On March 9th, Amazon announced their new limited anthology series, Them, describing the show as: “The 1950s set first season centers on a Black family who moves from North Carolina to an all-white Los Angeles neighborhood during the period known as The Great Migration. The family’s idyllic home becomes ground zero where malevolent forces, next-door and otherworldly, threaten to taunt, ravage and destroy them.” After the company released the trailer on March 22nd, many people were quick to make comparisons between the show’s trailer and the work of comedian-turned-horror-master, Jordan Peele.

Them showcases the horrors faced by the Emory family after moving to Compton in 1953 (accurately portrayed as a predominantly white area). It is an obvious ode to—if not a blatant rip-off of—Peele’s unique filming style. The show had potential and fit in with the trend of using horror to explore very real issues relating to the Black experience in America. However, what makes movies like Peele’s Us, Get Out, and, arguably, Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz’s Antebellum work is their ability to address these issues head-on while using fantastical story elements as a metaphor. Them ventures too close to reality by blatantly exploiting Black history, including redlining and minstrelsy, to create superficial scares geared towards a white audience.

Minstrelsy

Minstrelsy is a purely American form of entertainment, spanning back to the early 19th century. Of course, Thomas ‘Daddy’ Rice’s racist caricature, Jim Crow, is the most famous example (see an engraving of Rice in character here). Jim Crow began as a slave song, likely in the Caribbean and Carolinas. Rice, a native Kentuckian, started as a mediocre circus performer who traveled around the Eastern United States in the 1820s. Reports differ on exactly how he appropriated the song and made the character associated with him, with arguments ranging from a crippled slave teaching Rice the song and dance to a former slave claiming he publicly performed when Rice was an audience member.

Regardless of how Rice learned the song and dance, the moment he smeared burnt cork on his face in the early 1830s, a cultural phenomenon began. Rice soon took a world tour, performing around Europe and Australia, before dying in obscurity in 1860. While he may have died alone and forgotten, Rice’s performance spawned countless imitations, and those seeking live entertainment could see other Jim Crows, Zip C*ons, and Dandy Jims across the United States, making a living caricaturing Black people.

Them features a minstrel character throughout (although he becomes more full-fledged in Episode 8). Instead of a white man in blackface, the creators decided to make Da Tap Dance Man (Jeremiah Birkett) wear heavy grease paint ala Ben Vereen. But while Vereen was making a political statement, Them has opted for an on-the-nose approach that reduces the heinous act of blackface characterization to an attempted horror trope. Instead of relating it to Rice and co. or even a reclamation ala Vereen and the countless Black performers before him, the viewer sees a historical boogieman. This in no way reflects on Birkett (read his interview here), who tries his hardest to give the character some sort of depth, but instead reflects on the writers who have constructed a character as shallow as the series. Viewers instantly understand that Henry Emory (Ashley Thomas) sees aspects of himself in Da Tap Dance Man, but instead of pushing the envelope or thinking outside the box—think Birkett in whiteface—Them features a caricature that is as offensive as what it’s attempting to speak out against.

