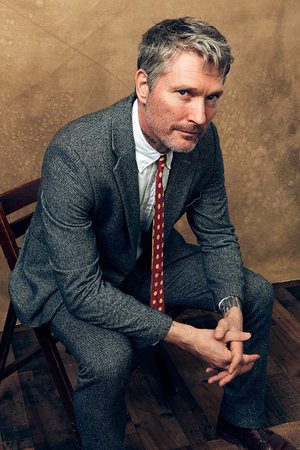

A Wounded Fawn is a film quite unlike any other that I’ve seen in the way it combines Giallo aesthetic with modern gender concerns and ancient abstract symbolism. I had the absolute joy of spending half an hour with its director and co-writer Travis Stevens recently, along with the two leads who he asked to include, Josh Ruben and Sarah Lind, who played Bruce Ernst and Meredith Tanning respectively.

As you might imagine from a description like that above, the interview merited a little homework; though unexpectedly, that homework raised a subject I had to get out of the way first. Back in 1997, Travis had been an extra in Paul Verhoeven’s wonderful Starship Troopers, so I broke the ice by asking how on Earth that happened. All my guests laughed at that.

“I’m so happy we’re starting the conversation with that subject,” said Travis. “When I moved to Los Angeles, I had a piece of paper declaring I had a degree in filmmaking, and I thought ‘I’ll show this piece of paper around town and make films, that’s surely how it works!’ Apparently, my little hippy college on a hill in Vermont didn’t quite understand that is not how it works. So in looking for any way to work in films, I started doing extra work to be around it and ended up being on Paul Verhoeven’s set. Being such a fan of Total Recall and Robocop, I thought, ‘This is great! he’s making some kind of Star Wars film?! This is awesome.’ But then while I was there, the feeling changed to, ‘Why does everything look so plastic?’ and ‘These actors don’t seem any good.’ When we saw the movie, of course, it was clearly a f*cking masterpiece. So it does actually bring me a lot of joy that I wormed my way into that man’s universe on screen.”

Interestingly, I had also interviewed a director whose early career had included special effects work on that very same film: Starship Troopers is clearly an experience people look back on with affection (and fans with envy).

Coming on to A Wounded Fawn, though, I declared my classical ignorance and asked whether Travis might explain the title of the film. He tried giving the others a turn, which this time had me laughing:

“I wouldn’t dare, Travis,” said Sarah.

“I thought it had something to do with Bambi,” said Josh.

And it went back to Travis, as I insisted that he educate me. “It’s a literary reference to a stanza that appears in a Greek play, and also later on in the film,” he said. “I thought it was interesting because an audience will come to a film about a male killer and a female victim with a certain preconception about which of those characters is the prey and which the predator. And I thought that your understanding of who the fawn is in this title would change, making it a more interesting film.”

Travis was one of two writers behind A Wounded Fawn, the other being Nathan Faudree. I asked Travis what his part in that process had been. “The original writer, Nathan Faudree, had written a script called The Furies, about Bruce and Meredith going to a cabin where Bruce kills Meredith and the Furies show up; basically, the concept for the film was his. My part was finding a way to recontextualise those elements in a world that felt thematically interesting to me; finding a way to bring the Greek element into the narrative in a more meaningful way than just the Furies showing up like superheroes, and trying to find a way to add a bit more to Meredith’s back story and Bruce’s approach to life. So it was really working with the framework that Nathan had provided to find my own personal way into the story.”

Travis had collaborated with other writers in his previous two films as director, Girl on the Third Floor and Jakob’s Wife, and indeed other composers and cinematographers too. I asked him whether he had chosen according to each project’s requirements or whether an ongoing team had simply not been formed to date. “I think I grew up thinking a musical band had to be the same members,” he considered, “and when I watched a documentary on The Cure, I understood that each album has different needs, and you can bring in players who add their own tonality to that album: that’s an equally viable way to go about making something. I think in the movies I’ve worked on so far, each movie may need a different tone to it, and so that has motivated some decisions about working with different people. But I am incredibly proud of everybody’s contributions to this film and the films I’ve made in the past, so it’s no reflection on them if we didn’t work together on every movie.”

Sounds like there are people Travis would work with again, given the chance. “Let’s say Josh and Sarah have passed the test,” Travis said with a big smile, though I didn’t think he would have invited them to this interview if they had not!

“Yes!” cheered Josh… and I turned my questioning to him. Josh played A Wounded Fawn’s killer, and I asked him about the process of getting into that unsavoury mindset. “It was tragically easy,” he confessed, “and unfortunately fun. What many actors say about playing the villain is that it’s the most fun and colourful part of these projects. It was great fun because I love to take swings and risks, and it wasn’t just about twirling the moustache and playing ‘evil’ necessarily, as there were many facets to him. The real challenge was playing a version of myself that was as grounded as possible so that the scary stuff really was scary. I’ve talked about playing a seductive version of myself because that’s so much of what this character does, and that was probably the most challenging part.”

