Sometimes Loose is Better

In a previous article comparing Stephen King’s novel The Shining and Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of it, I made only a couple passing references to the 1997 ABC miniseries Stephen King’s The Shining. As the miniseries was not the focus of the article, I decided against discussing it at any great length. I will cop to throwing some shade its way in the form of digs at both its subpar visuals (to put it politely), as well as its ham-fisted “correcting” of the Kubrick film’s “Wendy problem”—a problem, as I noted, that exists solely in King’s mind. However, I did not take the additional step of weaponizing the dubious quality of the miniseries in order to bolster the case for Kubrick’s film over King’s novel.

The logic in doing so would, of course, be that if the miniseries represents a true adaptation of King’s novel—opposed to Kubrick’s very loose one—then we need only compare the miniseries and film to conclude that Kubrick was absolutely right to make the changes he did. Not doing so would have resulted in an underwhelming, forgettable, even unintentionally hilarious film. After years of vocal complaining from King about Kubrick’s film and his proclamations that the miniseries would serve as a sort of corrective to the wayward Kubrick adaptation, it’s tempting to take this route. Indeed, the spectacular way in which the miniseries largely falls flat on its face seems to offer concrete evidence that perhaps King is in no position to be judging the quality of anyone’s adaptation…of anything.

Teamwork Makes the Dream Work?

This, of course, is flawed reasoning. Just because a mediocre miniseries is what we got, it didn’t have to be that way. So, what if things had gone differently? What if, back in the late 70s after the success of King’s third novel The Shining, a director other than Kubrick had taken on the task of adapting it for the screen? Perhaps a director more interested in retaining key aspects of King’s novel; one who would work with King, providing insights and expertise on the cinematic end of things while allowing King more control of the storytelling elements as he worked to adapt his own novel into a screenplay.

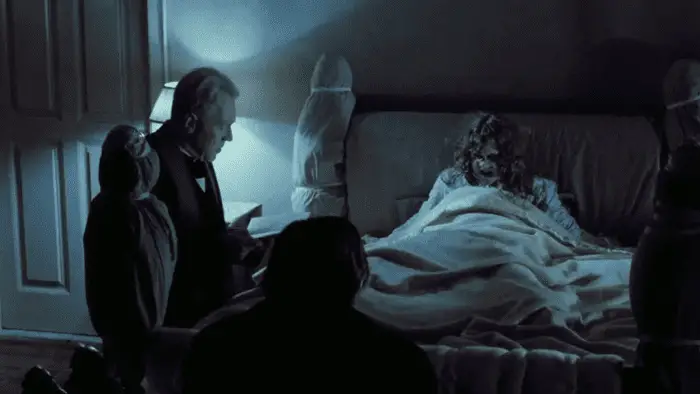

Such a scenario would be much like something that did happen earlier in the decade, when an acclaimed director worked closely with a bestselling author to turn the latter’s novel into a film that was wildly successful both commercially and artistically. When William Friedkin and William Peter Blatty worked together they wound up creating one of the greatest horror films of all time; The Exorcist (1973) is a masterpiece that manages to surpass its source material while still being largely faithful to it. So, what if William Friedkin had decided—in the hope that perhaps lightning would strike twice—to again adapt an enormously popular work of supernatural horror fiction? What if Friedkin had directed The Shining?

William “The Auteur” Friedkin vs. Mick “The Journeyman” Garris

To state the rather obvious, a film directed by Friedkin and released in 1980 would have been vastly different from the 1997 Mick Garris miniseries. Aside from the obvious differences pertaining to era and format, there is the more significant difference between each director’s approach to filmmaking. Garris is the definition of a workmanlike director. His is largely a style without style (notably, King is by his own admission a writer who similarly places relatively little emphasis on style). Garris’s direction isn’t flashy or interesting or innovative; it’s simple, straightforward, and nondescript. This unobtrusive, accommodating approach that he brought to the miniseries allowed for the most literal, wholesale transposal of novel to screen possible. And I think this is probably what King wanted all along: an adaptation in its purest, unmitigated form of his most personal novel.

