In my last article, I devoted over 3,000 words to poring over the finer points of Pieces (1982). This time around, drawn once again by the siren call of crap, I’m discussing The Prowler. Both Pieces and The Prowler are—by almost any conventional metric—objectively bad movies. The chief difference between them is that, while Pieces is bad in a wonderfully idiosyncratic way, The Prowler is bad in the very pedestrian way that many bad movies are bad. In the case of The Prowler, the major issue is a poor script that lacks structure, relies heavily on repetition, and often drags when it should be ramping up the suspense.

So, if The Prowler isn’t a very good movie and it doesn’t have the same wacky charm as Pieces, you may be asking, “Why are you writing about it?” A fair question (but, also, how dare you). The answer is that for some reason, of all the non-franchise 80s slashers—including The Burning (1981) and My Bloody Valentine (1981), both of which are better movies in nearly every regard—The Prowler is the one I’m most fond of. Unlike Pieces, which I like largely because of its flaws, The Prowler is very much a movie I like in spite of its flaws. And while those flaws are neither few nor minor, for me the things the movie does right manage to outweigh them.

Local College to Hold Graduation Dance; Local Vet Not Happy

The whole jilted WWII G.I. angle is unique in all of slasherdom. From the curveball opening of faux newsreel footage to the 1940s dance to the killer’s unique look, The Prowler is a slasher unlike any other. Regarding the killer’s look, I think it’s close between this movie and My Bloody Valentine when it comes to the most iconic slasher villain who isn’t Jason Voorhees or Michael Myers. With the dark fatigues, boots, helmet, and weird mesh face covering, the killer in The Prowler is a uniquely imposing figure.

I remember first seeing the VHS cover for The Prowler as a young kid. I knew nothing about the movie and I remember that I was confused as to what “the prowler” actually was. I didn’t recognize his get-up as WWII G.I. garb; to me, the dark, featureless figure had an almost inhuman quality, as if perhaps “the prowler” were some kind of monster.

A few years later, still knowing nothing about the movie, I saw a brief clip from it while watching a documentary on TV about horror movies. It must have been the scene in the swimming pool because I remember the killer emerging from the water to attack his victim. Again, I couldn’t tell just what it was I was looking at. Though I wouldn’t see the movie until decades later, the memory of those fleeting images held fast in my mind. Of course, once I did finally see the movie, I understood that the killer was just a guy in WWII-era combat gear and not some kind of monster. However, I still found it very effective. Perhaps because it just feels so out of place—in much the same way Jason’s hockey mask feels utterly incongruous.

I mentioned the look of the killer in My Bloody Valentine, and there are certainly visual similarities between the killer in that film and the killer in The Prowler. I would argue that, while the miner’s suit and mask are very cool, due to My Bloody Valentine’s setting there isn’t the same clash between the killer’s appearance and his surroundings. Given how much of My Bloody Valentine takes place in or around a mine and that it centers on characters who are miners, the killer’s get-up doesn’t feel unnatural. On the other hand, the sight of a figure clad in WWII-era fatigues, his face obscured by a mesh hood, cannot look anything but unnatural—even surreal–in such decidedly mundane and thoroughly civilian settings as the well-lit bathrooms, dormitories, and swimming pools of a small-town college in 1980.

Story? Characters? Man, I’m Just Here for the Kills

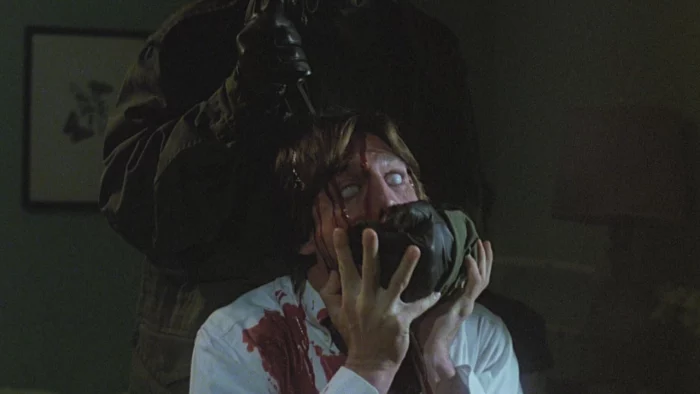

The Prowler has, almost inarguably, the best kills of any slasher movie ever. Even among 80s slashers, these kills stand out for their inventiveness as well as for their sheer brutality. Probably because it was not distributed by a major studio (more on that later), The Prowler managed to avoid the heavy editing that other slashers were subject to. As a result, the film often lingers for an unsettlingly long time on its gruesome, set-piece murders. One notable example is the bayonet through the top of the head kill. While it doesn’t make much sense—I’m fairly sure there would be little to no struggle involved, as the victim would likely be dead immediately—there is no denying that the time devoted to showing it, without cutting away, greatly increases its effectiveness. I would also point out that while I question the medical accuracy of the victim’s eyes rolling back in his head as he dies, it makes for a striking and unforgettable visual.

