In a previous article discussing the horror cinema of the 1960s, I referred to Psycho and Night of the Living Dead as the two most important horror films of the decade, as well as the two films most instrumental in the shift from classic to modern cinematic horror. I wanted to explore—over the course of a couple of weeks—each of these films in a bit more depth than the survey format of that article allowed for. Last week, I discussed Psycho, this week: Night of the Living Dead.

*Author’s Note: For those of you that read my piece on Psycho last week (and, I mean, why wouldn’t you have read it?), you may recall that in it I alluded to the use of Bosco chocolate syrup to create the blood in the film’s famous shower scene. Well, in doing some cursory research on Bosco, I discovered that the very same syrup was used for the very same purpose in the very film I am about to discuss (very interesting, no?). Anyway, for that reason, I am officially unofficially bestowing on these two articles, collectively, the title “Bound by Bosco: Psycho and Night of the Living Dead.”

If you find that even slightly amusing, then may you enjoy the following piece at least as much as you enjoyed that bit of jocularity; if you did not find that even slightly amusing, then I encourage you to continue reading nevertheless, and may you enjoy the piece that follows far more than that bit of nonsense.

Connective Tissue

Just as 1960 and 1968 are drastically different years (indeed, they feel as if they are separated by more than a mere eight years), so too are Psycho and Night of the Living Dead radically different films—or at least seem to be. Their superficial differences in fact belie their more significant and clear connections. Certainly, where Psycho is arguably as much a mystery-psychological crime thriller as it is a horror film, Night of the Living Dead indisputably belongs to the horror genre. Furthermore, in nearly every regard where Psycho showed at least some restraint, Night of the Living Dead does not.

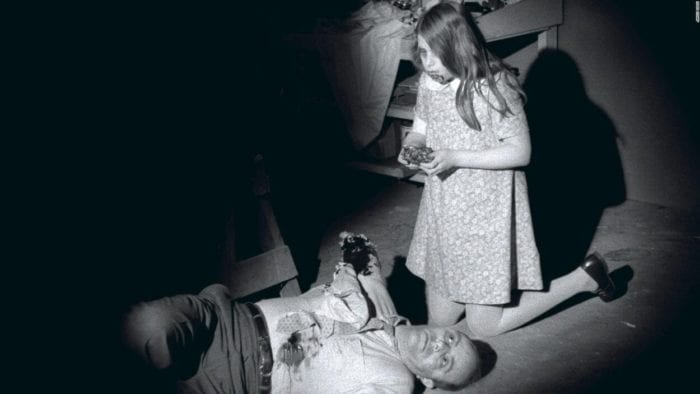

However, it’s important to note that Night of the Living Dead is not without its own moments of suggestive horror, e.g. Mrs. Cooper’s death at the hands of her undead daughter is depicted in a manner not unlike the shower scene in Psycho, in which we never actually see the blade puncturing flesh. Nevertheless, Night of the Living Dead is certainly the more graphic of the two films. Surely, this is partly due to changes in what was permissible in 1968 as opposed to 1960, as well as the fact that Psycho was a major studio film, while Night of the Living Dead was an independent production. These differences notwithstanding, both Psycho and Night of the Living Dead are, in their own ways, quite visual in their depictions of onscreen horror.

While the shower scene in Psycho is noted for its meticulous use of camera angles and editing to present the murder as impressionistically as possible, it is nevertheless a rather bold display of violence, especially for 1960. Similarly, while the shots of the undead feasting on human organs in Night of the Living Dead may seem fairly tame today, for 1968 they were quite shocking.

These unflinching and bracing depictions of violence are, of course, the most overt link between the two films. However, in both films the murder and mayhem are also greatly amplified by other contextual elements; it is not merely that the events themselves are horrific and the visuals shocking. For example, in Psycho, everything from who the target of the violence is to when it happens to what happens after the murder adds to its impact; similarly, in Night of the Living Dead, it is significant that the remains the ghouls feast on are those of the young couple after their ill-fated escape attempt ends in a fiery death. The film actually piles on a little additional revulsion later on during a relatively calm moment, when the worst of the horror is ostensibly over, when one of the roving militiamen, coming upon the sight of the burned wreckage, callously remarks that someone must have had a barbecue.

