Have you ever had a word rattle around inside your head? Seemingly out of nowhere, there it is clanging around your cerebrum and the forefront of your tongue. Maybe you don’t even understand the word or where you picked it up, in a movie or a song, perhaps. Or maybe a word has made you so angry it wiped a smile right off your face and left a clenched jaw in its wake, turning your hands to fists. Bruce McDonald’s 2008 film Pontypool is an unconventional zombie film that turns the English language into the virus and radio listeners into a blood-thirsty mob.

I think what’s special about Pontypool is how stripped down it is for a zombie film, especially being released in 2008, amidst the height of the subgenre’s re-emergence. The film wasn’t the usual Hollywood fare of big guns and triggered explosions where survivors raced through the streets of a lifeless city, passing by iconic buildings and locations while being chased by spectacular-sized hordes of the undead. Instead, Pontypool is claustrophobic, encapsulating the viewer in a radio booth beneath a church where the news story coming in from the outside world is one of sheer unbelievability met with caustic doubt.

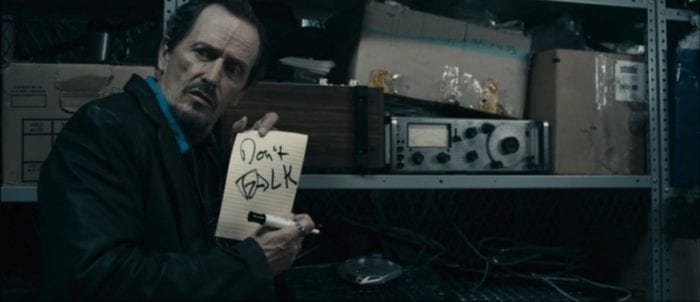

Stephen McHattie stars as Grant Mazzy, a once-celebrated shock jock radio host who now finds himself working for a local station in the titular Ontarian small town. Having been used to the audience offered by a much larger broadcast, Mazzy becomes quickly bored with his new local job located in the aforementioned church basement where the station’s traffic chopper is just sound effects played in a truck while a man at the top of a hill reports what he spies in his binoculars. Mazzy decides to begin preaching his twisted perspectives of the truth rooted in conspiracy theory and paranoia in the hope of riling people up in the process.

If you’ve never seen Pontypool, don’t worry—you’re likely not the only one. The film wasn’t overwhelmingly successful, but I love independent gems. Pontypool is a diamond that I found myself recalling a lot between 2016 and 2021. I find that it’s one of the most cerebral and effective zombie film experiences since George Romero’s The Night of the Living Dead and presented as if it were Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast. What has made this independent Canadian film so easy to consider throughout the last five years is the film’s main concept that words are powerful and have an impact. Pontypool uses a zombie plague that stems from infected words, where, once heard, they drive the listener into a state of madness. Even more captivating than the already interesting premise is that the person everyone is listening to for updates and information regarding the illness, Mazzy, is the one perpetuating the virus.

By now, you may have a good idea where this essay is going, and you’re probably right. I began writing versions of this piece the week that insurrectionists made their way into the Capitol building. I watched as raucous men convinced others to do their bidding in the name of “Making America Great Again,” and it wasn’t hard to see how the country had arrived at this point after a summer of protests and four long years of misinformation, propaganda, and agitation. As I sat and stared at my phone screen, I could only look on as hordes of people made their way to cause chaos inside the Capitol building. The obvious reference was that it looked like a group of motivated zombies. The idea that they were out for blood over the rhetoric that came from one person’s mouth, however, reminded me of Pontypool.

For Pontypool‘s Mazzy, it’s mainly local town gossip he’s spewing, mischievously spreading unsubstantiated rumors about drug dealers creating minefields in their backyards and the drinking habits of local police, feasting on the paranoia of small-town folks for his own amusement. Fighting with his producer, Sydney Briar (Lisa Houle), Mazzy offers his wisdom on creating a loyal following with a “take no prisoners” approach:

I am trying to piss a few people off because that’s how it’s done, simple as that! You see, a pissed-off listener is a wide-awake listener, and he ain’t gonna change the station! In fact, he may just call his pissed-off brother and get him to listen, and then his pissed-off brother may call…I don’t know, his pissed-off preacher, and that Lady Briar is how you build a loyal listening audience!

There’s a lot of truth in Mazzy’s assertions, and it may also have been similarly deduced by the Trump campaign that riling up their supporters and “pissing people off” on both sides was the way to a successful election in 2016. Loyalty was all Trump needed, something James Comey wrote about witnessing firsthand after the 2016 election before comparing the former president to a mob boss. And it isn’t like Trump couldn’t expect that type of complete loyalty from his constituents, especially with how it came so naturally to him to piss off the left, whether it be through policy or just condemning toward their judgment. The latter also instilled his base with resolve to defend him. In March 2016 at a rally in Fayetteville, North Carolina, Trump alluded to paying the legal fees of anyone willing to punch a protester. Of course, if you don’t remember, you can likely guess what happened next. It wasn’t the only time that violence broke out or was even considered an option at one of these rallies, but people are generally suggestable, especially when the idea comes from someone with a platform or a position of power.

