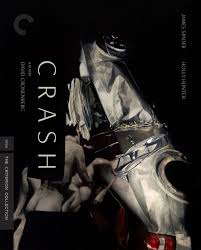

Many people have a difficult time driving by a car crash or a train wreck without craning their necks to get a better look. It seems to be human nature to have a desire to take in these sorts of images, which is probably why people enjoy horror films so much. What is with this morbid fascination? Is it a taste of death? Is it a chance to look behind the veil of what may come after? Perhaps we’ll never know, however, actor/director David Cronenberg looks at that very idea in his 1997 movie Crash, recently released on the Criterion Collection.

Crash, not to be confused with the 2004 movie of the same name, centers around TV director James Ballard (James Spader) who discovers an underground sub-culture of scarred car crash victims who find eroticism in reliving crash scenes. Ballard and his wife become deeply entrenched in the group after his collision with the beautiful, enigmatic doctor, Helen Remington (Holly Hunter) in which her husband is killed. Ballard and his extremely bored wife use the group to spice up their marriage—trying on a new fetish, if you will. Catherine Ballard (Deborah Kara Unger) becomes involved with the group leader, Vaughan (Elias Koteas), while James becomes involved with both Vaughan and Helen. Let’s be honest, it’s a free for all; everyone is involved with someone, or a couple of someones, in the group.

There are a couple of different horror subgenres at work in this film. Crash brings the idea of mortality and what it looks like to stare death in the face to the surface. In one scene, Vaughan and his friend Colin Seagrave (Peter MacNeill) reenact in front of a full crowd of onlookers the crash in which Hollywood icon, James Dean, lost his life. Their reenactments are done exactly as the crash really happened complete with the lack of seatbelts or any other personal protective equipment. The psychological ramifications of this type of reenactment are two-fold. One, the participant can stare down death—to play chicken with it. Second, the audience can take in an up-close and personal view of a tragic car accident. This could be fulfilling for both audiences as the participant is able to “conquer” death (or at least that’s the hope) and the spectators are able to “view” death without being too concerned that those involved will be fatally injured. It’s a cathartic release for all.

The second subgenre at play in this film is what seems to be Cronenberg’s favorite—body horror. There are some gnarly scenes in this film which no doubt played a large part in it being one of the first NC-17-rated releases in the United States (not to mention the constant sex scenes between everyone in the group that no doubt played a part). Roseanna Arquette plays a character who is so badly injured in a car accident that she is now more metal than human, and she has a scar on the back of her leg resembling the Grand Canyon. Throughout the film, there are numerous examples of mangled bodies fused with metal and glass giving viewers an idea of what it might be like to become part machine. As usual, Cronenberg zeros in on the ugliness and pain of life and manages to marry it with eroticism. This marriage makes the viewer question if it is not a comment on how sex can sometimes be seen as violent and the orgasm seen as “the little death.”

This film was controversial from the very moment it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival where it won a Special Jury Prize for “originality, for daring, and for audacity.” It has since claimed its place as a key part of late-twentieth-century cinema, a cult classic, focusing on the seductive thesis of relationships between humanity and technology, sex and violence, and the human desire to hold hands with death.

The film itself has some problems, a large one being Deborah Kara Unger’s performance which shows no signs of life. She spends the entire movie looking bored and emotionally detached. Her performance makes one question if it is actually horrible acting or complete genius. Her character is tired of her marriage. She and her husband are open in their dalliances with other people. In fact, they come home and tell each other about it. However, this doesn’t seem to be enough any longer and they are obviously searching for something further into the darkness—something that will take them to the brink. At the end of the film, after a particularly bad car accident, Catherine is laying on the side of the highway next to the wreckage. James is holding her and trying to make sure she is ok. She begins crying. At first, we believe that she is crying out of pain or fear due to what she has just been through. When we become privy to their conversation, we understand that she isn’t crying about that, but she is crying because she wasn’t hurt in the accident. She is still whole. It’s at this time that James says, “maybe next time.” This begs the question of what could make these people so unhappy and so unfulfilled and what will be enough? It feels as if Cronenberg is taking this opportunity to comment on the human condition and how we are never satisfied. We are willing to do wild and even stupid things in order to find that next plateau. When will it ever be enough? That seems to be the question that he posits in this last scene of the movie.

It is questionable as to whether Crash is a horror movie or more of a psychological thriller. I’ll let you decide. From my perspective, it is definitely a comment on the horror that people can put each other through in the search of something deeper, something that gives life meaning. To me, it feels adjacent to another of Cronenberg’s movies, 1977’s Rabid in which a young woman develops a taste for human blood after experimental plastic surgery. Like Crash, Rabid comments on how humans are never satisfied, and our journey to find some type of fulfillment often leads to ruin. If you’ve got some time, watch these two together and let me know what you think.