One reason for the popularity of the ghost throughout horror culture is its narrative flexibility: the “rules” of the ghost seem to change with every new story, and its presence in a tale can therefore signify an inexhaustible range of traumas, repressions, and cultural fissures. Unlike more physical monsters such as zombies and vampires, ghosts are ethereal figures—there are no established, consistent rules for defeating them or making them go away.

At least in contemporary pop culture mythology, perhaps the most inevitable solution to a haunting is to somehow “do right by the ghost,” to acknowledge something that has not been spoken of in which the ghost has a pre-haunting personal stake. This silent secret is often a crime, such as murder, whose public solution satisfies the ghost’s need to be heard, as in such disparate films as The Changeling, Ghost Story, and Stir of Echoes. Other popular films, such as The Woman in Black, The Sixth Sense, and El Orfanato (The Orphanage), suggest a version of haunting associated not with justice but with the simple urge to embody personal trauma and have it be recognized by the living world. Films told entirely from the ghost’s point of view, such as A Ghost Story and The Others, indicate a kind of endless emotional vacuum in which time itself seems to be the monster, stretching out before specters who have little agency or influence and are, like the film’s viewer, merely observers of the cosmic mystery that we call life.

Julia Briggs notes that “Ghost stories constitute a special category of the Gothic and are partly characterized by the fact that their supernatural elements remain unexplained”—which means by extension that it is of course those human passions behind haunting that remain truly unexplained. [1] This observation seems even more apt in ghostly literature, which can process human psychology with perhaps more deftness than film can. Classic tales of haunting such as The Turn of the Screw, The Haunting of Hill House, and The Shining (not to mention any number of stories by writers such as Poe and Hawthorne, to name only the most canonical) reflect Briggs’ implication that the fundamental appeal of ghosts lies in their ability to reflect and then jump over the limits of human knowledge. The strange and shifting motivations of the dead are, in a good ghost story, metaphors and disguises for not only the contradictory impulses of the living but the “figures and conventions […] that link a sense of reality (or unreality) to structure of fiction.” [2] Ghosts tell us, in other words, not only what is tricky and scary in ourselves but what is tricky and scary in stories of ourselves. Ghosts may be real or they may be in characters’ heads, but they always prompt a need—perhaps an obsession—to tell.

Like so many other tropes in our contemporary narrative toolbox, popular paradigms of ghosts and hauntings come to us at least partially colored by the insights and imagination of William Shakespeare. [3] His ghosts, particularly the famous ones that show up in such plays as Macbeth, Hamlet, and Julius Caesar, anticipate most of the ways in which we understand ghosts as psychological traumas today. Flipping through a collection of Shakespeare’s most popular plays will yield early modern analogues to most of the motivations for ghostly behaviors outlined above. Shakespeare’s understanding of the relationship between physical trauma and haunted psychology, especially in his treatment of state-centered power enacted through the obsessive drives of powerful leaders, frequently leads him to take advantage of the figure of the ghost to represent the unresolved excesses of the political-that-is-also-personal.

Before the famous ghosts of Banquo, Caesar, and Old Hamlet, Shakespeare wrote about the complex possibilities of the undead body politic in Richard III (first printed in Quarto form in 1597). This play, which tells of the bloody ambitions of Richard of Gloucester on his path to becoming King of England, is an analysis of villainy whose protagonist is often seen as a sort of rough draft for Shakespeare’s more complex villains such as Iago and Macbeth. Richard is, however, a showman who understands how to use the very structures of his government and social scaffolding to achieve his goals, and therefore as we watch him maneuver past one and then another and another obstacle on his way to the throne we are watching not only the designs of an evil man but the expectations and architecture of his society. When ghosts appear in Act V to curse Richard to his doom on the eve of his final battle, then, we see a haunting that helps Shakespeare articulate the intersection of the personal and institutional that has influenced the legacy of prophetic ghosts even to our own day (see “Ghosts in Shakespeare” by John Mullan for some context about Elizabethan ghosts more generally).