Another example of the film’s unremitting brutality is the murder in the swimming pool. The murder itself—a throat-slashing as the prowler emerges from behind the victim while she struggles to escape the pool—is certainly vicious enough on its own. However, for me, it’s the kick to the face when she first tries to exit the pool that cements this scene as one of the most brutal in slasher history. Unlike the bayonet through the head kill, which looks great but isn’t very realistic, there’s something about the simplicity of a kick to the face that makes the pool sequence feel more realistic, meaner, and nastier than what you get from most slashers.

While it’s not as gloriously sleazy as Pieces (few films are), the pitchfork shower murder alone makes The Prowler probably the sleaziest 80s slasher not directed by a European (e.g., Juan Piquer Simón, Lucio Fulci, Joe D’Amato). To its (dis)credit, not even Pieces features a scene that so gratuitously incorporates both nudity and graphic violence. The shower kill in The Prowler is like the anti-Psycho shower scene; where the murder of Marion Crane uses skillful camerawork, editing, and music to suggest far more than what we actually see, The Prowler suggests nothing and leaves nothing to the imagination. It lingers and leers at the sight of the pitchfork’s tines piercing the victim’s flesh, all the while making sure that her breasts are on full display.

If a critic of slasher films were looking for one scene to embody all that is “wrong” with the subgenre—the standard accusations of sexism, misogyny, misanthropy, the celebration of violence—it would be difficult to find one better than this. It is, unquestionably, exploitative as hell. It’s also ugly—in every sense of the word. It is also, however, terribly effective, extremely memorable, and genuinely shocking. And one could say the same for The Prowler as a whole—well, about the kills, anyway. Admittedly, the rest of the movie is less transgressive than tedious, as we are subjected more than once to long stretches of our two protagonists just walking around.

I cannot, in good conscience, give The Prowler a full pass for this; even a slasher should try to offer something at least moderately interesting between kill scenes. However, the quality of those kills goes a long way. Indeed, thanks to the intensity and mean-spiritedness of its kills, The Prowler stands out from the vast majority of its 80s slasher counterparts. In fact, it feels more closely related to grittier, quasi-slasher films like Maniac (1980) and The New York Ripper (1982) than it does to the Friday the 13th series and other, more mainstream slashers.

Sandhurst Films? More Like Sandworst Films

If you do an image search for The Prowler movie posters, the two that come up most are the one that was linked to earlier in this article and this one. While both are good, I love the second one. I think it’s one of the all-time best slasher posters, maybe even one of the all-time best horror movie posters. I love the black and white minimalism—an ironic choice considering how very non-minimalist the movie is. I even like the “It will freeze your blood” tagline, despite its being fairly generic and having no specific connection to the movie. Actually, when it comes to taglines, The Prowler had quite a few. Among them: the equally generic but still respectable “If you think you’re safe…you’re DEAD wrong!” (from a UK poster featuring the title Rosemary’s Killer, as the film was known internationally) and, my favorite, “The Human Exterminator…he has his own way of killing!”

Now, why the killer from The Prowler is more deserving of the title “the Human Exterminator” than any number of other slasher villains, I don’t know (really, in terms of sheer body count, surely Jason is the Human Exterminator); nonetheless, it has a great ring to it. I also quite enjoy the rather bold proclamation that “he has his own way of killing!” Again, I’m not really sure if it makes sense–clearly he has no patent on the use of sharp implements for stabbing and slicing—but it sounds cool. And when it comes to exploitation horror flicks, having a cool poster and tagline is roughly half the battle.

Or, at least it should be; despite such killer marketing materials—and despite being released at the peak of the slasher craze—The Prowler was an abject failure at the box office. This can almost certainly be attributed to the fact that rather than being distributed by Avco Embassy Pictures, who had expressed interest in the film and whom you may have heard of, the movie was for whatever reason distributed instead by Sandhurst Films, whom you have almost certainly never heard of.

“The War in Vietnam? The War in Viet-f*cking-nam!”

It’s tempting—to me, anyway—to interpret The Prowler as a commentary on the potential for American military violence abroad—specifically the kind wrought by the US in Vietnam—to manifest on the home front: a lethal blowback engendered by the combined effects on returning combatants of both psychological trauma and the normalization of killing during wartime. Alas, such an interpretation would probably be a bit of a reach. Or, rather, it’s probably a reach to suggest that any such commentary was intentional on the part of the filmmakers.

