Sequelitis: Not a Gum Disease but Very Much Ever-Present

The concept of the sequel is one that belongs almost entirely to the world of film. It’s true that television and written fiction have their equivalents—spinoffs and book series, respectively—but the sequel in its purest form is a distinctly cinematic phenomenon. And what is that “purest form”? Simply put—a cash grab. Of course, there are exceptions to the rule, sequels that are genuine and organic continuations of a larger narrative set into motion by the original film (e.g., The Godfather Part II, The Empire Strikes Back, Paul Blart: Mall Cop 2). But the vast majority of sequels, even those that occasionally manage to be decent films in their own right, feel neither necessary nor narratively justified.

I would like to point out here that I’m not naïve; I understand that moviemaking is a business. For that matter, I understand that sequels don’t have a monopoly on the profit motive, while originals are all about the art; I understand that all commercial films are intended to make money. I am, perhaps, just naïve enough to often give filmmakers the benefit of the doubt when it comes to their films. In other words, I believe—at the risk of sounding clichéd—that they genuinely had a story, a vision, or both that they wanted to share with the world and that that was their primary motivation rather than the almighty dollar.

Interestingly, despite the utter transparency of profit’s role in sequels, more often than not there is an effort to maintain the pretense that this is not the case. Everyone from studio heads to directors, screenwriters, and actors will tout some variation on “There was more of this story to tell.” It’s why I actually find those rare instances when this doesn’t happen so refreshing. I have more respect for the people involved in making a sequel when they forego the charade, the putting on airs about “creative vision” or “the art of storytelling,” and are simply upfront about the fact that the thinking behind most sequels rarely goes beyond something to the effect of “Hey, Movie X was moderately successful, let’s do that again.”

As Usual, We Could All Learn a Lot from Friday the 13th

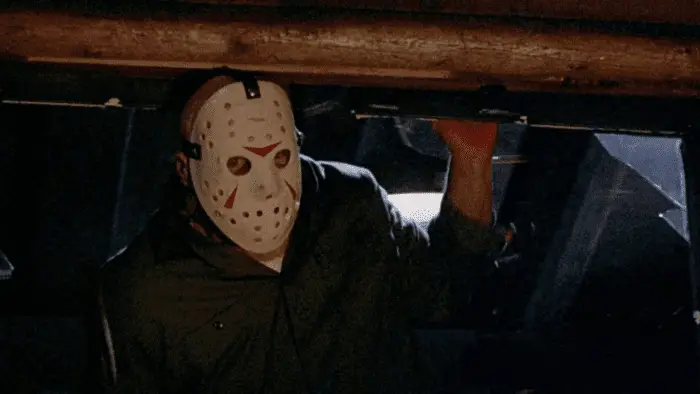

Alas, it’s exceedingly rare to hear anyone in Hollywood speak with any kind of candor about sequels. Apparently, no one—even the most blatantly crass, profit-driven Hollywood crap peddler—wants to be seen as a blatantly crass, profit-driven Hollywood crap peddler. I feel like it wasn’t always this way; an example that immediately springs to mind is the Friday the 13th franchise, particularly during its 1980s heyday. Neither Paramount nor any of the cast or crew involved ever tried to pretend the series was anything other than what it was (i.e., mindless, popcorn entertainment). In fact, there is a certain purity to the series’ approach to sequels.

As I noted in my article on Friday the 13th Part 2, the Friday films are essentially iterations; they repeat, nearly unchanged, a formula from one entry to another. They are continuation as reenactment, rather than development. Whatever you think of the films themselves, there is something admirable in how boldly they strip away the pretense of the sequel as a creative endeavor, leaving exposed the reality of the sequel as a mercenary and calculated play for audiences’ hard-earned dollars. Really, what bothers me about sequels isn’t so much that they are largely cynical and artless, rather it’s that they are often so comically disingenuous about why they exist at all.

Scare Me Once? Good On You. Scare Me Twice? The @#$! Is Wrong With Me?