King Richard, Haunted

Richard III is, on the surface, an extremely practical story. Unlike Macbeth, whose bloody banquet ghost and gibbering grief-crazed handwashing scene seem at home among an entourage of witches, desolate fog-bound heaths, and visions of daggers bedecked with “gouts of blood” (II.i.46), this play depicts an almost bureaucratic evil. In his opening speech, Richard announces, “I am determinèd to prove a villain” (I.i.30) through practical schemes: “Plots have I laid, inductions dangerous” (I.i.32). Richard then manages to kill off everyone who stands in his way—but he does so largely by relying on the governmental practices already in place (since death is the punishment for a wide array of suspicious behaviors, Richard ensures that his obstacles are seen by the established powers as dangerous to them). Only after he is crowned and, like Macbeth, succumbs to paranoia about keeping the throne does Richard go truly outside the art of the possible, ordering the murder of the two young princes who represent a more legitimate claim.

The appearance of ghosts at the climax of the play, then, might seem a somewhat awkward move on Shakespeare’s part, since by nature ghosts represent an appeal to systems of understanding that are inherently unstable and volatile compared to the issues of lineage, succession, and royal legitimacy on which Richard has grounded his wickedness. These ghosts, however, perform an important function in Shakespeare’s concept of the character and the society in which he moves, because they prompt the only moment of potential sympathy for Richard that the play allows—in effect breaking through the performance of evil that Richard creates and on which the entire play depends for its dramatic effect. The ghosts, in other words, are the only element of the play that makes Richard human and relatable. Stephen King has suggested that ghosts are scary because we see ourselves in them; [4] if this is true, then the ghosts in Richard III help to establish this effect by making us fear not the supernatural but the potential evil in ourselves.

The ghosts that we see in Act V are the spirits of characters who appeared earlier in the play and were, in one way or another, killed by Richard’s machinations. None of them died literally at his hand: Hastings, Rivers, Gray, Vaughan, Lady Anne, and Buckingham died on the block after Richard turned on them in his gradual seizure of power, while his brother Clarence and the famous young “Princes in the Tower” were murdered by hired assassins (the previous King, Henry VI, and his son Edward were killed by Richard in battle before the action of the play begins). Richard expresses no particular emotion in response to any of these acts; they are simply the cost of doing business and getting what he thinks he deserves. The ghosts themselves appear to Richard in his sleep the night before the climactic battle in which he will be killed. Each of them steps forward and offers a brief condemnation of Richard’s treachery and (save Buckingham, who speaks last) each chillingly commands Richard to “Despair and die.” Richard then wakes up and offers a soliloquy in which, for the only time in the play, he judges himself for his deeds rather than glorifying them. He then shares this moment of introspection with his lieutenant, Ratcliffe, before turning to the battle at hand, where he is killed by the Earl of Richmond, who will replace him on the throne as Henry VII.

This is a remarkable scene, not just for the narrative arc of the character and play but for the development of ghosts in literary culture. It presents a very specific relationship between the haunters and the haunted, between the idea of ghosts as characters vs. as psychological constructs, and between historical and contemporary expectations of what ghosts are in a story to do. In the remainder of this article, I would like to sketch out some implications of this scene for our understanding of ghosts today in popular culture and then describe a personal example of how this understanding was applied in a recent production of Richard III.

Emily Shortslef notes that in Shakespearean scholarship this ghost scene “explicitly evokes […] the antagonistic exchange that early modern writers believed to take place between a person and his or her conscience” (119). [5] Shortslef’s own analysis emphasizes the degree to which the ghosts represent not merely Richard’s internal conflict but his engagement with the specific “injured others” that Richard has killed (119), and she, therefore, analyzes their effect as “visible, speaking presences” rather than just aspects of Richard’s own personality come finally to haunt him (122). This identification is important because it places these ghosts in a somewhat hazy middle ground between ghosts as physical embodiments of internal trauma and ghosts as people who have returned.

Richard’s ensuing self-analysis is real. Unlike Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, or Hamlet, Richard’s reaction to his haunting does not appeal to the possibility of madness in association with these ghosts—to hear their message is entirely a practical matter. He is able to assign the presence of the ghosts to a dream, rather than literal reality but notes that “Cold fearful drops stand on my trembling flesh” as a result of his vision (V.iii.179). Significantly, however, Richard transfers the fear they create to himself. Unlike, say, Macbeth’s fear of the undead—“If charnel houses and our graves must send / Those that we bury back” (III.iv.72-3), [7] Richard declares instead, “What do I fear? Myself? There’s none else by” (V.iii.180). He also notes that there is nowhere to go to escape the implication of such visions: “Then fly. What, from myself?” (V.iii.183).

