When a horror film reaches new heights, we often reach for the same familiar words like awesome, brutal, and sick. We use these words with such frequency that they lose their meaning. They become amorphous synonyms for the same, elevated sense of really, really, good. We don’t mean a film was so bold, arresting, and uncompromising that it leaves us in the same awe that might exist in the presence of a dark god. We don’t mean a film that threatens us with the harm of its viewing. We certainly don’t films that make us truly sick. Unless we’re talking about Takashi Miike.

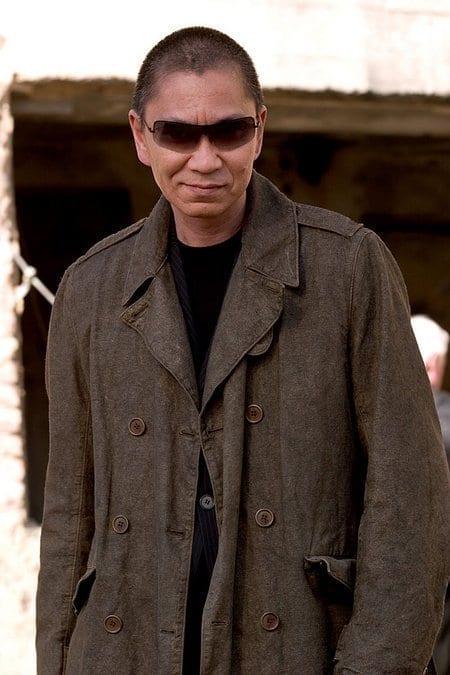

With over a hundred directing credits, Takashi Miike earns his Icon status with his work ethic alone. Luckily, he also has the unique artistic flair, sense of vision, and disrespect for the rules that alloy together into the metal that icons are forged from. While his journeyman career has created children’s films and crime dramas, he’s known first and foremost for his elevated and caustic horror films. Miike’s work employs these talents to craft stories about tension, the human capacity for evil, and the many dark, crawling things that wriggle underneath the world we know. His every entry into the horror canon seems finely crafted, an intricate nest of clockwork ticking towards the ultimate goal of making his audiences gasp, bite their nails, and vomit.

I don’t bring up the latter without receipts. In the 15 years, I’ve been a horror fan, I’ve never had a movie make me physically sick enough to throw up until I saw Audition (1999) for the first time. There’s proof of that film’s visceral power soaking into the spoiled soil of some Atlanta landfill to this day. For the purposes of this review, let’s focus on three of Miike’s best known and most unsettling films: Audition, Visitor Q, and Ichi the Killer and how they relate to the aesthetic principle of abjection.

Miike and the Body

Abjection is the shorthand for experiences that threaten our sense of order, cleanliness, and safety. Abjection in art feels dangerous, disgusting, and transgressive. Miike makes films that feel like we shouldn’t be watching them, turning us into, at best, witnesses and at worst accomplices to his heinous crimes against polite cinematic society. His is a cinema, not of the heart, mind or eyes. Miike reaches through us and grabs his captive audience by the stomach.

There were whispers and shadows of this cinematic raison d’etre in his early works, but they crystallized into a fully realized nightmare in the taut, unbearable, captivating Audition. Adapted from Japanese literature’s enfant terrible Ryu Murakami, Audition follows an aging widower, Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi), and his pursuit of a new wife. His friend from his filmmaking days proposes that they hold a fake audition to find the perfect candidate. What he finds instead is the quiet, angelic Asami (Eihi Shiina), but Asami has a tragic past and a secret that will plunge both characters into hell. Miike uses this simple Fatal Attraction (1987) premise to weave together a David Lynchian nightmare-scape of sordid characters, torture, and bodily fluids. By now, to fans of the genre, the last 20 minutes of Audition are infamous for their inventive torture involving cheese wire, needles, and girlish laughter.

Miike’s choices are specific with all of the violence in Audition, focusing on injuries we can relate to. When someone’s head is chopped off in a horror movie, it becomes a gratuitous spectacle. It can be nightmarish, but it’s not abject. We don’t feel it. When Asami digs long acupuncture needles into Aoyama’s eyes, our eyes start to itch. When she cuts into his ankles, we remember when we sprained our ankles on the stairs. Miike brings the pain into our understanding and reminds us that we, too, are fragile and exposed. When, in the scene that brought out the aforementioned vomit, she force-feeds her own vomit to a mutilated man she keeps in a bag, we taste our own bile and look away.