As a fan of horror films, sequels come with the territory; perhaps more than any other genre, horror is one in which the specter of the sequel is nearly ever-present. Some of the most well-known films within the genre are those that have spawned seemingly interminable sequels. Now, just generally, the ratio of good to bad films is wildly disproportionate, and the ratio of good to bad horror films is seemingly astronomical. On top of this, the ratio of good to bad sequels is even more wildly disproportionate. So, the ratio of good to bad horror sequels? If you guessed “even more wildly astronomical,” you are correct. What is perhaps the single worst thing about horror sequels—and I think this is something that is almost unique to the genre—is that not only do they nearly always fail to live up to their predecessors, often they actively threaten to undermine most (if not all) of what was so effective the first time around. This effect seems to increase exponentially as the number of sequels—each more unnecessary than the last—increases.

While no sequel (or even series of sequels), no matter how misguided, ill-conceived, or inane, can destroy the legacy of a truly great original, they can have the effect of somehow retroactively cheapening that original by reducing it to merely a first installment, rather than a stand-alone, self-contained artistic expression (if you’ll permit me the mot douche). With the “spawning” of a series or franchise (and what a weird, gross expression that is), those cinematic offspring—no matter how illegitimate, inbred, or bastardized they are—become inescapably part of the original’s legacy. And the more inspired, brilliant, or innovative an original film is, the sadder that is.

One reason I believe that horror sequels in particular are so often woefully inept, pale imitations of the originals that precede them is that horror as a genre is an intensely, even viscerally effective one (comedy is perhaps its only rival in this regard). One might say that horror is largely driven by the effect (or effects) that it produces in its audience (indeed, the very name “horror” denotes a response). And thus, we might say that the most effective horror films are those that engender the most pronounced affective response in the viewer. When it comes to horror films, much of the ability to elicit the desired response of “horror” depends largely on there being at least some degree of novelty to the horrors presented. I would note that “horror” is a response that covers a fairly broad range; for simplicity, we can say that it entails everything from disgust to discomfort to dread and everything else in between. Unsurprisingly, this is much easier to do the first time around; thus, originals—especially those that are, in fact, original—have an inherent advantage over sequels.

As so much of the capacity to frighten or horrify relies on unfamiliarity, uncanniness, and inscrutability, the more that horror films mine the same material for their scares, the higher the chance for diminishing returns. This is why horror sequels so often feel the need to up the ante. More often than not this results in a rampant gratuitousness—usually of sex, nudity, violence, and gore—but often of storylines, background information, character motivations, and worldbuilding as well. All of this excess rarely makes for more effective horror. In fact, this tendency toward overkill—a particularly apt term in this case—frequently dilutes the distilled potency of the original films, marring what once had a certain elegant simplicity with so much clutter.

Indeed, the very simplicity of some horror films has much to do with why they succeed to the extent they do. Many of the best horror films of all time share a certain primal, elemental quality. For example, the original Halloween and—perhaps the example par excellence—The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (I would include as well, albeit to a lesser degree, the original A Nightmare on Elm St.). Famously, over the past several decades all three of these films have been subject to an onslaught of sequels, prequels, and remakes. While there is, no doubt, a sharp distinction in quality amongst these films, I will—with confidence—maintain that not one of them really needs to exist.

Trick or Treated to Death

In the case of Halloween, over the course of 43 years and nine (soon to be 10 and eventually 11…ugh) return visits to Haddonfield and the Michael Myers saga, there have been exactly zero (0) films that have been even a patch on the original. This includes the much-ballyhooed 2018 sequel, a technically well-made bit of fan service that should have been called Halloween H40. One, this would have avoided the utter inanity of giving a sequel the same title as the original (resulting in three films all called Halloween…once again, ugh). Second, it would acknowledge the film’s bold approach of essentially retelling a story already told 20 years earlier in Halloween H20. Impressively, it did this whilst also getting many people to believe that this sort of twice-told tales repackaging somehow qualifies as a big deal. That it did so in part by selling itself as some kind of #metoo, #timesup-aligned bit of wokeness is particularly laughable, but also pretty gross.

