This article is dedicated to the loving memory of my best friend, Dean J. Griffiths, who played a Transylvanian in “The Rocky Horror Show” and would always film, cheer me on, and dance along whenever I’d sing Rocky Horror songs at karaoke. I miss you more than Riff Raff and Magenta miss Transsexual, Transylvania!

“Horror-comedy/musical” is a whole category unto itself. Three genres so frequently misunderstood, dismissed, or otherwise minimized, can create such magic when they’re put together. Take it from someone who played Elizabeth in the Young Frankenstein musical: there’s something very special that happens when these specific genres are strapped to the slab and electrified.

Some people are surprised to find out how much I enjoy The Rocky Horror Picture Show (even writing about it myself previously), but for anyone who knows me, it’s certainly no secret. (Absolutely no secret.)

When setting up this series on analyzing horror-comedies and how each movie uses and blends those elements, this 1975 cult classic film that flaunts its weirdness was a natural fit. Even years later, the film remains unique.

“You’ve arrived on a rather special night,” because, without any further ado, it’s time to come in out of the rain, dry off with a mysteriously bloody rag, and dance right into how The Rocky Horror Picture Show experiments with horror and comedy to make a film strong enough to endure through generations. Are you ready?

The Comedy

The comedy, to put it frankly (no pun intended), comes from two sources: just how insane and “out there” pretty much everything in The Rocky Horror Picture Show is, and how seriously the characters take the whole situation. From the characters to the songs, to the dances, to the costumes, and to all the twists and turns of the plot, unsuspecting viewers get dunked into the deep end of The Rocky Horror Picture Show in the same way Brad Majors (Barry Bostwick) and his fiancée, Janet Weiss (Susan Sarandon), are dunked into the deep end (eventually, literally) of Dr. Frank N. Furter’s (Tim Curry) world he’s carefully constructed—in more ways than one—for himself.

While the big turning point into just what this film is going to be is certainly the introduction of Dr. Frank N. Furter, we do get enough glimpses of it beforehand to get us acquainted with aspects of the movie that’s coming. These peeks into the film’s world get the audience used to laughing at the absurdity, rather than fearing it.

Long before the fateful thunderstorm, a disembodied pair of lips delivers the first song. It’s strange, but the lyrics are clever and the lips exaggeratedly expressive, and so, rather than being creepy, it’s comedic.

Brad and Janet, our “heroes,” play the part of “innocent about to be swept into a twisted world,” and are presented as so cheesy, so square, and so straight-laced that, while we do wish them well, we also laugh at them, as well as their exaggerated reactions to everything. When Brad and Janet are afraid, we’re laughing.

Introducing Brad and Janet via musical number also solidifies the film as a musical; not only that, but a lighthearted musical. So by the time the Transylvanians are pelvic-thrusting around, it’s not the fact that there’s a musical number that catches the audience off guard, but the flagrant disregard of norms surrounding gender and sexuality.

But…if the movie’s already busy being a musical comedy rebelling against restrictions on gender roles and sexuality, where does the “horror” part of The Rocky Horror Picture Show fit in?

The Horror

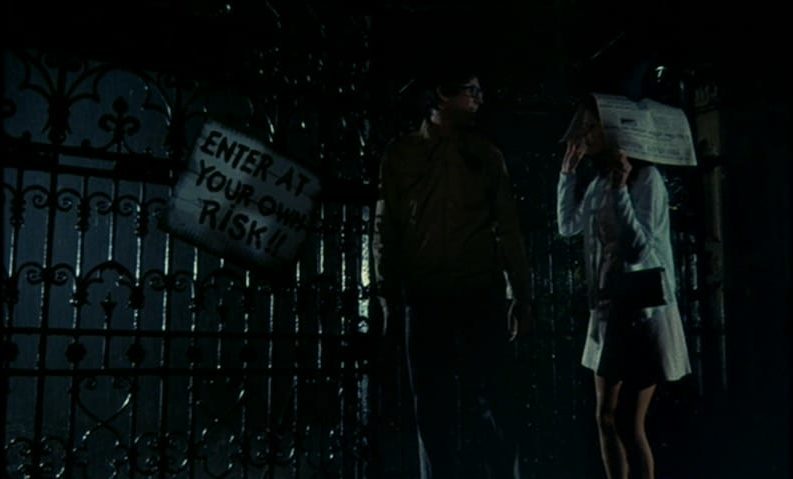

The “horror” part of The Rocky Horror Picture Show comes from the basic framework and tropes of horror movies that the film takes. Innocent people getting stranded and going to a mysterious castle for help; a hunchbacked assistant (Riff Raff, played by Richard O’Brien, who also wrote the original musical); a mad, eccentric scientist; a science experiment straight out of any version of the Frankenstein story, but most specifically, Hammer Studios’ The Curse of Frankenstein (note Dr. Frank N. Furter’s use of a vat instead of a metal lab table with straps); and of course, the traditional “ignoring of the warnings.”