It may seem unsavory, but it’s never gratuitous. Horror movies are often accused of desensitizing its audiences to violence, and that becomes difficult to defend against when faced with another Friday the 13th or Hatchet film that showers us in blood and gives us music to dance to as if we’re all vampires raving in a Blade-esque nightclub. Miike uses his audience to stitch us to his characters. We understand his characters and their choices, the extremes of their behavior. We feel their pain and understand the weight of it. It hurts because they do.

The Sins of Our Cinema

This unpleasant kinship continues in the staggeringly transgressive and bizarre Visitor Q (2001). Often cataloged as a black comedy, Visitor Q connects to a legacy of unsettling portraits of family life like Todd Solondz’s Happiness (1998) or Ari Aster’s notorious short film The Strange Thing About the Johnsons (2011) by way of a Richard Linklater style rambling narrative. While Audition tests its audience’s temerity and tolerance for physical trauma, Q focuses instead on emotional pain by placing its audience at the dinner table of a crumbling family dynamic.

The mother struggles with heroin addiction, the father is cruel, the son faces violence from bullies, the daughter is involved in risky behaviors, and the main character, The Visitor, observes everything with a neutral perspective, reflecting the desires and interests of both the director, Miike, and the viewers. The film relies on digital video, creating a cheap, urgent atmosphere of complicity similar to Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986) that makes the proceeding realist carnival of sex, abuse, drugs, and breastfeeding disturbingly intimate. The blood, and colostrum are on our heads just for watching.

Visitor Q is a film best watched once. That way, you can spend the rest of your life trying to scrub it from your mind while poking and prodding your memories of it for deeper meaning. It perfectly encapsulates the experience of abject art by presenting us with revolting people and deeds, but bid us look closer, like a filthy mirror, until we see ourselves.

Vision of Violence

Miike also understands the extremity of human behavior and how it can shift our world. While he settles for raw depiction of these extremes in Audition and Visitor Q, he places us firmly within the visions of violence itself with his shocking and visionary horror noir Ichi the Killer. Adapted from a manga with the same title, Ichi narrates the tale of the main character, Ichi, a troubled young man entangled in the violent world of the Japanese Yakuza, and a brutal gang war among different Yakuza factions, all while evading the grasp of the fearsome and ruthless mob enforcer, Asano.

Ichi the Killer stands out amongst Miike’s horror oeuvre for its stylistic flourishes. With fast and flashy camera work and heightened color treatment, we feel as though we are no longer witness or accomplices to the violence on screen. We have passed a threshold and have entered the minds of the killers and criminals themselves. The Pulp Fiction-esque twists and turns of the Yakuza become perfect fodder for Miike’s relentless exploitation machine that tells its audience that, to the violent, all violence is spectacle. For killers like Ichi and Asano, the violence is the movie and just as entertaining.

It’s a departure from the stark aggression of his earlier work but hints at a director uninterested in staying the same. He wants to tell a different kind of story from the tense quiet of Audition and the voyeuristic disgust of Visitor Q. With Ichi the Killer, the story becomes about the way violence makes all the world seem violent, and how its inhabitants have no choice once they are first exposed to it. The film begins with a flashback and the brutal sexual assault of a prostitute, with a younger Ichi watching outside the window.

Perhaps that younger Ichi is the old Miike, no longer content to watch and be entertained with the objective reality of somebody else’s violence.

When Ichi enters the room to do his own kind of damage, that is a new Miike stepping into his craft to tell us a bold and dangerous new kind of story about our role as spectators ourselves. Ichi’s murder of that prostitute, his entrance into that world of violence, is a tongue-in-cheek challenge to Miike’s fans. How long will you wait on the window? How long before you make your own spectacle? Between in here and out there, was there ever truly a difference?

Miike is unafraid to ask these questions and torture us until he gets his answers. This courage, this brutal understanding of the nature of violence and art, makes him a horror icon deserving of his place in the pantheon of horror cinema.