I’m pretty sure you could take anyone who has never even heard of heavy metal, show them a picture of any heavy metal performer in the world and they’d probably guess, “gee, that person has probably watched a whole ton of horror movies!” So, when this new documentary posits that there might actually be a bit of a connection between horror and metal, I didn’t exactly go in with a skeptical eye. I had hoped that The History of Metal and Horror would have provided a little more insight into the two genres than it did though, with the film taking an hour and 40 minutes to tell us that a) both genres act as a means to confront the darkness in humanity and bring it into the light and that b) they use a lot of similar imagery of death and gore to do so.

The film’s appeal does mostly lie in seeing a bunch of heavy metal royalty gush about their favourite and most formative horror movies and shout out a few bands they consider underrated or seminal. It’s fun enough but it requires a pretty heavy investment in both genres to appreciate at all. I love horror and metal in so far as I love cinema and music, though my tastes in both are generally a little more cerebral. So, I quite enjoyed it, but it most definitely wore out its welcome and became a bit of a chore, falling quickly into redundancy and repetitiveness, particularly as it tries to bring itself to something of a conclusion. The point of a conclusion is to restate the key points we’ve discussed and pull back to the bigger picture, but The History of Metal and Horror never really went into the subject with much depth anyway. I say you’d have to be more invested in both genres than I am to enjoy the film, but you’d have to be much less invested than me in order to learn anything.

Probably the one piece of insight I did gain by watching was learning that along with the “video nasties” list of banned horror movies in the UK, America had it’s own “Filthy Fifteen” of banned songs, predominantly heavy metal, with horror and heavy metal co-defendants in the “Satanic Panic” scare. This is the kind of interesting, actual historical detail the movie could’ve delved into more. We hear in passing that the moral panic around heavy metal ruined lives and careers, but we don’t get any specific examples cited, as we would in a more thoroughly researched deep dive.

Instead, what The History of Metal and Horror offers is the generally endearing spectacle of artists like Alice Cooper and Corey Taylor talk about their favourite horror movies, leaning more on passion and enthusiasm than eloquence or insight. Cooper is actually one of the few interviewees with some real anecdotal weight to his contributions, as he gets to talk about getting cast in John Carpenter‘s Prince of Darkness and how his onstage effects were worked into the film. He’s also cited by other interviewees as a seminal influence in the foundation of heavy metal and its crossover with horror, although the early crossover moments like the influence of artists like Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Arthur Brown or Screaming Lord Sutch are just mentioned and then dropped.

Although we get clips of the films under discussion, sadly we don’t get much of the music, with the film scored entirely by just three bands: The Judas Syndrome, Knights of the Black and Metal Jacket. Licensing music for films is expensive, but it’s a real detriment that we don’t have illustrative examples, making the crossover between the two genres look more purely aesthetic and shallow than it need have. The status of the genres as counter-culture also feels underexplored and uninterrogated, with the film never critically examining anything, remaining purely celebratory rather than introspective.

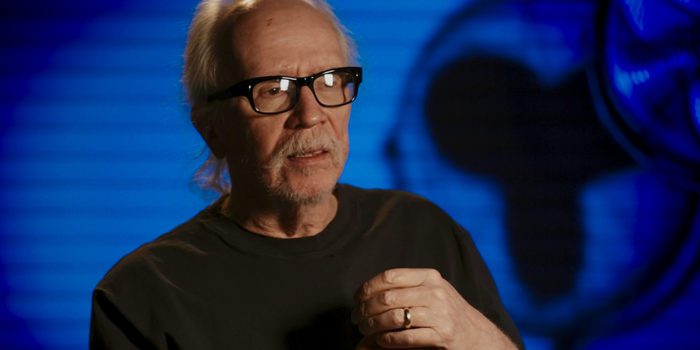

There is an enviable lineup of metal heads and horror icons like Doug Bradley, John Carpenter and Kane Hodder, though perhaps there are too many voices each getting their screentime, resulting in a lot of redundancy where one interviewee will make a point and it’ll get reinforced five or six times by others before we move on. It’s nice to give some more obscure artists their spotlight, and I’d have liked to have seen more diversity among the interview subjects, who are mostly American, mostly white and mostly male, as are the artists discussed. It’d have been more forgivable to have so many perspectives if they weren’t all so uniform in their journey to and experience with the genres. Thankfully one voice we don’t get is Marilyn Manson, who of course comes up a lot but who doesn’t appear, although we do get Doug Bradley’s reminiscence: “I have been kissed by Marilyn Manson, you don’t get over that in a hurry!”

Sadly, the weakest part of the film is the framing device containing it. A fictional end of the world scenario, clearly inspired by the ongoing pandemic, where the last man alive discovers the film on some old cassette tapes, with a sinister presenter addressing him directly. It’s tongue in cheek and appropriately cheesy, establishing an eccentric, oddball tone but it drags on a bit and brings the pace to an emergency stop whenever we cut back to it. Humor and excess are a keystone of both heavy metal and horror, as Alice Cooper observes about horror: “it’s comedy,” and this framing device, together with the in-character contributions of the band GWAR do keep the tone appropriately irreverent, but I think more wit could’ve achieved this tone better.

There’s certainly some fun to be had with The History of Metal and Horror, with its own niche appeal guaranteed to secure a captive audience with its intended crowd who it’s unlikely to challenge. However, it’s appeal is pretty limited in scope, lacking the insight or rigor to inspire the appreciation of those who have not been uncritically marinating in heavy metal culture for the past decade or so.