For me, the Michael Myers “story” ends at the conclusion of the first film; he is alive, and he is out there, somewhere in the darkness. When and where will he strike next? That question is the appropriate closing punctuation. To answer the question—over and over and over again, no less—is to extend a perfectly good sentence—clear, concise, and powerful—into a bloated run-on. Such long-windedness takes up undue space on the page by adding words but not meaning and runs the risk of obscuring the beauty of the original statement amidst all the bollocks.

First As Tragedy, Then As Farce

Unlike the Halloween franchise, which continues to labor under the delusion that it is an even marginally serious film series, the Nightmare on Elm St. franchise went in a very different direction. Until the return of Wes Craven and the self-seriousness that came with his involvement, the Nightmare series leaned into the inherently fantastical nature of its premise by becoming increasingly outlandish—even cartoonish—with each sequel. Famously, Freddy Krueger became—in addition to a killing machine—a joke machine, incessantly spouting one-liners and bad puns in between show-stopping, set-piece murders.

Partly, this was a natural outgrowth of the films’ central conceit that Freddy is a killer who inhabits the highly illogical and protean world of dreams; as such, it made sense when wackiness ensued. Second, with regard to the humor, the seed of this is planted in the original film; Freddy shows glimpses of dark humor, though he is not yet the standup comedian of later entries (what happens with Freddy’s character could in fact be seen as an example of the phenomenon known as Flanderization). Third, it is also conceivable that the people behind the Nightmare sequels—the studios, writers, and directors—intuitively understood that horror sequels, while offering the potential for massive profit, also tend to reduce the potential for actual horror. Accordingly, they may have decided to sidestep the problem by moving away from more overt horror and toward something more akin to horror-comedy. Though I wouldn’t classify the later, pre-New Nightmare sequels as full-on horror-comedy, they are nonetheless clearly aimed more at being entertaining and fun—something they arguably achieved only fitfully and increasingly less as the series ground on—than the stuff of actual nightmares.

More Than One Way to Skin a Dead Horse

I alluded to the original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre as being perhaps the quintessential example of the horror film as a primal, elemental, visceral force of nature; of storytelling stripped to its bare bones in order to deliver a uniquely affecting experience. It is the horror film as implement—sword, scalpel, and cudgel in one (a sadistic Swiss Army knife of sorts). If ever there were a horror film in need of no follow-up—and that most do not is, of course, the entire thrust of this article—it is The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. It is such a singular achievement, one so perfectly realized, that the very idea of adding on to it is almost enough to bring on a fit of uncontrollable laughter as one rides off in the back of a pick-up truck while a portly, formalwear-clad madman gives chase.

And yet—between direct sequels, remakes, sequels to remakes, prequels to remakes, and “re-imaginings”—there have been to date no fewer than seven Texas Chainsaw films (even saying that induces a slight shudder and not the good kind). To say, as I did of the umpteen Halloween retreads, that none of these comes close to the original is a Texas-sized understatement. And I say this as someone with not only a certain appreciation of the utterly batshit 180˚ that is The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 but even a slight fondness for the 2003 remake. However, I consider both as their own self-contained, discrete entities with no connection to the original film; in fact, I cannot conceive of them otherwise. That said, if neither ever existed or if somehow both were magically erased from the collective consciousness, I suspect the impact—both personally and for the genre as a whole—would be negligible to nonexistent. This is the absolute last thing I could say about the original; on the other hand, for some of the other entries in this distended franchise—those which longingly cast their eyes up toward mediocrity—such a statement of mere indifference might be considered minor praise.

From Excellent to Excrement

Of course, I would say the same for most of the entries in the Halloween and Nightmare on Elm St. series—and indeed for the majority of horror sequels. The Texas Chainsaw franchise, by virtue of being so egregiously bad, is simply the most salient example of crass “sequelization”: a grim and undignified process in which an intellectual property either cannibalizes itself or else is slowly devoured by opportunistic and creatively bankrupt jackals. Ultimately, whether the damage done is self-inflicted or not, the end result of such contemptible consumption is eminently predictable; eventually, after any meal—irrespective of quality—there comes the inevitable bowel movement.