As I noted in the previous article on this topic, the problem with this is that while King is a pretty good storyteller, his understanding of film as a visual medium seems to range from surface-level at best to severely deficient at worst. As a result, King’s adaptation is faithful to a fault and is also mostly lifeless, uninspired, and dull. Of course, anyone who has both read Blatty’s The Exorcist and seen Friedkin’s film knows that in the right hands an adaptation can manage to be largely faithful to its source material and still be compelling in its own right. In the case of The Exorcist, rather than being slavishly devoted to the source material, Friedkin wisely chose to work with Blatty to find what elements of the novel would and wouldn’t work for the film. The result is a visually interesting, exciting, cinematic version of Blatty’s story. And without a doubt, it is still very much Blatty’s story; but it is equally Friedkin’s film.

In the case of the Shining miniseries, this didn’t happen; instead, Garris was perfectly happy to take King’s input as gospel and not to interfere with King’s extremely literal vision for the miniseries. As a result, King’s adaptation is filled with overly long stretches of less than compelling dialogue, a surplus of exposition, and comically bad visuals that aren’t remotely scary. To that last point, while the bad CGI certainly didn’t help, it’s doubtful whether even “good” CGI would have made a killer fire hose into the stuff of nightmares. Again, compare this with Friedkin’s adaptation of The Exorcist and the difference could not be clearer. The Exorcist is a film in which story and style matter, in which Blatty’s and Friedkin’s strengths in their respective fields are deftly balanced; as a result the film is engaging—and, of course, frightening—both in its content and its execution.

So, imagine what might have been had Friedkin and King collaborated on adapting The Shining. With King working from his own novel, the basic ingredients—the supernatural horrors and the character-driven, psychological elements—would be there. The miniseries, of course, had this piece of the puzzle in abundance; what it lacked was a director like Friedkin with the vision and ambition to shape these basic ingredients into something both narratively compelling and aesthetically satisfying.

Stanley Kubrick: Most Kubrickian Director Ever?

While there are, of course, other directors we might consider (Nicolas Roeg, perhaps?), I think Friedkin absolutely makes the most sense and is the most intriguing possibility for this thought experiment in which we try to imagine a non-Kubrickian, Garris-free adaptation of The Shining. The fact is that no matter who we replace Kubrick with, the result would have been vastly different. Whether you like Kubrick’s style or not, there is no denying its uniqueness; you immediately recognize it when you see it and it would be very difficult to confuse it with any other filmmaker’s. As such, any hypothetical The Shining—even one helmed by an auteur like Friedkin—would bear little to no resemblance to the Kubrick film. If there is any doubt of this, one need only compare The Exorcist and The Shining; while each is a masterpiece not only of horror but of filmmaking generally, they are distinctly different films. No doubt, they have things in common: disturbing visuals, a growing sense of dread, visceral performances. But, for all these similarities, there are as many if not more differences.

What’s Cooler Than Being Cool? Ice Cold!

The Shining is a famously cold film. Visually, it is full of intimidatingly large, open spaces. Spaces that feel unwelcoming and that dwarf the people in them. These spaces are rendered even more uncanny through the film’s cinematography; at times the camera moves almost surreptitiously, at other times boldly as if through sheer force of will or else by some mysterious, external compulsion. The spaces are often bathed in bright, hard light that only accentuates their vastness and gives them an unsettling, almost sterile quality. The score and sound design match the visuals by creating an ominous soundscape full of low drones, dissonant chords, and sudden atonal blasts of sound.

At all times, The Shining is a film that looks, sounds and feels tightly composed, even controlled—which, of course, it is. This sense of control and orchestration does give the film an air of detachment, with many scenes playing out more like theatrical, even operatic tableaux than naturalistic slices of life. And, of course, this slightly off, unnatural quality is something many people point to when discussing the film (and other Kubrick films, for that matter).

