Trigger Warning: this article makes reference to rape, sexual assault, paedophilia, violence against women, pregnancy, racism, classism, and gore.

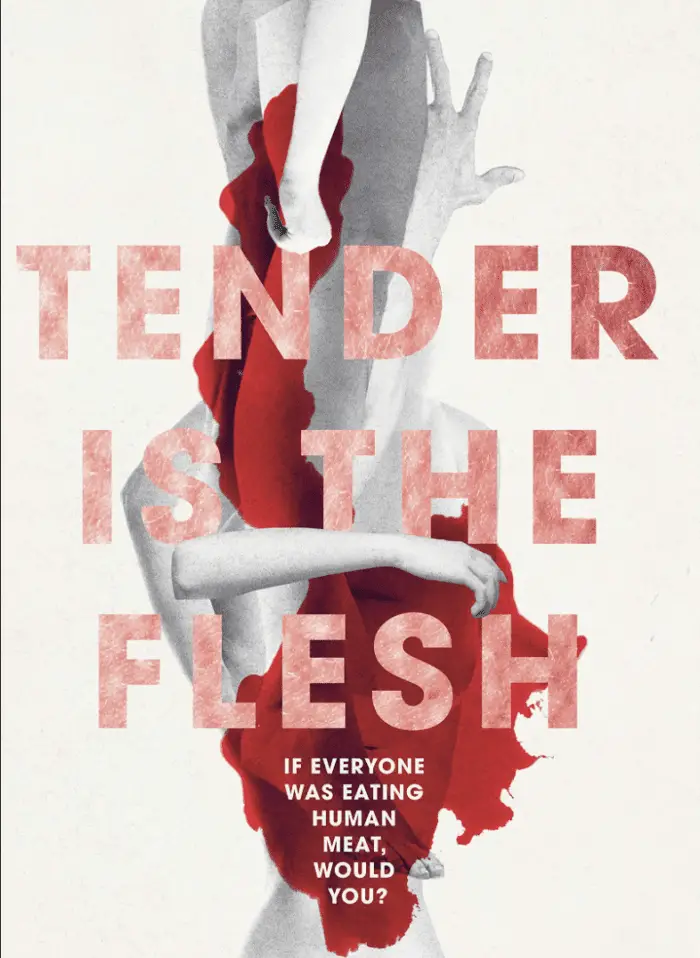

Tender is the Flesh is a 2017 novel by Agustina Bazterrica set in a dystopian world where cannibalism is legal. The background for this is that all animals have been infected by a virus fatal to humans, therefore their meat can no longer be consumed. Instead, humans have resorted to eating the only source of meat: other humans. Extreme yet straightforward, the concept lends itself to a multitude of themes and prevalent political commentary. Despite the obviousness of this, the discussion of such themes doesn’t feel particularly heavy-handed at any point during the novel.

The Meat Industry

First and foremost, the massively textual commentary is on the meat industry. Veganism/vegetarianism is an obvious alternative if humans are unable to eat animal meat; however, it’s pretty much immediately ruled out. An offhand comment in the first few pages acknowledges how the ‘Transition’ (the term used to refer to the changeover to eating human meat) was a “revenge of the vegans.” But shortly afterward, groups turned to capturing and eating people on the streets, which spiraled into cannibalism en masse. It’s interesting how there aren’t really even any vegan protest groups involved, but excluding this aspect serves a narrative purpose more than anything. If veganism was a viable option, then cannibalism couldn’t be explored as a societal norm.

Legalisation of cannibalism, as explained via exposition, occurred only once a “big-money industry” put pressure on the government. It wasn’t long after this that humans were bred to produce meat. This immediately sets up a direct link between the meat industry and capitalism. Businesses and CEOs making a profit are the sole reasons for this industry. Good business practise and animal (or in this case, human) welfare is never the priority. The processing plants in Tender is the Flesh are focused on harvesting high-quality meat, rather than cultivating good conditions for the ‘Heads’ (the term for humans bred for meat).

Again, there isn’t really any reference to resistance groups or animal rights activists pushing back against the bad conditions of the processing plants, at least not from the perspective of our protagonist, Marcos. It’s a very cynical angle, almost as though everyone in this new society accepts the Transition and inherently knows that nothing can cause things to revert back to how they were. Further cynicism is conveyed via references to a government conspiracy. It’s implied multiple times across the novel that the animal virus has been fabricated, and cannibalism implemented as a means of population control. This makes the whole situation far more bleak and hopeless.

There’s even an element of voyeurism, as represented in one of these circumstances. A man goes in for an interview at the plant Marcos works at but is discovered to be recording footage of the Heads while on an initiation tour. This is for his own viewing pleasure. He repeatedly expresses a morbid fascination with the Heads and the violence committed against them. Even once he’s caught and kicked out, he has no remorse for his actions. It’s this kind of psychopath that revels in the killing of fellow humans that is represented far more than those with empathy throughout the novel. Everyone is inevitably complicit, if not actively indulging in cannibalism and violence.