Mazzy can propagate rumors and unsubstantiated claims to his listeners so easily because this is who he is. It’s admitted in the quote above, and it’s likely the way he rose to the top in the big city before, but his platform becomes increasingly dangerous as he spreads disease over the airwaves. The longer he speaks, the more people begin turning into flesh-eating monsters—not unlike being told to march down Pennsylvania Avenue and up to the Capitol building and encouraged to “fight like hell. And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.” That message embedded itself into people’s heads, motivating them to take incendiary action, and those actions led to the deaths of four people on January 6 when a similar mob took over the Capitol building.

Maybe it’s the fact that we’re still in the midst of a global pandemic that comparing these events to a zombie film seems blatantly obvious, but the pandemic does play a part in this, mainly as evidence that having a platform can be dangerous. As the death toll rose last year, we all saw those stomach-turning images of mass graves being trenched on Hart Island in New York. Yet our president, having likely the greatest platform on which to be heard, said he probably wouldn’t wear a mask, which encouraged many to do the same. In fact, he actually told people to inject themselves with disinfectant and sunshine—and people considered that. After he boasted about the benefits of hydroxychloroquine, which was later found to have little to no effect on those afflicted with the coronavirus, a man and his wife ingested fish tank cleaner after finding chloroquine among the ingredients.

In Mazzy’s defense, he doesn’t know what’s happening outside his studio, and he has no suspicions that he’s the main cause of it. Sitting in the confines of his self-described dungeon, he refutes the incoming reports of mass chaos coming in, as their traffic reporter, Ken (Rick Roberts), conveys his own disbelief in witnessing hundreds of people running into a building, overfilling it, and causing them to burst out of it. As Ken describes this explosion of people on the air, Mazzy understands that something is happening but cautions himself as a skeptic to the event. Maybe it’s because he’s so used to manipulating other’s thoughts that he begins thinking that someone is pulling a prank on him instead.

The fact that Mazzy broadcasts out of a church may also add credulity to his broadcast within the small town, as well. Is he more believable because he’s broadcasting his version of the truth from the inside of a church? I think that we ingratiate this thought into our political belief systems. The Republican party, being the side aligned with the Catholic Church and Christian beliefs, has made it seem more like the party of righteousness, establishing an indelible quality in them that these are the good guys you can trust. God doesn’t speak for men. Men, however, claim to speak in the name of God. The church, as well as many of these empowered “good guys,” have been through their fair share of controversy. As Martin Luther said, “For where God built a church, there the Devil would also build a chapel,” meaning there will always be those that would take an advantageous angle. This isn’t to say Democratic representatives haven’t had their issues, as well, or even have tried to appeal to the bipartisan middle by exacerbating their religious appeal, but most do not tout their belief system. As a result, “nearly all non-Christian members of [the 117th] Congress are Democrats.”

Now, maybe you’re a right-wing supporter, and perhaps you’re getting mad that this website isn’t just writing about A Nightmare on Elm Street or Friday the 13th. Horror has always found insight into culture and politics and continues to bring us stories such as Pontypool that ask us to recognize problems and move toward change. Regardless, you’re always entitled to your opinion. In fact, that’s the thing that makes this country one of the best to live in and what makes watching what transpired in January so sad and disheartening. Successful coup d’états almost always leave countries in the hands of militarized authoritarian governments that invoke martial law, repressing their people, and leading to the disappearance of those that opposed or criticized the regime change. Argentina in 1976 comes to mind. I guess the question is, what kind of change was expected from this in the United States of America? Kangaroo court cases and public hangings? Is this what we’ve become, a country ready to accept propaganda and wipe out any trace of oppositional thinking?

Mazzy says, “Trauma is a news photo without a caption,” quoting French essayist Roland Barthes to convey his fear in unknown circumstances as they await answers to the bizarre happenings taking place around town. The quote itself brings to mind many images that we’ve seen in the last year. There has been trauma in the Capitol riots, in the Black Lives Matter protests, and throughout the pandemic. The difference now is that the caption keeps changing to appeal to people’s feelings and not to critical thinking. People side with the saccharin spin that appeals to them over the hard, bitter pill of fact-based investigative journalism. Insurrectionists willing to overthrow democracy are only called “protesters” by some media outlets, when, in reality, what they engaged in was treason. If you’re considering an angry response, just google the definition.

Maybe it’s the difference that half of the country can sit in disbelief of the other half as they hang onto every word those like Tucker Carlson or Donald Trump say, which really worries me—those that no longer consider an alternate viewpoint that allows for skepticism unless it’s coming from the party with which they’ve sided. Some convince themselves to get involved in revolutions of political beliefs while rallying around conspiracy-laden news stories to the extent that any intelligent news organization has to be chastised for questioning or criticizing policy. And at the forefront of it all was the country’s leader tweeting out the bulk of it, making both sides angry, but moving the white nationalists within his base to “stand back and stand by.”