Thus, each film goes a step further than merely depicting the moment of violent death itself by also showing its aftermath. In these films, we see the reduction of the human body to a useless thing to be disposed of, as well as the methodical and matter-of-fact clean-up of the murder scene (itself a further erasure of the victim’s existence). Additionally, we feel the accompanying death of hope and the overarching sense of cosmic indifference. In making what was once implicit now explicit by showing—even lingering—on the grim realities of death, Psycho and Night of the Living Dead share a certain thematic and aesthetic consistency despite their outward dissimilarities.

In addition to their shocking depictions of violence and its aftermath, other shared elements link the two films. Both make great use of their mundane settings, juxtaposing them with their narratives’ horrific events and, at the same time, using that mundanity to further ground those events in reality, which in turn heightens their impact. In both films, there is a breakdown or perversion of normal social relations, particularly of familial relations, resulting in violence and dissolution. The violation of taboos against the desecration and defilement of the body (both living and dead) features heavily in each film, with Night of the Living Dead adding cannibalism to the mix and Psycho even hinting (albeit very obliquely) at incest and necrophilia (the former representing perhaps the ultimate perversion of the familial bond). These elements together lend these films a bleakness of effect to match their stark visual styles.

Love Is Dead. And We Have Killed It.

Issues of oversimplifying and romanticizing aside, the summer of 1967 is popularly known as “The Summer of Love”. Misnomer or not, the term made some sense, as it was at this time that the Flower Power/Free Love subculture truly took shape in the popular consciousness and gained the status of something approaching a “movement”. However, just one year later, even the thought of applying some similarly happy moniker would seem utterly cruel and perverse. Besides direct US involvement in Vietnam reaching its apex in 1968, within a span of two months between April and June, both MLK and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated.

Though these specific events transpired after production on Night of the Living Dead had already wrapped, and thus were not a direct inspiration on the film, they loomed large over the film’s release, real-life horrors providing an inescapable context for the film’s onscreen atrocities. Just in case anyone wasn’t quite sure, Night of the Living Dead was a cinematic confirmation of the fact that, to paraphrase Blue Oyster Cult eight years later, this was not the Summer of Love.

This ain’t the garden of Eden

There ain’t no angels above

And things ain’t like what they used to be

And this ain’t the summer of love-“This Ain’t the Summer of Love” (1976), Blue Oyster Cult

Night of the Living Dead is a film in which love, both familial and romantic, does not win out in the end. In 1968 and even within the horror genre, the redemptive power of love (typically between people, but love for one’s community/nation/humanity could fit the bill) was still commonplace enough to be considered a trope. There had, of course, been exceptions to the rule prior to Night of the Living Dead (especially within the horror genre), but Night of the Living Dead is a film that does not merely eschew the convention but seems to actively attack and subvert it.

Consider how love fares in the film: the young couple dies horribly and their remains are feasted on by ghouls; Barbara is eventually dragged off by her now undead brother (who earlier failed to protect her from the film’s initial ghoul attack); the older, married couple, the Coopers, bicker constantly, and the Coopers’ infected daughter (meaning they too failed to protect a loved one) partially eats her father’s corpse and then stabs her mother to death. Family (siblings, parents, and children), marriage, young love—all are mowed down in the course of the film’s increasingly unfortunate series of events, a case of a grim forward momentum that feels distinctly like implacable and indifferent fate.

The Fault Is in Our Stars and Ourselves

As each character meets their demise, the mounting sense of inevitable, impending doom grows, even as each death remains shocking and tragic, and none more so than Ben’s. It may be more accurate, then, to say that, upon initial viewing, each death—especially Ben’s—is upsetting precisely because it is unexpected; upon subsequent viewings, those deaths remain equally unsettling for the fact that they have now come to feel nearly preordained. It is thus particularly upon subsequent viewings when the awful inevitability of the film’s events begins to take shape, that its very title comes to have a kind of double meaning. While Night of the Living Dead clearly refers to the film’s cannibalistic ghouls, so too can it apply just as easily to the film’s human characters, all of whom will be dead by the end of the film. I don’t believe this was intentional, but it nevertheless dovetails nicely with the film’s unremitting nihilism.