Bruce isn’t a caricature in any way, so I guessed Josh had needed to rein in the “fun” aspect of his performance. “Yeah, truly,” he agreed. “I think the research was really done in examining the types of egotistical and mansplaining toxic men that I know in my life, or that I know through friends; how they peacock to impress, or how they feel peacocking is impressive, when in fact you’re just rattling off fancy names and titles of books or art. It was fun to exploit that type of character because it’s a squirmy personality, and unfortunately I think it’s a lot of men. Certainly, a lot of us in the entertainment field know many, but in all fields, the mansplaining know-it-all is out there, and many of them have that seductive quality that makes me squirm. So that was both the fun and the challenge of it all.”

Travis came in with a comment that he hadn’t found the chance to express before. “When we talk to the actors about those two characters, Josh’s character is both presenting a version of himself to Meredith, but also there are moments when he is by himself, responding to things he sees or are in his head. And Josh, I’ve not found the chance to tell you just how f*cking good you are in your performance of those two versions: you really did an incredible job.”

Josh was clearly a little humbled. “That’s the beautiful part about a project like this,” he said. “There’s the writing and playground in which you can do that with different textures and different characters. It was the same for Sarah and all the Furies: we all got to play multiple versions of ourselves and our characters. There’s something really special about playing alone, too: you’re playing a character who is x, but you also play that character when they drop that veneer.”

It wasn’t just Josh’s own role that had some nuance, but his counterpart: for the latter half of the film, he wasn’t playing against a woman so much as abstract representations of female vengeance. I asked what challenges that brought him. “Squirming under their thumb and under their power was great fun, and certainly fun in the context of an unflinchingly insistent character; someone who insisted they were right in a way that—I don’t want to say ‘men,’ but let’s say in the context of today’s world, there are a lot of groups, sets, and demographics that are insistent that a cultist way or a nefarious way of looking at things is the right way, and that’s just their reality. They do terrible things because they insist it’s the right way: ‘That’s how we’ll save America’, or ‘I’m correct, no matter what.’ That’s what Bruce is like, unflinching to the point of self-flaying: he’d rather do so as opposed to admitting he was actually in the wrong. That was great fun to play: a challenge, but exciting because it’s cathartic. I’m sure Travis feels the same because we’ve both made films about bad men; there’s something cathartic about going after someone who we’d all like to see raked over the coals, whether they end up admitting their wrongs or not.”

Josh’s and Sarah’s characters both were “types” but also represent their sex to a degree, and were nevertheless full of nuance. I asked Sarah how she approached her character, with its interesting twists to the hunter/hunted dynamic. “In some ways, it’s two different characters,” Sarah mused, “and in some ways, it isn’t; especially depending on how you interpret what’s happening in the latter half of the movie. (And there’s no right or wrong there.) The sharpest peak of Meredith’s arc happens prior to this movie and she’s wrapping it up, so in some ways, this is an epilogue, or perhaps a continuation of another story. I find her arc to be particularly shallow because she’s learned these lessons; I don’t mean shallow in a bad way, but even though she transforms, she doesn’t go through a personal transformation in a way that characters do in many other stories, because she has done her learning already. I think she goes into this weekend with her eyes open, she is noticing red flags and is choosing to continue with the date; I’m not going to judge if she does right or wrong in those choices, but they’re realistic, in a large part because she’s being tricked.”

I think Meredith did what she could in response to those red flags. “I think so too,” Sarah said, “and when it gets too much, she says, ‘That’s it, let’s leave,’ but of course, it’s too late then. But the way we see her at the end of the movie is sort of where she started: people like you can go f*ck yourselves. I don’t mean to spoil anything, but that’s basically it: ‘This is on you,’ she says. ‘It’s your job to fix yourself and take responsibility, and it’s not my problem.’ I thought it’s an unusual shape for a character’s trajectory, and I really loved that a lot of the fun in the movie is in the building up: each red flag builds up on the last, they don’t get forgotten or missed, but she clocks them, thinks, ‘That’s weird,’ and determines whether to continue. Then of course she can’t take anymore and all Hell breaks loose.”

At the start of A Wounded Fawn, Meredith had not long left an unhealthy relationship. I asked Sarah whether she felt Meredith’s story might have turned out differently with a less dramatic backstory. “It may or may not have,” she said. “I’ve been listening to podcasts and watching shows about cults and cult survivors, and an interesting thing that crops up is that there’s no psychological profile for someone who is more or less susceptible to be drawn into a cult or a high-demand group. Anyone can be tricked if they get to us in the right way. And I think it’s an interesting take that she’s not naïve, she’s not a babe in the woods; she may have been during that earlier relationship, but at this time, she still got tricked, even with no naiveté. She did the best she could and still fell into it again. It happens, unfortunately.”

