When I grew up in the 1980s, things were very different than they are today. Kids played after school until bedtime with little adult supervision—we were simply told to be home when the streetlights came on. We could cover miles on our bikes and be out of contact with our parents for hours and no one thought anything of it. Growing up in America’s heartland magnified this freedom. We had the idea that nothing ever happened in our sleepy towns and that we were immune to “big city” problems. The innocence of that life all changed with what happened to Johnny.

The Missing Paperboy

John David Gosch was 12 years old when he was abducted while delivering newspapers at 6:00 AM, Sunday, September 5, 1982 in West Des Moines, Iowa. Johnny was a well-liked boy from the neighborhood who was a Cub Scout, made friends easily, was close with his parents, and loved his little dog, Gretchen.

As the story goes, Johnny left the house that morning with Gretchen and his red wagon to go to the corner and pick up his papers for his route. His father, John, usually went with him on his route on the weekends but wasn’t present on this particular morning. Everything seemed normal until a phone call came from a neighbor asking why their paper was late. John Sr. went out to look for Johnny but found only Gretchen tied to his wagon with his papers. These were things Johnny would never voluntarily leave behind.

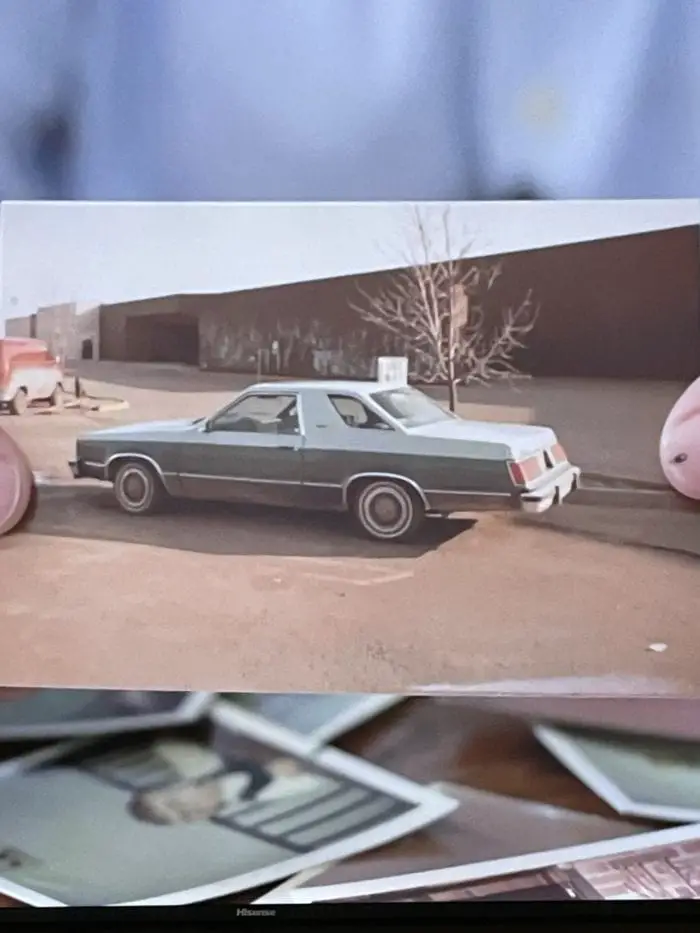

Upon returning home, John Sr. told his wife, Noreen, the news and they called the police to report Johnny missing. The West Des Moines police took 45 minutes to show and immediately asked if Johnny had ever run away before. His parents were adamant that Johnny had not run away but was abducted. That was corroborated by the other paperboys from the area who said that someone in a two-toned Ford Fairmont was asking Johnny for directions. Another neighbor also reported seeing a car running a stop sign and speeding away from the area.

Five witnesses saw this abduction take place, yet police insisted Johnny was a runaway. “There was no crime scene,” said Captain Bob Rushing of the West Des Moines Police Department (1973–2001) in the 2014 documentary, Who Took Johnny. “Nobody saw what was, to us, an explanation for the boy’s disappearance—he just vanished.”

Noreen Gosch told the documentary filmmakers that while thousands of people canvassed the area searching for her son, nothing was organized by the police, and the FBI was never called as it remained their position that there was no crime. “We were told by government agencies that you have to prove the child is in danger. ‘To us, he’s a runaway until you prove he’s in danger,’” Noreen said. It didn’t help that at the time, police policy was to wait 72 hours before investigating any reports of missing children or that Noreen was seen as “abrasive” by the police due to her dogged nature of pushing them to investigate her son’s disappearance.

