Mandy is a revenge film with no pretension. A violent wrong against a couple in love must be righted, and it is done so with equal or heightened violence and intent. When I initially saw it, I left feeling that it seemed to work like The Crow without its heart, while it did manage to remain a highly stylized revenge film by the book, or was that like a book? I needed to sort it, and I’m glad that I’ve spent that time now. Of course, it is different from The Crow in almost every way beyond the rock and roll-influenced revenge film. If The Crow was 90’s Gothic, Mandy is a play on black metal aesthetics sans the face paint, though it would rather you get into an airbrushed van and drop acid to the progressive landscape of King Crimson’s “Starless.” There is no resurrection in this film, and rather than accomplishing blatant justice against evil, Mandy is sneaky in what it conveys. From the Q&A that followed the advanced screening and can be found here, we also know that Panos Cosmatos’s motivations for this film were purely from an artist’s intention as opposed to James O’Barr’s coping with a tragic experience, so far as we know. I cannot call Mandy as pure a love story as The Crow, but the latter does come from a graphic novel, which allows me a connection I would like to propose in the notion of “off the printed page.”

Horror & Heavy Metal Aesthetics

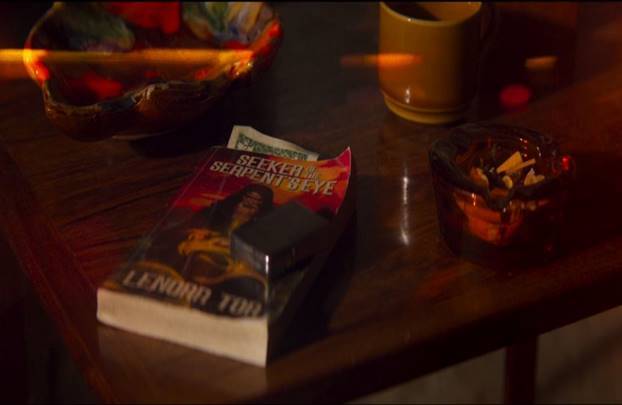

Mandy will take its place in a kind of pulp genre for film, while that by no means infers it is easy to discard. I find myself relating this to the recently published Paperbacks from Hell by Grady Hendrix. The stylization of its chapter headings certainly fits. The character of Mandy (Riseborough) is a reader. Early in the film she tells Red (Cage) that she has been reading about the galaxy, but the nineteen-seventies to eighties-esque, beat-up mass market she is engrossed in is the meta-fictional Seeker of the Serpent’s Eye by the also fictitious author Lenora Tor. Perhaps the author’s last name is meant to point us to Tor Publishing paperbacks. A quick Google search for “Tor paperbacks” sends up a link directly to Paperbacks from Hell author Grady Hendrix’s post from 2015. One of the titles from Jóhann Jóhannsson’s original soundtrack for the film is indeed Seeker of the Serpent’s Eye. The chapter headings I mentioned above punctuate the film into three chapters or books: “The Shadow Mountains,” “Children of the New Dawn,” and “Mandy.” Post-credits tells us that Mandy’s paperback design was by Dan-ah Kim, and the cover art was by artist Viktor Titov, a freelance illustrator who is known for his work for Riot Games. Additional logo designs were created by Jeff Ladouceur. The film even opens like a book with an epilogue: “When I die, bury me deep. Lay two speakers at my feet. Wrap some headphones around my head, and rock and roll me when I’m dead.” There is nothing subtle about it; throughout the narrative of Mandy, we are treading through a beat-up, throwaway fiction every bit as much as we are watching an homage to Heavy Metal comics, the aesthetics of Metalocalypse and Frank Frazetta, the enlivened animation of airbrush paintings off the sides of vans from the 1970’s and 80’s with equal stylization, and, as we will see, a pointed critique on cult leaders and the male ego. We have a lot to talk about.