Travis had been keen to include that back story, so I asked him how important it was. “I think the way A Wounded Fawn ends is predicated on the fact that Meredith had done the work, that she had done before this story. Whether it’s overt or not in the narrative, Bruce represents this super-predator, this person whose power to achieve his goals comes from his ability to get people to let their defences down; then part of what the movie is doing is testing Meredith’s defenses. What’s happening here is that she is trying to evaluate whether what her intuition tells her is valid, or if she is being overly paranoid; and I found that to be an interesting dynamic between these two characters, where the audience knows what Bruce is doing, but Meredith doesn’t. It’s like we’re watching these two chess players, where we understand each one’s strengths and weaknesses; so to me, it’s her having successfully identified and gone through the therapy from an abusive relationship in the past is super important to get this story working.”

I couldn’t help but notice that each of Travis’s films so far as a director had all touched on themes relating to the battle of the sexes to some degree, which raised a couple of questions. Firstly, I asked him whether he felt this conflict was part of nature, always destined to be with us. “I hope not,” Travis answered firmly. “My own understanding of the relationship between the genders has been growing and improving, and I feel like I have seen that on social media, and in the way people talk about relationships and problems in relationships, it feels like the dialogue is getting more informed. Our understanding of needs and wants and how those can come into conflict with our partners…it seems to be evolving in a positive way. Certainly, the conflict has been a part of humankind’s existence so far, and I wouldn’t presume that it will disappear, but it does seem that we’re making progress toward being able to address it and confront it in a healthier way. That could be any kind of conflict: I wouldn’t just limit that observation to the gender conflict.”

Of course, conflict is the stuff of drama, after all, and therefore has a perfect home in the stories we tell. As an agender person, I have a curious perspective on such stories, and I asked Travis whether he felt there was a place for non-binary characters in such dramatic conflicts. “I feel that it’s in this film,” Travis answered, “subtly, of course. For the character of the Red Owl, which is a manifestation of one aspect of Bruce’s personality, it was important to cast a non-binary actor in that role; and I feel that character at least introduces that colour to this canvas and to horror in general. It’s certainly not my place to make that the focus of the movie, but I think this is the world we live in, and we should be bringing in as many of those colours that we see in our world into our art.”

I had seen quite a few films in recent years that look at resilient women, often finding an escape from controlling men; and I’m never quite sure how to feel about those that are written by men. I asked Travis whether he had any female collaborators lined up. “I really appreciate that question,” he answered, “and I’m curious to hear Josh’s and Sarah’s responses as filmmakers and actors too because I have seen that feedback from critics and audience members: ‘How dare you presume you can tell this story?’ And that’s interesting to me because you always try to tell a story from your own perspective, even if you’re not one of the characters in the story. To me, of course, someone who identifies as male can tell a story with their perspective on those characters; and as someone who’s done some work on myself in this lifetime, I feel I do have something to say about the way men and women relate to each other. On Jakob’s Wife, Kathy Charles had done a draft which brought some aspects that made that movie better, and I’m open to working with anyone who has a good story to tell. I think in indie films, you tend to just do the work that gets you to the next level; it’s not always dictated from choice. But do I want to work with more writers? Of course.”

I returned to my other guests and referred to the abstract nature of the script: how on Earth did Travis sell it to them? “He just handed it to me,” Sarah answered bluntly. “I read it, I liked it, liked what I saw of Meredith on the page. I liked how many ideas instantly started sparking when I read it, and furthermore, the wild images that you see in the film were detailed pretty explicitly in the script, so it was really exciting to imagine them and want to be part of this whole piece. I loved it as soon as I read it.”

“Same,” said Josh. “Travis handed it to me digitally over Twitter DM and I read it immediately. It was the same exact thing: especially as a fan and a filmmaker, the early work of Sam Raimi was called up in the visual style inherent in the script itself and in the character. The fact that it was a feminist story and dealt with the gender dynamic was important to me as well: you don’t see a lot of that, whoever the filmmaker is. It was an art project, essentially, that I wanted to be a part of; a wonderful way to spend the fall season on the east coast.”