On August 12, 1984, just under two years after Johnny’s disappearance, another paperboy was taken from the same town. Eugene Martin was just 13 years old when he also was abducted while delivering papers in the early morning. He was reportedly seen talking to a man in a car. No evidence was found at the scene except his folded newspapers that were left behind. The unthinkable had happened again, yet police said the two incidents were not connected.

Determined Parents

Noreen Gosch was no stranger to tragedy. She married at a very young age and had two children with her first husband. One night a tornado came through their small Iowa town, and she was separated from her children. She later found them face down under some debris. Luckily, they survived, but her husband passed away just two weeks later from cancer. She met John Gosch, Sr. approximately two years later, married, and the two had Johnny. Unfortunately, the toll of their son’s abduction wreaked havoc on their marriage and they divorced 10 years after his disappearance.

While together, the couple fought tirelessly to find their son while helping others find their missing children. They were even instrumental in starting the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children in 1984 with John Walsh whose son, Adam, was abducted and later found murdered.

On July 1, 1984, the Gosches were present when the Johnny Gosch Bill was signed into Iowa law requiring law enforcement to act immediately when a minor is reported missing rather than waiting 72 hours. In September of the same year, a local Iowa dairy began the trend of putting photos of missing children on milk cartons with Johnny Gosch and Eugene Martin being the first children pictured.

In the more than 30 years since her son’s abduction, Noreen has worked to keep his story alive, appearing on television, in documentaries, and counseling parents of other missing children.

A Horrific Scenario

In 1985, the Gosches were notified of a $1 bill that was received by someone across the United States that bore a handwritten note saying, “I’m alive,” signed by Johnny Gosch. In 1986, another child, Marc Allen, disappeared under similar circumstances to Johnny and Eugene. Children continued to disappear, and police were still unable to find any leads.

Later that year, the Gosches were contacted by child safety expert, Kenneth Wooden. He was of the mind that Johnny may have been the victim of a human trafficking ring of which he had been made aware. While Noreen had never given up hope that her son was still out there alive, this was not a hypothesis that any parent would want to entertain.

In 1991, an inmate at the Nebraska Department of Corrections, Paul Bonacci, confessed to his part in Johnny’s abduction. He said that he was a victim-turned-perpetrator in a child pornography/trafficking ring out of Omaha. Police were not interested in taking the word of a convicted sex offender, but Noreen was keen to hear him out.

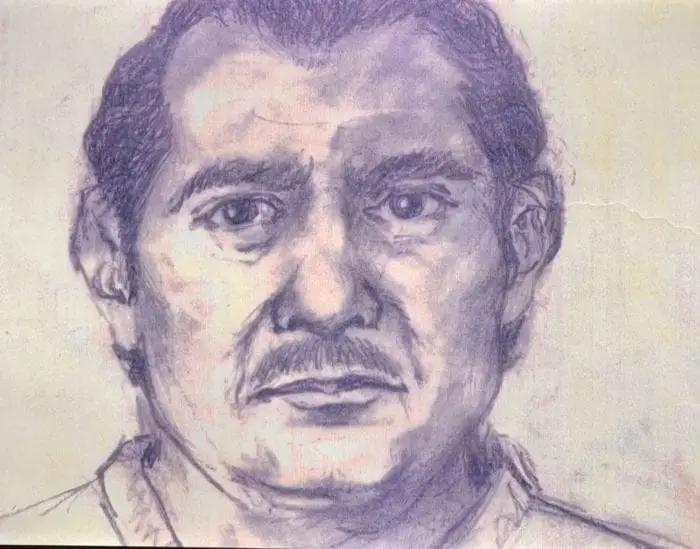

Bonacci and Mrs. Gosch met in person at the correctional facility where Bonacci provided details about Johnny that only a person who had seen him or his family would know including describing a birthmark on Johnny’s chest and various scars on his body from childhood accidents. Bonacci explained that the traffickers, including a man named “Emilio” who matched the description of a composite sketch done soon after Johnny’s disappearance, targeted children who “weren’t used” and were close to their families. He also admitted to his part in kidnapping and grooming Johnny for his part in this trafficking ring. While police paid no mind to Bonacci, Noreen was re-energized in her search for the truth.

In 1992, America’s Most Wanted profiled the Johnny Gosch case again and people began coming forward with sightings and information. Still, neither Johnny nor Eugene have ever been found.

The documentary, Who Took Johnny, delves further into this child trafficking ring and the assumption that Johnny is now or was a large part of that. It also explores Noreen’s assertion that she was visited by her son and another boy for a couple of hours but that she never reported it to the police for fear of his safety. She also reported receiving photos and letters from an anonymous source showing Johnny and other boys bound and gagged.

Who Took Johnny is available for rent on Amazon Prime.