For some, this unnaturalness is a flaw; for others it only adds to the film’s effectiveness. Specifically, it contributes to the overarching feeling that the events of the film are, in a sense, preordained. It’s fair to say that casting the film’s events in this light does somewhat diminish the film’s human elements, particularly the agency of its characters. Notably, Stephen King once criticized the film for feeling as if it were fundamentally disinterested in its human characters—who they are, what they do, what happens to them. He likened it to someone—Kubrick, in this case—looking down dispassionately at ants crawling on the ground. And, truthfully, King isn’t entirely wrong in his assessment; it’s a fair critique. But whether it works for you or not is, of course, a matter of personal taste.

The (Relative) Warmth and Fuzziness of The Exorcist

With the exception of its use of both score and ambient sound to generate a sense of dread, The Exorcist shares few of these qualities of The Shining. In spite of the increasingly fantastic nature of the film’s events, it always manages to feel squarely grounded in reality, a testament to Friedkin’s masterful control of tone, as well as the actors’ understated performances (Kubrick’s control in The Shining is just as impressive, but he is working toward a very different end). Where The Shining is big and impersonal, The Exorcist feels much smaller and more intimate. If anything, in The Exorcist, space feels almost contracted; most of the events take place within the confines of a modest-sized townhouse, and often within a single room. Characters are often in close proximity to one another and—through the film’s frequent use of close-ups—to us in the audience, which nicely complements the aforementioned understated quality of the performances.

The Exorcist does, like The Shining, feature many scenes that are brightly lit, including many daytime scenes (which was, and still is, unusual for a horror film). However, in The Shining the appearance of natural light was often achieved by artificial means; e.g., by using a multitude of powerful lights outside the massive windows of the Overlook set to simulate the almost blinding white glare of sunlight on a snow-covered mountain landscape. In contrast, The Exorcist makes frequent use of actual natural light. As a result, where The Shining gives off a distinct—albeit hard to describe—feeling of the unreal trying to mimic what is real, The Exorcist does not. And it is difficult to overstate just how far the appearance of reality can go in making a film feel more real.

The Shining, of course, is never particularly interested in conveying a sense of reality, and that works for the film. In The Exorcist, the feeling of reality is key as it helps immeasurably to render the film’s supernatural content more effective—especially for nonbelievers. The Shining is exceedingly effective largely because it eschews naturalism in favor of the disorienting, disconcerting, and surreal aura of a twisted fairy tale; The Exorcist, on the other hand, largely succeeds in being as unnerving and disturbing as it is because of its carefully cultivated sense of verisimilitude.

It’s a safe assumption that Friedkin would have brought a similar grounded-in-reality approach to The Shining; such an approach might have worked very well, particularly for a more faithful adaptation of the novel, which would entail a great deal more of the fantastical (think topiary animals) than the Kubrick film did. If Friedkin’s vérité style worked for 360° head spins, levitating and projectile vomiting, then perhaps he could have succeeded where Garris failed and where Kubrick thought better than to try.

The New Mr. and Mrs. Torrance?