The rich colours Josh had hinted at reminded me of a comment our writer Timothy (who had reviewed the film when it screened at Fantastic Fest) shared with me. He felt that Travis had “nailed the feel of ‘70s horror” and that “between the color palate and set designs and performances it honest to god felt like a long lost contemporary of Suspiria and Messiah of Evil to the point that I had to double-check the release date against IMDb at one point.” I had to share a compliment of that nature and then asked Travis why he had chosen to present his story in that way. “When I imagine the movie in my head, it has that texture, that quality of those movies from the seventies and eighties; the production design, the wardrobe, the acting, the camera all working in harmony in a way that I sort of miss. It was sort of exaggerated back in the seventies and so in conceiving this story because we were going to get into the characters’ heads and how they perceive the world and because those perceptions were going to get exaggerated, it seemed to make sense to give the film that seventies or eighties aesthetic; the Euro-sleaze, Argento, Bava, Fulci quality to it. So it’s really exciting to hear people respond to that, get excited about that and feel that’s there cohesively, not just in one shot but in the movie’s DNA, because that certainly was the intention.”

Timothy had also said he thought A Wounded Fawn was probably the best horror film he’d seen all year. I asked my guests what they felt was the best film they’d seen this year. “There’s been so many,” mused Josh. “Actually, my absolute favourite is one that hasn’t come out yet but played at Beyond Fest: it’s called Sick and was written by Kevin Williamson of Scream fame, directed by John Hyams who made Alone and one of the Universal Soldier pictures that was apparently very, very good. It was probably one of the only times I’ve ever screamed at the screen and really shout-rooted for a protagonist; I like to go for as much variety as possible watching genre and I thought that was so fun. I’m so excited for everybody to see it; it was so paced up and visceral. I think there’s one that most people have seen actually and that’s Halina Reijn’s Bodies Bodies Bodies. The ensemble was amazing; take a comedian like Rachel Sennott just as an example, and put them in a scenario where they can really play terror and catharsis and fear, and a female production, and have it just as fun and brutal as it was… that’s really exciting.”

Sarah decided to give me two favourites too. “Not to be basic, but Barbarian had me yelling so much in the theatre; it just got me hook, line and sinker and as it smashed to credits, I laughed my head off. It was so funny; and all that hallway stuff, going through six different hallways? Not that I was laughing at all while that was happening, because I was truly, fully on the line for that; then once the thing came, I completely lost it. Then another movie we saw at Beyond Fest was Kids vs. Aliens. It was so funny, so thoroughly entertaining, just fun, fun, fun; and also that rare thing of kids acting as kids, rather than acting as child actors (and I was a child actor, so I’m allowed to say that). The kids’ performances were so true, so full of imagination; that movie was an absolute gas.”

I wondered whether Travis’s favourites were a little more serious. “Actually, I think one of the things I’ve enjoyed most about all the horror movies we’ve seen this year,” he said, “is that they have a sense of fun or playfulness about them. And I’m excited that it seems we’re in this moment where people are getting the opportunity to make movies where the unexpected happens, and I’d say Malignant was the start of this, ‘Hey, let’s put crazy sh*t in horror movies!’ But I guess if I had to pick one, it would be Pearl. I was really impressed with it; not that it was the scariest horror movie of the year, but for Ti West as a filmmaker to have reached that point where that’s the movie he wanted to make, was able to make, and made that well, I found really satisfying. And maybe we are in a new age of horror where it can really be any sort of style.”

At the time of this interview, A Wounded Fawn was soon to arrive on Shudder (and now has). I asked how all my guests felt about this prospect. “I’m so excited,” said Sarah. “It’s not always the case that one truly loves and is proud of something you’re promoting, but I genuinely love this movie and I’m so blown away by everything about it. I’m proud of Travis, and Josh just kills it, brings such a new thing to this character. I’m so excited for everyone.”

“Hasn’t sunk in yet,” said Josh, “but I think that feeling is mutual. We’re all so proud. It is rare indeed to feel this proud of something, but it’s special on many levels. I think it’s going to have quite a life to it.”

“I’m so grateful to Shudder,” said Travis, “for giving us the opportunity to make the movie because they saw the potential in the script and said, ‘Yes, let’s make it together,’ and they did a great job in introducing it around the world to festivals and now bringing it to the small screen. Of course, you’re always nervous about how it’s going to play to the general public, and whether or not people like the film may vary, but I know there is something of value that everyone will get from the film; whether it’s the costumer’s contribution, the composer’s score, the actors: there’s a lot of movie in this movie.”

Or that ending, I suggested! “Yeah, the end credits,” Travis laughed. “How many times can I hear ‘You’re going to love the end credits!’ I think no matter what, there’ll be something on that table that a viewer will enjoy.”

Each of Travis’s three films has been received very well. I asked where on Earth he plans to go next. “I would like to make a movie with a male character who is maybe a good guy,” Travis said. “Let’s see what that’s like. I just want to make movies with people I respect and perhaps bring something of value to the world.”

Travis Stevens’ A Wounded Fawn is now available on Shudder, as is Josh Rubens’ new film Blood Relatives (as Josh told me, “you can watch that one with the kiddo”).