Redlining

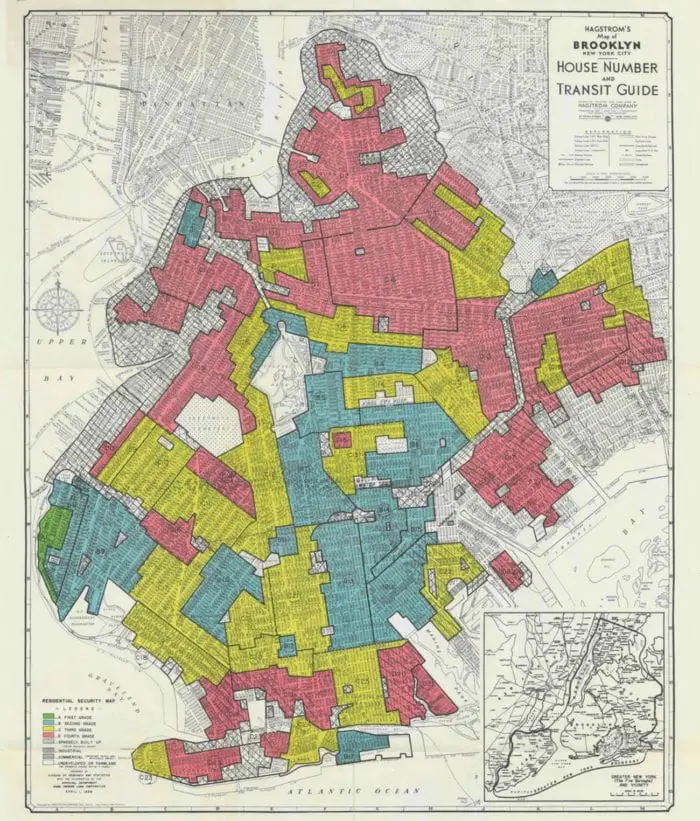

Local governments and housing lenders used redlining to keep people of color, with a focus on African Americans, in certain neighborhoods (colored red on financial risk maps) by refusing them housing loans in the 1930s–1960s. Redlined neighborhoods would in turn be denied certain amenities and services, including parks and grocery stores, face demolishment, and were often subject to rent gauging.

When new housing developments for African Americans were proposed outside of redlined areas, or on boundaries, they usually faced steep opposition from city leaders. After WWII, white Americans moved to suburbs like Compton. In 1952, Los Angeles’ courts struck down Compton’s race restrictions, and the racial makeup of West Compton changed dramatically—with Black people and white people living side-by-side well into the ’60s. There was strong opposition to the decision to allow people of all races to purchase homes, but as more and more people of color moved in, bona fide racists left (or went to slower-to-progress East Compton).

Them relies on the history of redlining to tell its story, with 1953 East Compton being the location. Writers likely chose Compton for its being well-known today to have a large African American population—a kind of “Gotchya!” where we know the Emory family’s trials and tribulations were for naught. However, the show’s location is just another over-simplification. Co-creator Little Marvin has readily admitted that Them was inspired by Dr. Emory Hestus Holmes’ experience in Pacoima, Los Angeles and Nat King Cole’s in Los Angeles’ Hancock Park. This isn’t to say the Black experience in East Compton should be ignored, or that it was in any way easier, but Them’s need to force-feed their audience obvious imagery is grating. It wants to hang in the rafters somewhere between horror film and documentary, not minding that it boils down to little more than trauma porn.

Exploiting Trauma for White Audiences

There are a large number of essays that delve into trauma porn (Brandon Taylor’s essay on Them and Black Horror as a genre is a must-read), especially with Them. The show appeals to white audiences, not people of color. The white characters are racist characterizations that make the audience think, “My family wasn’t like that.” It allows the sanctimonious to screech from their rooftops that they would never act like that. The show creates a narrative that racism in the ’50s was always blatant when, in actuality, most racists (both back then and today) relied on a series of microaggressions to get their point across, especially in traditionally liberal areas.

When one looks at the historical record, it’s common to find Northerners who said things like, “I have no issue with the person’s race! It’s my housing value,” rather than people saying, “I hate [insert ethnic group here].” That doesn’t mean acts of violence didn’t occur (see Holmes’ and Cole’s stories above), but it was almost always explained away as protecting an investment. What Them fails to do is to convey the outward appearance and excuses its white residents would have used to justify their racism, instead of creating boogiemen most people can’t relate with.

Finally, the recurrent storylines revolving around infanticide and feticide contribute nothing besides, again, creating mythical white ghouls that make white audience members separate themselves from the storyline and Black audiences turn off the TV. Again, this isn’t to say things like this did not happen, but in the context of the show, it feels separated from the historical record.

Conclusion

Them had the opportunity to create something great, but instead, it became a gigantic mess. The show caters to white audiences and misuses historical facts to create a story that isn’t worth telling. It would have done itself a favor by connecting to real events and factually telling those stories, making its audience members look in the mirror at their own prejudices. Unlike Us and Get Out, Them opts for horror tropes and jump scares while playing around with history to create a disconnected storyline.

I always find it odd when White critics claim art created by Black people was specifically for White audiences. It was a claim laid out to Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and now the creators of “Them,” and I will bet my last dollar that if you asked any of them (pun intended) if their intention was to appease the White gaze and there would be a unanimous, “HELL TO THE NO! NEVER!”

Horrible review. Unfortanately, YOU fail to realise the correlation of the season series and reality.