However, it isn’t entirely implausible that in 1981, just six years after the end of the Vietnam War, such anxieties would have been “in the air,” so to speak. Perhaps even to such an extent that they found their way—albeit unconsciously or indirectly—into the unlikeliest of places. Like, say, a low-budget, exploitation slasher flick hoping to cash in on the runaway success of Friday the 13th?

If so, this could mean that the killer’s being a war veteran in The Prowler—which is, in any case, a very intentional choice—was perhaps a decision made unconsciously for its capacity to evoke post-Vietnam War anxieties such as a shaken belief in the fundamental justness of US military actions abroad and burgeoning awareness of the grim realities of PTSD (a term which entered the lexicon in, wait for it…1980).

Notably, while The Prowler doesn’t specifically mention PTSD—or even earlier terms like shell shock or combat fatigue—the faux newsreel that opens the film does briefly allude to the fact that many of the returning soldiers will need time to readjust to civilian life after experiencing the horrors of war—or something to that effect. The truth is that even this throwaway line is more than any actual newsreel from the time would ever have devoted to the subject of returning soldiers’ mental health. The recognition of the adverse psychological impacts of war on combat veterans in the years after the Vietnam War was a marked difference from the public discourse surrounding previous wars. In 1945, riding high on a wave of uniquely American triumphalism and optimism, acknowledging any potential dark side to the return of “our boys” from overseas would have been strictly verboten.

However, anachronistic as it may be, it does suggest that the filmmakers were aware of PTSD—or at least of something that had just recently received that appellation—and thought it significant enough to include in the film’s expository prelude. Rather than merely being an anachronism or a conflation of two decidedly different eras though, perhaps the film’s inclusion of a reference to combat-induced trauma in the context of WWII is instead part of the film’s unconscious “coding” of the Vietnam War as WWII. In this vein, the killer’s wearing what are very clearly WWII-era fatigues would be an instance of “coded” imagery; we see WWII but are very much meant to read Vietnam. Of course, the effectiveness of this particular coding would have come from the stark contrast between WWII and Vietnam in the popular consciousness, i.e., a “good” war (WWII) versus a “bad” war (Vietnam).

It is, of course, impossible to say with any certainty to what extent—if any—the Vietnam War influenced The Prowler. I would say only that considering the possibility of such an influence offers an interesting lens—though by no means a necessary one—through which to look at the film; and, given the national zeitgeist at the time of the film’s release, it doesn’t seem a wholly inappropriate one either.

You Know What They Say About Opinions, Right? Everybody Has One, and We Should Honor and Respect Them

Fortunately, the validity—or lack thereof—of any potential subtextual readings of The Prowler has little to no impact on one’s ability to enjoy it for what it is. The Prowler has a lot of things going for it: an original concept, a unique killer, great atmosphere and aesthetics, fantastic kills, and a more than solid final girl and final girl sequence. Unfortunately, it’s also saddled with an absolutely lackluster script, even by slasher standards. However, while that isn’t an insignificant problem, when it comes to slashers it really shouldn’t be a fatal one.

If you’re a fan of slashers and you haven’t seen The Prowler, you should. Just the fact that it’s one of the lesser-known releases from the peak year of the slasher boom makes it worth checking out. Add the fact that it was his work on this film that landed Joseph Zito the directing gig for Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter and that Tom Savini considers this his best work, and you’ve got some pretty compelling reasons to seek it out.

Just remember to temper your expectations: it is going to drag (especially in the second act), and it is totally going to squander having both Farley Granger and Lawrence Tierney in the cast, neither of whom is given very much to do in the film. Granger, of course, starred in the Hitchcock classics Rope and Strangers on a Train, while Tierney had been playing tough guys in films and TV since the 1940s. Perhaps most importantly though, Tierney appeared in Silver Bullet (1985) as the eponymous, Peacemaker-wielding proprietor of Owen’s Bar and in an episode of Seinfeld as Elaine’s cantankerous father, Alton Benes.

If you have seen The Prowler, then perhaps you too were charmed (?) by its rampant, stomach-turning violence, its oddball eccentricities, and its unabashedly exploitative grindhouse ethos. Or, perhaps…you were less taken with it. In which case, you may be wondering—especially with this apologia for The Prowler coming on the heels of an epic encomium to Pieces—why I don’t just follow my own rather cheeky advice regarding bad horror movies. Let me first say, in my defense, that I never said The Prowler wasn’t bad. In further self-defense, let me also say that I am obviously a massive hypocrite—so, you know, what did you expect?