Love Letters & Satanic Panic

Revisiting the presence of love in the film, its largest projection is in Cage’s anguished facial reactions as he is bound up. It can be confused with the physical pain of his hands and mouth being bound in barbed wire, but this is where we see his true dedication toward the character of Mandy and in the loving, anguished role of Red. There is the refreshing casualness of Red’s and Mandy’s conversational relationship, and whereas Eric and Shelly’s flashbacks in The Crow function as a Gothic valentine of new love, Red and Mandy are well into a settled, adult relationship. That may throw some audiences of the film who feel like they never see the intensity of “true love” on the screen necessary to feel empathy for the characters’ predicaments, leaving them just to fear for their pain and mortality. Maybe the question becomes is this film a love letter? If it is, it is a love letter to the so-called Satanic Panic of the 1980’s and 90’s and the best elements of the phenomenon that were reacted against and misconstrued. Isn’t it interesting that we have seen evidenced in recent pop culture a nostalgia for the horror aesthetics of this time? The credits and title font for Netflix’s Stranger Things, while much tamer than they appear here, reference the era, its forbidden world of Dungeons and Dragons role playing and video game Dragon’s Lair. With some misguided but choice curation in its references (Joy Division and Evil Dead promotional materials in small town America, especially in the 80’s; trust me, the popularity came after the fact, hence the cult status), the show does a fine job in situating what youths’ popular culture looked like in what I’m calling the Satanic Panic era. Mandy concentrates on the adult geek offerings of that culture—Heavy Metal Magazine, horror novels, and Motley Crue.

Cult Leaders, Ego, & Emasculation

At the same time, Mandy portrays a fragile, empty cult with all of the era’s trappings. If the trailer promised Hellraiser, teasing the Children of the Dawn’s amped up henchmen and their subsequent abduction of Red and Mandy (I thought about Cenobites, for sure), what it gave us from Barker instead was Lord of Illusions—the film, not the short story it was inspired by. I would have to suggest that one of the film’s in-references was indeed Jeremiah Sand’s cult brother, Brother Swan, reminding us of the character of Philip Swann, protégé of cult leader Nix. Regardless, we can pull away from the The Crow as an access point to revenge films and turn to cult leaders Jonah King in Drive Angry, Nix in Clive Barker’s Lord of Illusions, and let’s stick with Christopher Lee’s Lord Summerisle in 1973’s The Wicker Man. Who are these cult leaders, or rather, who is Jeremiah Sand in relation to some of these portrayed cult leaders?

In Drive Angry, also starring a vengeful Nicholas Cage as Milton, the occult leader is Jonah King, an assured and capable man of devastating results. He is confident and has surrounded himself with powerful allies. We discover that in a brutal, forced act upon Milton’s daughter, she retaliates by causing him a severe injury, leading to her demise and fueling his anger and resolve to unleash Satan’s vengeance upon this world. He is separated of his manhood but no less determined to lead his people in an apocalyptic ending. Milton’s daughter was as expendable to King as Mandy is to Sand. The cult leaders would have murdered and continued their agendas regardless, even if they could convince themselves otherwise for a moment. In an instance of another seemly castrated leader, we have Clive Barker’s Nix. As the person behind the avatar Valorum opines, “Like most cult leaders (e.g. those without magical powers) he’s become obsessed with his own publicity and has started to buy into his own lies about being able to create an apocalypse merely by thinking about it.”[1] Valorum adds a quotation from Clive Barker on his intentions with the character.

One of the things I wanted to do with Nix was to make him very uncharismatic. There is nothing appealing about this man and, towards the end of the movie, when the temptation would be to go into apocalyptic mode, the movie pulls in exactly the opposite direction. Nix becomes this frail, rather pathetic creature. In one of the final scenes, Dorothea asks the metaphysical question, “What are you?” and Nix says, “I’m a man who wanted to be a god and changed his mind.” And I like that. I like the fact that he is just a man. He wanted to be something more but he gave up on this useless endeavour. He’s murdered all his acolytes, his devotees, and now he’s alone in the dark. I actively went after that, even though it was flying in the face of what the audience expects.[2]

Lastly, we have Lord Summerisle, who lords over his islanders with his knowledge and pedigree. As Antony Trepniak states on the Necronomania site, “Given that he is no ignorant villager and knows the real, scientific explanation of why apples grow on the island, is he to be trusted on this point? Clearly the religion (in which he personally plays a key part) plays a huge ideological role in cementing the absolute control he seems to exert over the island’s inhabitants.”[3] They have no recourse in denying him or questioning the indoctrination. Surely his ego can be sorted out against actor Linus Roache’s statement on cult leaders and ego in his Q&A, linked above.