With The Rocky Horror Picture Show remembered for being fun, free, and rebellious, it can be easy to forget that Dr. Frank N. Furter commits a grisly murder, serves that murder victim for dinner (in the middle of the night, for some reason) to unsuspecting guests…including the victim’s uncle, creates life with the sole goal of making that person a sex toy, has apparently used and abused many before Rocky, takes advantage of Brad and Janet during the night through deception, and more. On paper, Dr. Frank N. Furter has a rap sheet as extensive and depraved as some of the most feared horror movie villains.

So…why are audiences (especially 1970s audiences or modern, but unsuspecting audiences) smiling, amazed, and even rooting for the “villain,” rather than repulsed?

How They Mix

The characters in The Rocky Horror Picture Show take the various goings-on very seriously—a little too seriously. Sure, watching a party full of people suddenly break out into an organized dance number may be surprising (at least, if you’ve never seen people do the Electric Slide, the Cha-Cha Slide, or the YMCA), but witnessing such a scene, especially with a dance as tame as “The Time Warp” (give or take a “pelvic thrust”), probably wouldn’t make the average person scared to the point of making a hasty retreat.

The film takes the aforementioned horror framework and tropes and twists them into “wacky” territory. The hunchbacked assistant is also a rock-and-roll singer who starts a lively dance number. The mad, eccentric scientist dances all around the lines of gender and sexuality until you can’t even see them anymore. The result of the mad, eccentric scientist’s experiment isn’t the sewn-together, deformed, murderous monstrosity that even non-horror fans would expect: instead, he’s a muscular man in shiny gold underwear who, despite his strength, doesn’t have the capacity to hurt anyone. Yes, the Frankenstein monster didn’t always intend to murder people, but Rocky (Peter Hinwood; Trevor White, singing) seems more interested in lifting weights.

The Criminologist (Charles Gray) is another fitting example of this. His performance is gravely serious: coldly, analytically presenting the facts of a serious case to which he has no direct connection. His flowery descriptions and metaphors, while dark and foreboding, go so far that they swing the (heavy, black) pendulum back to ridiculous. And it’s very hard to take someone seriously when they’re barking instructions to an energetic and hilarious dance from the top of their desk as they do the dance themselves.

The relentlessly energetic musical numbers add their own spice to the horror-comedy mix: it’s difficult to be scared when you’re tapping your toes. No emotional ballads or creepy tunes here: it’s all fast-paced, dance-worthy music, with the only exceptions being “Science Fiction/Double Feature” and “Super Heroes.” In the case of the former, the lyrics are comedic enough to give the film energy from the start. In the case of the latter, the entire movie that came before it and the explosive finale happening around it keep the energy from dying.

Even “Dammit Janet,” as saccharine as it is and completely void of the rock-and-roll and sexual charge of later songs, is energetic. It also has hints of darkness, with the deadpan (no pun intended) staff (who, upon closer inspection, are actually familiar faces) casually switching the church from a set for a wedding to a set for a funeral, even rotating flower arrangements to show black flowers instead of white and bringing out a coffin. The absurdity of what should be a somber occasion being relegated to casual background noise to a lovey-dovey musical number, with Brad and Janet blissfully and comically unaware of what’s going on with their extremely bored background singers, further trains the audience to see any dark or sadistic happenings as comical diversions, rather than horrific inspiration for nightmares.

Speaking of dying, another sequence that captures The Rocky Horror Picture Show’s tone and style is the entire sequence with Eddie (Meat Loaf). Here’s a character that literally comes out of the wall, but is more concentrated on riding his motorcycle around the laboratory than the fact that he just came out of a “deep freeze” and has a gnarly scar on his head. Even though we have absolutely no idea who this character is or how he’s relevant at all, he’s endearing because of the absurdity of his entrance, the energy of his song, and the fact that Columbia and most of the other characters either already love him or are being charmed by him. We’re not thrilled by any means to witness his murder, but when the murder happens on the tail end of a musical number in the middle of a film in which we’re already laughing at everything weird, wacky, and warped (pun intended), it doesn’t feel like a tragedy.

And really, that’s the answer: the comedy, the satire of gender and sexuality, and the fun come first in The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The horror is a frame: the outlines in a coloring book. But it’s the colors that give the film its character. They’re different from the colors that are “supposed” to be there, they come from lipstick and eyeliner instead of crayons, they zigzag around the lines, they draw new lines and then zigzag around those, and you’re left with a colorful work of art that the initial lines, whether of horror tropes, gender expression, or sexual expression, could never dream, much less be.

Dean, although I loved everything “Rocky Horror” long before we met, it’ll always make me think of you! A toast…(throws toast)…to absent friends.

Very well-written article. The Rocky Horror Picture Show is a film I’ve watched countless times but I think I’ll watch it again with some new insights after reading this.