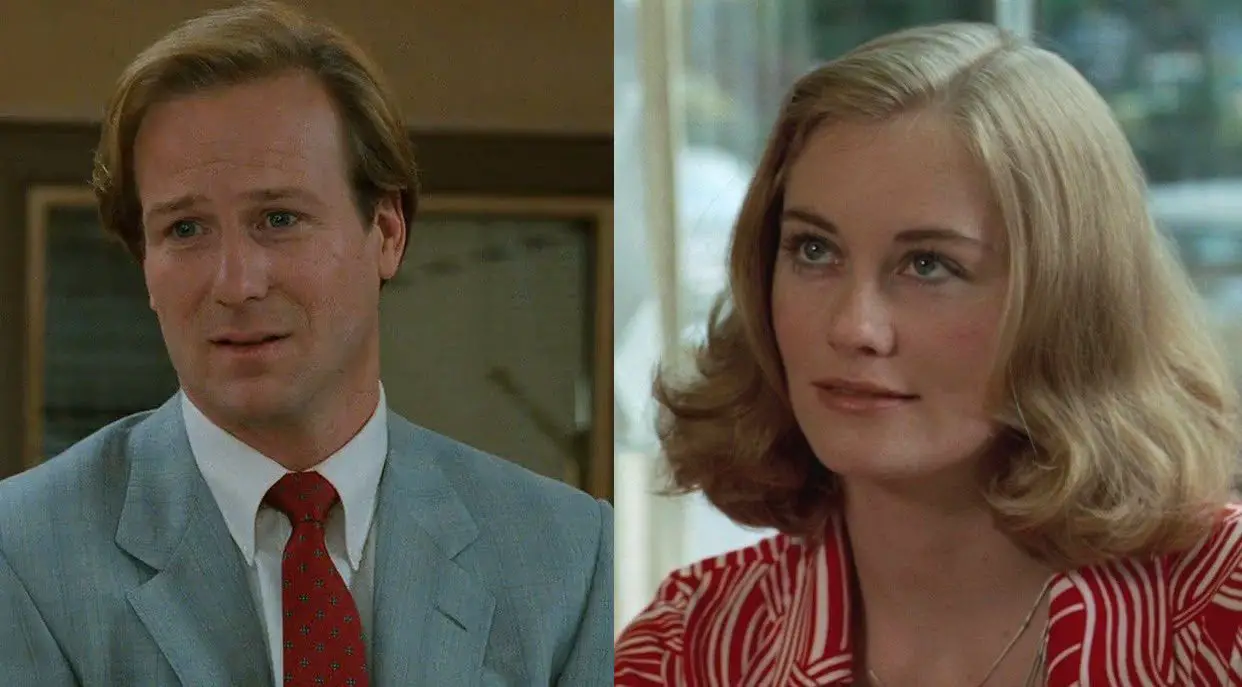

While we’re discussing things Friedkin would have done differently, we can’t overlook (sorry) the issue of casting. If there is one specific element of Kubrick’s film that people—including King— criticize, it’s Jack Nicholson’s performance. As noted, The Exorcist features some excellent, understated performances; Nicholson’s performance, while still excellent, is certainly anything but understated. So, while we’re reimagining things, let’s go a step further. Since swapping out Kubrick for Friedkin almost certainly means swapping out Nicholson—a characteristically idiosyncratic and controversial choice on Kubrick’s part—let’s suppose the role of Jack is recast. Who would play him? Among the actors King is on record saying he would have preferred for the role of Jack are Jon Voight, Christopher Reeve, and Michael Moriarty. I agree that any one of these actors would have been more than capable of playing the role of Jack Torrance as depicted in King’s novel. That is, a flawed but essentially likeable and relatable “regular guy” trying to do the best for his family while simultaneously battling alcoholism and pesky, murderous ghosts. In the interest of keeping things fresh, I would like to offer my own suggestion for another actor I feel could have filled the role: William Hurt.

While we’re at it, since Shelley Duvall was also a Kubrick choice and Kubrick in this hypothetical scenario is quite literally out of the picture, let’s also recast the role of Wendy (this also makes sense given the fact that Duvall’s performance gets only slightly less grief than Nicholson’s—quite unfairly, I think). There are certainly a number of actresses who would have made sense for the role; I’ll suggest one of the first that comes to mind and say Cybill Shepherd. Hurt and Shepherd would both have had the dramatic chops for the roles and would have been convincing as a “typical” young couple, though of course a particularly photogenic one. They also would have been about the same age (around 30 years old in 1980) and would have been believable as parents of a five-year old.

An additional benefit of casting Hurt would have been his anonymity; his first film role was in Altered States, another—albeit very different—horror film released in 1980, the same year as The Shining. This would, of course, have eliminated any potential issues related to preexisting audience perceptions—one of King’s biggest complaints regarding the casting of Nicholson. As for Shepherd, while she was known, she wasn’t exactly a star; she would become a much bigger one later in the decade (and into the next) for her starring roles in the TV shows Moonlighting and Cybill. In 1980, most audiences would probably have known her best for her role as the object of the unhinged Travis Bickle’s unrequited desires in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976). And while Travis Bickle and Jack Torrance are certainly very different characters, perhaps Shepherd in the role of Wendy may have been able to draw on her experience playing a woman dealing with another deranged and dangerous man.