Jeremiah Sand is undermined three times in this film. Shall we say betrayed? First, he is emasculated by Mandy’s laughter as he prostrates himself gloriously naked before her and his followers. She sees through him and all of his cult’s poisonous intoxicants. Second, when Caruthers explains the plot in glossary fashion to a seething Red, fresh from the loss of Mandy, the cult who seemingly held ascendancy as its purpose is reduced to mere street-thuggery and acid dealing. Third, at the peak of Red’s confrontation with him, he falls to desperately begging for his life with the offer of a degrading act, despite previously convincing the audience of his intense desire for a woman like Mandy. He betrays the very identity he hoisted as an excuse for sadistic murder. So this time, he is exposed again, this time before Red. I might further like to insinuate that, given the context of this film and Red’s intimidating tool of vengeance, that Jeremiah Sand indeed has ax envy.

Each of these topics are full papers of themselves, and while the film continues with in-references—a mention of Crystal Lake (Friday the 13th)—the stylization is what overwhelms and makes us ask questions. Can we assign meaning to the colors? Is this a modern day fairy tale/fantasy? Let’s look to the colors.

Colors and Planets

Colors that figure prominently in this film are reds, pinks, blues, and yellows. Mandy’s favorite planet is Jupiter, and Red’s is Saturn. Red’s vengeful side would prefer Galactus, Eater of Planets. At minute 7:25, we turn to Red and Mandy in bed under a filter of blue for their planets and colors pillow talk. According to the A Dictionary of Symbols by J. E. Cirlot, “blue (the attribute of Jupiter and Juno as god and goddess of heaven) stands for religious feeling, devotion and innocence.”[4] Through the very colors we are getting a communication of their devotion and innocence to each other. As they speak the filter turns to pinks and reds. Again, according to Cirlot’s researched definitions, “red (the attribute of Mars), passion, setiment and the life-giving principle” with pink meaning “pink (the colour of the flesh), sensuality and the emotions.”[5] Then, we see at minute 11:40 Mandy associated with the color yellow, “yellow (the attribute of Apollo, the sun-god) indicates magnanimity, intuition and intellect.”[6] She comes upon a dead lamb in the woods as if she comes upon a slaughtered sheep. In her readings she is intellectual. In this moment, I am tempted to turn back in the same dictionary to page 53 to note that “yellow, the colour of the far-seeing sun, which appears bringing light out of an inscrutable darkness only to disappear again into the darkness, for intuition, the function which grasps as in a flash of illumination.”[7] Reading just that much further into it is to note the instance of a tiger on one of Red’s baseball tee-shirts and later in the LSD maker’s den. Jupiter with its orange and white bands might represent in some fashion the tiger, but again, that may be reaching too far.

So, I am going to pull back from the deep analysis attempts and admit that the pacing toward the last fourth of the show began to tire me, but it was worth it for the overall effect of this art. And what I might argue is that the slower pacing of the film tells us that there is more to read here. It’s not just about the thrill. All the same, it is a novel of a wrong and a mostly unchallenged revenge. By the time we get to Red’s bloody tirade against the evil, we earned it with him behind the pages of Lenora Tor’s The Seeker of the Serpent’s Eye, which for all of its symbolic messages and homage even gave us sacrificial daggers and magic horns to bring out its hybrid of Road Warrior and Cenobite denizens who would crumble against the unforgiving power of love.

References

[1] Valorum, “What is the extent and nature of Nix’s power in (the film) Lord of Illusions?,” Stack Exchange: Science Fiction and Fantasy, forum, July 25, 2014, accessed September 18, 2018 from https://scifi.stackexchange.com/questions/64041/what-is-the-extent-and-nature-of-nixs-power-in-the-film-lord-of-illusions

[2] Lloyd, Nigel. “Clive Barker – Lord of Illusions,” SFX, No. 16, 1996.

[3] Trepniak, Antony, “The Myth of The Wicker Man,” Necronomania, December 6, 2013, accessed September 18, 2018 from http://necronomania.blogspot.com/2013/12/the-myth-of-wicker-man.html

[4] Cirlot, J.E., A Dictionary of Symbols: Second Edition, (New York: Dover Publicaitons, 2002), 54.

[5] Cirlot, Dictionary of Symbols, 54.

[6] Cirlot, Dictionary of Symbols, 54.

[7] Cirlot, Dictionary of Symbols, 53.

2 Comments

Leave a Reply