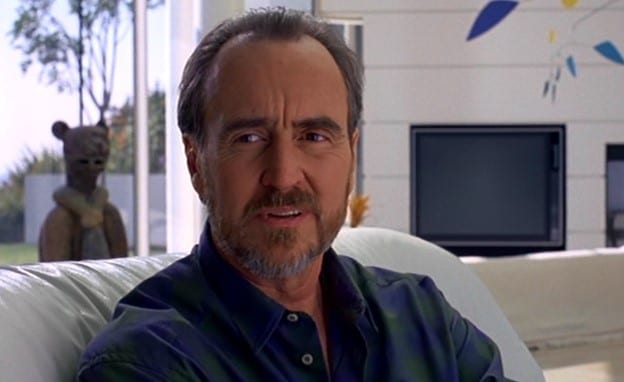

Author Note: This article is not intended as a personal attack on Wes Craven. I respect his contributions to the horror genre, regardless of how I feel about the dubious thematic content (and yes, quality) of some of his work. And, from all accounts, he was a perfectly lovely guy. All this to say: this is intended merely as a take—and not a hot one, at that—on three of the most notable films from one of the genre’s most important filmmakers.

The Trouble with Wesley

I’d like to talk about a problem I have with Wes Craven, or rather a problem I have with three of his films: The Last House on the Left, The Hills Have Eyes, and A Nightmare on Elm Street. All three films center on vengeance (specifically, violent vengeance) and what happens to those who seek it. In The Last House on the Left and A Nightmare on Elm Street, it is the vengeance of parents on their children’s murderers; in The Hills Have Eyes, it is the vengeance of surviving family members on the killers of their loved ones. Each film not so subtly suggests that, by violently avenging these deaths, the “innocent” victims become just as guilty as those whom they sought vengeance against, and that, ultimately, vengeance is their undoing (if not literally, then certainly spiritually). I have a problem with this message. It strikes me as facile and glib, for one. It also comes off as pretentious, self-righteous, and sanctimonious. The fact that Craven came back to this idea three times makes it clear that this was a message he felt compelled to convey. I can only imagine that he saw it as a very noble, very moral, and very enlightened message; however, I’m not so sure it’s any of those things. I think it’s more naïve and tone-deaf than anything else; it is, in fact, moral equivalence, plain and simple. It’s an oversimplified and overly judgmental worldview that, while ostensibly rooted in secular humanism, nevertheless reeks of the kind of moral absolutism usually associated with religious fundamentalism (which makes me wonder if perhaps some residue of Craven’s strict Christian fundamentalist upbringing was at play).

On a High Horse, Tilting at Windmills

It’s easy to take such a detached view, one that ignores the realities and exigencies of real-life and of the human condition, when one is approaching matters from a purely philosophical or academic perspective. Such a perspective seeks to be “above the fray”, so to speak; the problem with being “above the fray”, or wishing to be, at any rate, is that it usually entails mounting yourself firmly upon your high horse. No doubt, Craven believed he was making important and meaningful statements about the futility and moral emptiness of violence by offering blanket condemnations of all acts of violence. In such a worldview, all instances of violence are necessarily and absolutely equal, regardless of things like context. The “message” of these films strikes me not as profound and insightful social commentary, but rather as smug and preachy pseudo-philosophy. While you may not be able to see Craven’s high horse when you watch these films, you can nonetheless smell the horsesh*t from several miles away.

It’s NOT Only a Movie, Apparently

Though each film deals with essentially the same idea, that of vengeance as a double-edged sword, it’s helpful to consider each on its own merits (or lack thereof). In The Last House on the Left, the parents don’t even go out seeking the killers, the killers come to them. So, we have two parents who have just found out that the people who brutally raped and murdered their daughter are in their house and we’re supposed to pass judgement on them for being too extreme in their response? The one criticism I would make of their response is that it is utterly unrealistic; these are not the actions of genuinely traumatized human beings but rather cartoonish exaggerations that turn grieving parents into implausible vengeance-machines. Useful, I suppose, for illustrating Craven’s “point” about the degrading effects of violence but not much else. Certainly not for contributing in any way to even a quasi-realistic portrait of trauma. All well and good for a simple exploitation flick but, of course, Craven would go on to claim that The Last House on the Left was “more” than that, that it was, in fact, serious social commentary. With this claim, for me at least, Craven invites further scrutiny of the film.

However, let us put aside the question of why exactly the parents enact their revenge in such a uniquely grindhouse film manner (aside from the fact that The Last House on the Left was, you know, a grindhouse film). Let us consider only the fact of the vengeance itself and not the particular forms it takes. Not only are the parents avenging their daughter’s death, but they are arguably also defending themselves from extremely dangerous people. Furthermore, they’re probably preventing the suffering of others in the future, especially since the film goes out of its way to show us that the authorities are entirely incompetent and thus would, no doubt, prove largely ineffective in apprehending the merry band of murderers and rapists. And yet, as the final images of the parents—bloody, “victorious” but clearly simultaneously defeated—suggest, we are meant to see a parallel between them and the recently deceased murderers and rapists. This seems especially clear given the visual similarities between these final shots and the earlier moment, after the rape and murder of the two young girls, when we see Krug and company, who heretofore have been depicted as nothing but vicious psychopaths, briefly look…guilty? Regretful? Disappointed? I’m not sure. It’s another example of something that makes little sense and seems to exist only to make the film’s “message” clearer.