With these further changes made, it starts to become easier to envision our hypothetical The Shining: Friedkin’s realistic and naturalistic style accompanied by his eye for detail and penchant for compelling imagery; Hurt and Shepherd delivering powerful but understated performances in the lead roles. Imagine Hurt playing Jack as an Everyman struggling with alcoholism and feelings of inadequacy, perhaps a performance not unlike Jason Miller’s as a priest struggling with a crisis of faith; imagine Shepherd channeling the same energy as Ellen Burstyn to convey both a cool confidence and the quietly growing desperation of a mother terrified for her child, a desperation that finally explodes in rage and fear. Taking these changes into account, we begin to see how this version of The Shining would have been far truer to the novel King wrote, while still remaining more than simply a carbon copy of it.

In Theory, a Friedkin Adaptation Works…In Theory

No doubt, this speculative The Shining would have been dramatically different from, though not necessarily better than Kubrick’s film; it also would have been significantly better than the miniseries. Nevertheless, I’m glad that we didn’t get a Friedkin adaptation of The Shining. While it’s a fascinating possibility to consider, as is often the case, I think that ultimately it’s probably more satisfying as a hypothetical abstraction than as the real thing. I have no doubt that an adaptation of The Shining directed by Friedkin would have been good, potentially even great; but, at the same time, I doubt it would be the strangely beautiful (and beautifully strange) film that Kubrick’s is. A possible, even likely, best-case scenario is that it would be a lot like The Exorcist; but, as much as I love The Exorcist, I’m not sure that’s the version of The Shining I want. Since The Exorcist already exists, we really don’t need another film like it.

A not quite worst-case scenario (I think the miniseries has a strong claim to that distinction) is that it might have turned out as a classier, more sophisticated The Omen or The Amityville Horror; in other words a more or less conventional—albeit artier—horror film. That wouldn’t be a bad thing per se; the problem, for me, is that I can’t pretend that the Kubrick version doesn’t exist. And the Kubrick film, whatever you think of it, is decidedly unconventional; indeed, it is a film as fascinating for what it isn’t (a typical horror film, a good adaptation) as for what it is—namely a masterpiece of filmmaking.

Beef à la King

But, while I’m thankful for the choices Kubrick made in adapting The Shining, I can at the same time understand why King and many fans of the novel dislike Kubrick’s film. I can also understand why, for some, speculating about what an adaptation of The Shining might have been is probably bittersweet—and perhaps more bitter than sweet. While imagining the possibilities might be exciting, it might also stoke feelings of resentment over an opportunity wasted. The truth is King’s novel probably did deserve better than what it got. It’s fair to say that the legacy of its adaptations has probably—to some degree at least—both irreparably obscured the intrinsic worth of King’s novel as well as tainted our collective perception of it. It has largely been overshadowed, first by a great film that gutted the source material and then by a faithful but thoroughly mediocre miniseries (though I’ll call that one a self-inflicted injury). Aside from sheer curiosity then, I suppose what almost makes me wish we had gotten a Friedkin version of The Shining is—at the risk of sounding perhaps just a bit melodramatic—a sense of some unredressed injustice.

Alas, sometimes that is just—as they say—how it goes. And, hey, there’s always the many, many other King adaptations, most of which are largely faithful to their source material and some of which are even good. So, perhaps the fact that we never got an adaptation of The Shining that was both true to the novel and—you know—good isn’t so terrible after all. Obviously, if you love the Kubrick film, this is an easier pill to swallow; but, even if you don’t—even if you hate it—if it didn’t exist wouldn’t some part of you miss all the wonderful arguing it’s given rise to lo these many years? The spectacle—unfolding largely in the comments sections of myriad articles across the internet—of the insufferably pompous and the profoundly butthurt duking it out as if their very lives depended on it?

But, in seriousness, all this rancor between King fanboys and Kubrick stans (Stanleys?) is unnecessary and, frankly, a bit absurd. Love what you love, hate what you hate; that’s what I always say (at least it’s what I’m saying right now). But don’t insist other people feel the same way or go all Jack Torrance when they don’t. In the end, when it comes to The Shining, all of us—Stephen King and his fans, Stanley Kubrick and his fans, Mick Garris and his fans—turned out okay. And that is a happy ending worthy of King himself.