There is a back and forth in Richard’s post-ghost analysis of himself, and the drama of the scene comes from the novelty of Richard’s lack of confidence and his equivocation (as Hamlet would say) in questioning himself: “I am a villain. Yet I lie; I am not” (V.iii.189). He finally settles into a self-pitying anticipation of his lonely end:

I shall despair. There is no creature loves me,

And if I die, no soul will pity me.

And wherefore should they, since that I myself

Find in myself no pity to myself?

Methought the souls of all that I had murdered

Came to my tent, and every one did threat

Tomorrow’s vengeance on the head of Richard. (V.iii.198-204)

When Richard admits that he feels fear for the first time, Ratcliffe tells him to “be not afraid of shadows” (V.iii.213), but Richard admits that

By the Apostle Paul, shadows tonight

Have struck more terror to the soul of Richard

Than can the substance of ten thousand soldiers

Armed in proof and led by shallow Richmond. (V.iii.214-17)

What we see, then, is on the surface the kind of ghostly visitation we might expect in a contemporary ghost story: an unrepentant villain is haunted by specters that force him to confront dark truths about himself that, upon waking, he will for the first time speak aloud and confirm. This is, in other words, essentially a Scrooge story—or, if you like, a Ghost Story story or even a sort of Sixth Sense story, in that the point of the haunting is not the fact or identity of the ghostly visitor but the articulation of a truth about the living character who is haunted.

But Shakespeare’s vision of ghosts is more complicated than that because he dramatizes here a strange nexus of power and powerlessness on the part of the ghosts. On the one hand, the ghosts seem to have the ability to influence the future: their repeated mantra “Despair and die” is precisely what happens when Richard awakens in turmoil and is soon killed on the battlefield. On the other hand, the ghosts actually achieve nothing, since Richard’s reaction to the haunting is initially self-reflective but ultimately irrelevant: his death represents no particular logic or narrative structure; he fights his adversary and is killed with no catharsis or atonement or even Iago-like doubling-down on his evil.

What, then, is the point of the ghost scene at all? As I have suggested, it provides a brief moment of introspection and self-awareness, but since that moment has no effect on the resolution of the plot or Richard’s real character arc, we are looking at an inflection point rather than a turn, a scene that emphasizes rather than affects. In the company of other Shakespearean ghost scenes, this one feels at once dramatic, menacing, and…something of a letdown.