On that note, it bears repeating that it is the film’s final death that hits us the hardest. When Ben is shot, it completes the film’s cycle of death by killing off the last remaining major character (and our hero, no less). While Ben is no doubt the hero of the film, it is interesting to note that some of his most fateful decisions actually turn out to be wrong. For one, it is his plan to fuel up the pickup truck in order to escape that goes terribly awry and results in the horrific death of the young couple. Additionally, while he was adamant throughout the film about staying upstairs rather than going down to the basement, he ultimately survives the ghouls only by finally retreating to the basement. Thus, not only was he wrong, but Harry (the film’s highly unlikeable human antagonist who, among other things, at one point cravenly leaves Ben to die at the hands of the ghouls) was right.

Of course, neither of these are mistakes Ben can reasonably be faulted for; nor do they make him less heroic. He is still, by far, the most resourceful and admirable character in the film. What it does mean, though, is that he is an imperfect hero (as real heroes are). In this film, as in life, sometimes good people can be wrong and, conversely, occasionally bad people (or at least people we don’t like very much) may be right. It’s a great example of a subtle way in which the film imbues an inherently fantastical scenario with a bit of realism and complicates the typically two-dimensional Hollywood depiction of hero vs villain.

With the death of Ben, the audience is left with no surrogate through whom we can feel that familiar and comforting sense of “We made it.” Up to this point, the vast majority of horror films afforded audiences at least some measure of relief and some glimpse of hope (many do even now). At the end of Night of the Living Dead, we are left only with characters to whom we have just recently been introduced, about whom we know nothing, and whose only meaningful action has been to kill our hero. We cannot, nor would we want to, relate to these characters; nor do we share in any sense of camaraderie or victory with them.

By killing off the last character with whom we could identify (the character we have, in fact, been identifying with) the film essentially tells us “No one survives,” a harsh truth we feel every bit as much as we understand intellectually. Furthermore, the fact that Ben is killed not by the ghouls, but by a member of an armed vigilante mob, only makes his death more tragic. The irony of his surviving the titular night of the living dead, only to be killed by the living (the ostensible “good guys”), is bitter indeed. The fact that his death appears to be an accident, a case of mistaken identity, does little if anything to soften the blow.

Additionally, the impact of his already tragic and senseless death is only exacerbated by the optics (captured in grainy, B&W still shots) of a black man gunned down by white men who subsequently throw his body on a makeshift funeral pyre. In fact, in a bit of nasty irony, the entire portion of the film after night has given way to day, with its scenes of roving militias traipsing the landscape, “neutralizing” the ghouls as helicopters fly low overhead, is when the film’s visuals most explicitly evoke the real-life horrors of racist, vigilante justice, as well as the death and destruction wrought by US involvement in Vietnam.

We’re Not #1?

As noted in my previous article on the horror films of the 1960s, it is fitting that the decade essentially began and ended, respectively, with these two films. Psycho, with the slash of a knife and the artful use of chocolate syrup, declared that what had passed for cinematic horror to that point would no longer cut the mustard. From Psycho on, the genre would be forced to reckon with the fact that we (well, other people anyway, certainly not us) are the most frightening monsters of all, precisely because we are the only monsters that are real.

As the decade began to wind down, Night of the Living Dead, with its gritty and raw style, its refusal to provide any sense of hope, and its general unpleasantness, only further cemented the fact that the old school frights of horror’s past had lost their potency; from this point on, it would take a great deal more than the tried and true clichés of yesteryear to shock audience’s sensibilities. Tellingly, though, even with the visceral horror of the undead killing and feasting on the living in graphic fashion, perhaps the most disquieting aspect of Night of the Living Dead was (and is now) its message that even in a world turned upside-down by marauding undead ghouls, it is still the inhumanity, ignorance, and selfishness of the living—our fellow human beings—that poses the greatest existential threat.