The most obvious comparison between the January 6 event and Pontypool occurs when Mazzy boldly walks outside with the assumption that he’s being put on. As someone who’s used to providing the daily dose of local paranoia, he feels like he’s being made the butt of a joke or like his new producers are trying to reign him in by teaching him a lesson. There may be something to be said here about the number of staff that the former president went through during the course of his term, but I’m trying not to go too far down the rabbit hole. Mazzy puts the whole station in danger as the repeating zombies begin pounding on the church doors. Now, imagine those are the virulent voices of insurrectionists repeating the soundbites and tweets of the former president as they force their way into the Capitol building.

Any rhetoric or vitriol Mazzy spews on the air in the name of ratings and attention is put away by Pontypool’s end in an attempt to help the people listening to him. Mazzy proposes hopeful change by turning violent words like “kill” into “kiss” over the airwaves to help the Pontypool listeners affected by the diseased words. Mazzy bets his life on trying to do the right thing before the church ceiling is blown in. It’s the complete opposite of what we’ve seen on social media feeds and in speeches from the former president, who has reveled in hearing his words repeated back to him at his speeches and rallies even when they heartily express racist overtones.

Language is the topic of many films, from A Thousand Words where a fast-talking Eddie Murphy must choose what he says carefully as he only has so many words remaining, to the Oscar-winning Arrival where super linguist Amy Adams is given the gift of time travel by an alien race. The obvious connection between these two very different films is the exploration of how we communicate with one another. Personally, I believe that the planet has a communication problem. There are billions of people on the planet, and it is truly special if even two of them can connect—and that’s without diving into the thousands of languages, dialects, belief systems, etc. that keep a lot of people from ever having a connection. Even people that speak the same language have trouble finding the right words. We are all given the freedom to say whatever we want, but a lot of the time, we don’t bother to listen to anyone before it’s our turn to speak again. It feels like empathy is often in short supply, even though it’s being preached to many on the altar every Sunday.

As I stated earlier, I have made multiple passes at this piece and have often caught myself becoming objectively upset throughout the writing process about the state of affairs that brought this country to that moment on January 6th. The idea is that words still mean something and that we have to understand that people are listening. There are so many powerful hate-filled words, racist words, swear words, and condemning words that people are subjected to daily that it becomes difficult to remember there are a lot of hopeful words too. Pontypool, in its apt and macabre way, tries to focus on how to fight the disease of an anger-inducing vocabulary, so let’s take a page out of its playbook and let’s turn “kill” into “kiss,” try to take back our sanities, and, after a year the entire world is still reeling from, find a way to evolve the conversation beyond the soundbites of a vicious mob.

Mr. Parker,

I just watched this movie for the first time tonight and stumbled across this post. I wonder how you feel about your statements in this piece now with the current state of affairs. I certainly see a similarity between the movie Pontypool and Jan 6th, along with all of the destructive and harmful things that have been said during this last election. My heart hurts for this country, and I fear for the future.

I echo Mr. Ward’s sentiments. Left extremists never seem to miss an opportunity to villianize the former president, even when reviewing a horror film. So, “motivated zombies” rioted at the White House on 1/6, but all of the BLM, Antifa, and cancel culture inspired riots – a whole summer of destruction, demoralization, and death – none of those folks were wide-eyed crazed extremists tearing at the fabric of society? Of course not; those identifying as “oppressed” or “marginalized” got a free pass to wreck havoc across America for months, all accepted with open arms by the left. I’ll suggest a few dangerously viral words for you: equity … inclusion… microagression … transgender … critical race theory. Buzz words designed to trigger SJWs into a state of mindlessness, driven to seek out and destroy the “aggressors.” I guess the definition of “zombie” depends quite a lot on what side of the political fence you sit on for purposes of reviewing this article.

I love how the writer of this review references the Capitol protest as being synonymous with this movie. Absolutely no similarity whatsoever and just goes to show how misinformed people are who just want to hop aboard the “anti-Trump” bandwagon because it’s “what everybody else is doing”, without having any substantial or credible knowledge whatsoever.

Notice how you never named a specific thing that was “misinformed”? Notice how you just assume people’s intentions without backing it up. You are literally doing exactly what the film is saying NOT to do. You are using buzzwords to paint the writer as something he is not. The writer outlined in detail in this long ass essay the similarities between the Jan 6 insurrection and this film and you can only pathetically cough up a few measly bitter sentences with no evidence of any kind? Talk about a lack of substance. You’re so unaware of yourself, it’s actually pretty sad.

Amen. I stopped reading once the political nonsense started.

People who showed up at the capital were largely gullible and easily manipulated. The same is true For those who believe the attempted coup was just a a “protest.”