One of the Most Bizarre Crimes in the Annals of American History…The Desert In-Law Massacre

In The Hills Have Eyes, we are again meant to see how easily the supposedly civilized can devolve into savagery and how truly awful it is. However, that argument—much like the desert in which the unfortunate family finds themselves at the mercy of a clan of murderous, baby-napping cannibals—simply doesn’t hold water. In this case, the element of self-defense is even clearer than it is in The Last House on the Left. The protagonists in The Hills Have Eyes are viciously attacked, suffer several devastating losses, and then decide to fight back. What were they supposed to do, just sit back and let Papa Jupiter and company kill them? I’m sure that the film’s final image, the young husband killing one of the desert people in a murderous rage (at which point the film ends in a red-saturated freezeframe), is really meant to drive the point home. “Look at what he’s become,” we’re supposed to think. Oh, you mean the guy who’s just saved his baby from becoming dinner for the people who have also killed his wife and his in-laws is a little miffed? No sh*t, huh? Yeah, you’re right Wes Craven, what an a**hole that guy is for stooping to their level. Obviously, you would never do such a thing. I guess as viewers we’re either meant to feel some kind of smug moral superiority or, if not, we’re supposed to feel bad because we’ve had some revelation about our own flawed morality. Well, I don’t feel either of these things; what I do feel is the buzzing of my internal bullsh*t meter.

Meeting of Springwood PTA Erupts into Mob Violence; Local School Janitor, Child Murderer Burned Alive

In A Nightmare 0n Elm Street, Craven further illustrates what happens to those guilty of the deadly sin of wrath. I think it’s important to note here that the acts of vengeance in these films are meant to be seen as sins and not merely as crimes. They are, of course, unquestionably crimes, but I believe Craven sees them as more than that. Crimes are, of course, violations of man’s laws, not of God’s laws; thus, while crimes typically entail punishment, they do not necessarily endanger the transgressor’s very soul, as sin does. The fact that these films make a point of illustrating the impact of vengeance on those who seek it strongly suggests that we are meant to see vengeance as a cause of irreparable spiritual harm, rather than as a crime that may be expiated through worldly punishment. In A Nightmare on Elm Street, this point is made explicit; after all, mere crimes do not typically engender the kind of cosmic comeuppance we see in the film. The fact that the punishment for vengeance, in this case, is particularly biblical (the sins of the father being visited upon the children) lends further credence to this “vengeance as sin” interpretation.

That it is the children of the guilty who must pay the price for their parents’ “sin” of vengeance is especially obnoxious. While the film doesn’t present its teen characters as bad people, it certainly suggests that their parents are. And why, according to Craven, are they bad people? Once again, it’s because they succumbed to vengefulness. In the context of the film, they acted not merely irrationally, even criminally, but immorally (so immorally, in fact, that they have brought doom upon their surviving children in the form of supernatural vengeance from beyond the grave). For Craven, the parents’ grief doesn’t matter; the fact that again, as in The Last House on the Left, it is clear that the authorities are incapable of effecting justice doesn’t matter. In this film, we once again have emotionally wrecked human beings seeking, in a fit of desperation, some modicum of the justice that has been denied in the wake of terrible tragedy; they act illegally but in an eminently human way by taking matters into their own hands. However, in Craven’s view, there is only the sin of vengeance. In The Last House on the Left and The Hills Have Eyes, he stops at the point of merely demonstrating the futility and wrongness of vengeance. In A Nightmare on Elm Street, he takes a step further and shows us the inevitable punishment that is the wage of the vengeful sinner.

Going to the Well AT LEAST Once Too Often

If the idea of vengeance as something that debases those who seek it was one that Craven had turned to once, I might still find it problematic, but I probably wouldn’t bother writing about it. However, the fact that he returned to it two more times makes it harder to ignore; the obtuseness of the message is perhaps equaled only by his persistence in delivering it. I think it’s significant that both his debut and sophomore efforts tell essentially the same story (with the same implications), with only the details changed. Though he would stray from it for a few films, he inevitably came back to it for what would be his most successful film to that point (and still his most successful, after the Scream series). Thus, the three films discussed here are far from blips on the radar in his directorial career, quite the contrary, in fact. These three films are, along with Scream, his most well-known, most discussed, and generally most highly regarded works.

“I Knew George A. Romero and John Carpenter. Wes Craven, You’re No George A. Romero or John Carpenter.”

Putting aside the fact that I find two of the three rather shoddily made, it is the barely concealed subtext of the three films that I find most objectionable and which makes me loath to place Craven alongside other giants of the genre like Carpenter or Romero. While both could be as guilty of ham-fisted moralizing as Craven, I find their brand of moralizing less aloof than Craven’s. In the case of filmmakers like Romero and Carpenter, I can understand the morality behind the moralizing. When Romero or Carpenter lambastes consumer culture or blind obedience to authority, I understand where they’re coming from. But, when Craven equates victims with victimizers in these films, I don’t see the morality. Or rather, I see only the absolute morality of abstract philosophy, a morality divorced from real life as it is lived and experienced by real human beings in the real world. In this sense, I don’t find Craven’s message particularly humanist at all; on the contrary, I find it profoundly anti-humanist—the cold and detached morality of the professional intellectual and academic.

Thanks for this. I felt krugg/Kruger are the same archetype revisited. Interestingly they share the name of the antagonist in Clint Eastwood’s sudden impact. Like the evil dead at the worst Wes cravens krug/kurger a rape clown. Making a joke out of sexual abuse. In sudden impact we get a different type of final girl. There’s an institutional evil too. Perhaps feminism may view as institutionalised patriarchy that creates media that invites the audience to laugh at rape. By placing the violence as a relative idea in the viewer we are asked to compare the light heartedness of a bumbling cop or witty one liner to the eroticism of sadism. This level of self importance continues with ghost face and pinky/shocker. Violence is always there to titlate and entertain as opposed to being functional and unglamorous.