theme in Antichrist, and this subversive quality of nature is furtively linked to the wife’s unrestrained and devious sexual urges.

Undertones of witchcraft represented through caustic female agency are also primary thematic elements in Nymphomaniac. Joe describes that in her youth, she and other young women form a club called “The Little Flock” that has the objective of impiously and resolutely fucking as many men as they can, with the strict stipulation that they do not form an emotional attachment. At their meetings, one member plays the Devil’s Tritone on the piano while the others participate in a ritualistic chant: mea vulva mea maxima vulva. Symbolically, The Little Flock is committed to rebellious female liberation from structured power dynamics of male-female relationships, but they ultimately prove unable to extract themselves from the ideological snares that entrap humans in hierarchical chains of dominance and submission.

In Melancholia, Justine’s depression strongly links her with the death-dealing planet (Melancholia), but also causes her to believe she has uncanny powers of supernatural knowledge. She tells Claire, who craves order and stability, that she has a special ability to know that Melancholia is going to destroy all life on earth, that life on earth is the only life in the Universe, that she is glad it will happen because the earth is evil, and she qualifies her ability to know by guessing the amount of beans in a jar from her wedding reception. Justine’s rejection of or inability to comply with life’s social order that is communicated in the first part of the film makes her an unnatural, obscure character, and the film’s confirmation of her dark vision of reality constructs an overall sense of chilling, impermeable futility.

Justine’s sexuality also sustains the theme of woman’s destructive, irrepressible connection to nature. In Part I, her wedding night, she never consummates her marriage with her husband and instead has wild, unsatisfying sex with a different man outside in the grass. This unfixed, implacable misdirection of sexual energy is contrasted with a scene from Part II in which Justine experiences sexual longing and gratification from her inner compulsion for the planet’s destruction by Melancholia. Claire follows her transfixed sister to the riverbed in the woods at night and finds her lying naked, soaking up the rays of the moon and of Melancholia. Her posture, the composition of the scene, and swelling music all connote consummation, sexual satisfaction, and pregnancy. Justine’s denial of life and positive embrace of wholesale destruction conflate with allusive imagery to germination and conception in the planetary collision to illustrate the depressive longing for death. That Melancholia and the other Depression films confirm these bleak outlooks contributes to von Trier’s nuanced skill at composing a narrative of inexorable existential horror.

Lars von Trier expertly applies stylized imagery to his films in purposeful shots that emulate living paintings and that encapsulate multiple narratives with interconnected thematic elements. By striving to attain a sublimation of depressive inclinations through film, von Trier engages with inventive portrayals of nature and womankind through elaborate simulacra. His construction of inescapable visions of the inherent depravity and senselessness of human life serves as a validation of depressed rumination. The grotesque quality of his inventive style conveys hyper-realistic, lingering scenes that echo depressive perception. From his experimentation with realism and his pushing the envelope with audience tolerance, we are left to contend with the bleak impression that the obscure messages in his films bear actual meaning. For instance, consider the theories of depressive realism and cognitive advantages of depression—could it be that the despondent vision of human nature offered in von Trier’s films is an accurate depiction of reality?