One Production’s Approach

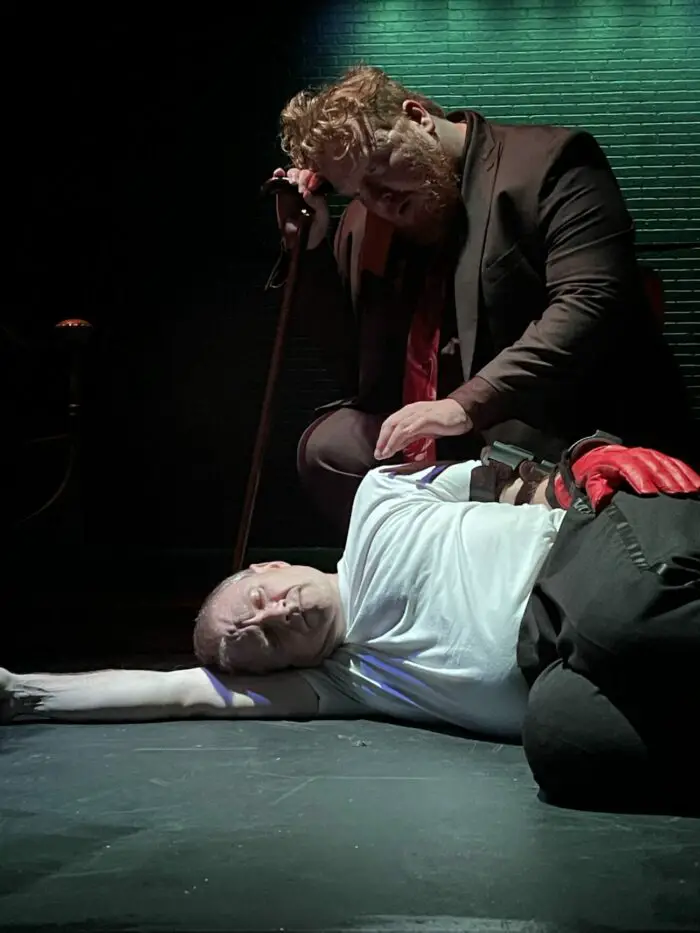

I pondered this interpretive dilemma in the summer and fall of 2022 when I directed a production of Richard III for a theatre company called Sweet Tea Shakespeare in Raleigh, North Carolina. As a teacher of gothic literature, and having directed other spooky shows at my university, I was excited about the dramatic possibilities of this scene. I even devoted a large part of the audition process to letting the actors experiment with “ghost voices” to anticipate what kind of sound we would ultimately get on that undead chorus: “Despair and die.” Once we put the show on its feet, however, I discovered the problem that I have been articulating in this paper: Richard’s ghosts simply don’t do what today’s audiences want them to do.

In conversations with the actor who played Richard, I developed a way to stage the ghost scene that did not significantly change the words of the text but allowed the ghosts to affect the audience’s understanding of the storyline in a way that is more in line with contemporary understandings of hauntings. We did this by physicalizing the concept of “despair” and changing the beginning of the play to anticipate Richard’s haunted self-analysis some two hours before the ghosts appear.

The most important part to me was for the line “despair and die” to become a chorus, an inevitable refrain that the audience knows is coming. Several of the lesser ghosts were cut out of the scene, either because they had been cut from the entire play or because they represented characters who died in Shakespeare’s prequel plays about Henry VI; this left me with a faster-paced, tighter group of six actors who the audience would immediately recognize and who represented distinct physical types.

Then, I asked that question that all tellers of ghost stories must eventually ask: are these ghosts physically present? In some movies, such as Ghost Story, Gotham, and Haunted, people have fully-realized sexual encounters with ghosts, so modern audiences will accept the idea that, at least in the abstract, ghosts can have physical bodies. I decided that these ghosts could invade Richard’s personal space but could not touch him. Each actor playing a ghost was given a slightly different physical relationship with the sleeping Richard; some stood aloof and apart from him, while those who were closest to him in life (his wife, his brother, and his most loyal henchman) mimed specific acts of touching that they could not complete. The effect was to move the ghosts’ emphasis away from judgment toward dread: today’s audiences fear the ghosts not for what they tell us but for what they might do to us. We “despair” in the presence of ghosts precisely because, unlike Elizabethan audiences, we do not believe in them and have no philosophical structure by which to accept their closeness.

Then I made a fundamental change in how the play is structured:

Richard III’s opening line is one of Shakespeare’s most famous: “Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this son of York.” To surprise the audience, we started our production instead with Richard waking up from his ghostly visit in Act V and ruminating on his sins. Thus, instead of his haunting being the end of his story we made it the beginning—after a brief blackout the show “restarted” with the famous opening lines, in effect making the entire play a flashback prompted by the ghostly visit rather than leading up to it. Richard’s dramatic first word “now” becomes in this telling, not the beginning of the story but the beginning of Richard’s confrontation with the story; his guilt is not the result of his evil acts but our way into them. The ghosts themselves appear at the end of the play, but their impact on Richard’s psyche becomes now the very reason for the entire play to happen.

In my opinion as both the director of this production and a “professional” student of ghost stories, this change in emphasis remains true to Shakespeare’s vision of ghosts and also gives modern audiences what we want from them. While the character of Richard III might not feel guilt the same way we do, the process of being haunted still evokes for him the feeling of being judged by a higher power, and it reminds us in the audience of at least the possibility of justice sought in conversations between the suffering living and the unquiet dead. These ghosts speak for Richard’s pre-Freudian conscience, but they also create the need for storytelling as our contemporary ghosts must do. They are both philosophical and tangible, imaginary and visible.

If we aren’t careful, they just might touch us.

References

- Briggs, Julia. “The Ghost Story.” A Companion to the Gothic, edited by David Punter, 122-131. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 2000.

- Botting, Fred. Gothic. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Shakespeare, William. The Norton Shakespeare. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

- King, Stephen. Stephen King’s Danse Macabre. New York: Berkley, 1981.

- Shortslef, Emily. “‘A Thousand Several Tongues’: The Drama of Conscience and the Complaint of the Other in Shakespeare’s Richard III.” Exemplaria 29, no. 2 (2017): 118-135.