Narration, Style, and Characters

Stylistic choices of narration in Tender is the Flesh reflect the world it’s set in as well as how people interact with it. The writing style itself is rather straightforward and easy to read, but with significant abstract elements at the same time. A lot of the description is heavily focused on sensory input, emphasising the idea that feelings are the only thing that matters anymore. Here is the opening of the novel:

Carcass. Cut in half. Stunner. Slaughter line. Spray wash. These words appear in his head and strike him. Destroy him. But they’re not just words. They’re the blood, the dense smell, the automation, the absence of thought.

Instantaneously, the concept of words having a visceral impact is established. To add to this, there is a lack of dialogue across the entire novel, but especially in Part One. Prefacing the novel is a quote by Gilles Deleuze: “What we see never lies in what we say.” Combined with the lack of dialogue, this highlights the hypocrisy of the characters’ words. The moral ambiguity of the post-Transition world is shown through actions and contradicted by direct speech.

Interestingly, words are presented as the primary way in which Marcos, and therefore the reader, infers character. For example, when Sergio (one of Marcos’ colleagues) speaks, his words are described as “clean, with no sharp edges.” The reason Marcos respects Sergio is that he’s genuine and down-to-earth, which can be gleaned from this description. In contrast, Marcos communicates during a conversation with the butcher Spanel that “her words drive at his brain”; that they’re “frigid, stabbing.” Spanel is extremely emotionally detached and calculated, but intense in her interactions with Marcos, which these adjectives convey succinctly and effectively. In this way, the feel of people’s words is far louder than their actual dialogue.

Two characters who embody two distinct reactions to the post-Transition norms are Urlet, a wealthy businessman and hunter, and Marisa, Marcos’s sister. We don’t meet Urlet until the second half of the novel, but he certainly makes an unforgettable impression. Marcos has to meet with him out of necessity, but makes it apparent from the get-go that he despises Urlet. The way in which Urlet is described is utterly fascinating: as having abnormally long nails with “an ancient presence to them,” that there’s an entity of some kind inside him, “clawing at his body, trying to get out.” He’s like a vampire, feeding off the souls of the humans he consumes.

Urlet is a highly indulgent individual, living in luxury and dining on fancy foods. His excessive wealth is evident, and means he’s above the law in a way. He left Romania because hunting game for sport was outlawed there, and wanted to maintain his business. So, a pretty immoral guy. The language used when Urlet describes eating human meat is extremely reflective, philosophical, and rich:

There’s a vibration, a subtle and fragile heat, that makes a living being particularly delicious. You’re extracting life by the mouthful. It’s the pleasure of knowing that because of your intent, your actions, this being has ceased to exist. It’s the feeling of a complex and precious organism expiring little by little, and also becoming part of you. For always. I find this miracle fascinating. This possibility of an indissoluble union.

Obviously, this is horrifying to read. However, the seductive language draws the reader in so you almost believe him. You almost want to feel what he feels, that utter hedonism and sensory pleasure he experiences, so far removed from any guilt or shame. It must be a liberating way to live. As opposed to everyone else, he allows himself enjoyment.

Later in his conversation with Marcos, Urlet explicitly says he has no moral dilemma with cannibalism. In fact, he claims that “the Transition has enabled us to be less hypocritical,” as according to him, “since the world began, we’ve been eating each other.” Again, it’s difficult not to agree with his perspective here. In metaphorical terms, humans have been consuming each other, through war, through capitalism, through acts of selfishness and unkindness. Urlet is simply being upfront about it. It’s an accurate statement to say he’s the least hypocritical character in the entire book, and in that way, he’s admirable.

In contrast, we have Marisa. She is a cannibal, like pretty much everyone in the novel, but is under pretenses about it. When having dinner with Marcos and her children, she scolds her kids for inventing a game of speculating about what people taste like. As she says, “We don’t eat people. Or are the two of you savages?” This is a blatant lie, but the language is very specific, speaking louder than the surface-level sentence itself. The implication of “we don’t eat people” is that Heads aren’t people; therefore, Marisa is dehumanising them to make it easier to justify cannibalism to herself.

Later on, Marcos discovers that Marisa is keeping a Head inside her house that she’s eating gradually, serving up part of the meat for dinner guests. When she notices her brother heading to the back, towards where she’s keeping the Head, Marisa tries to stop him. She clearly knows what she’s doing is wrong, otherwise she wouldn’t try to hide it. Via the narration, we’re also told at this point that “domesticated Heads are a status symbol in the city.” So, Marisa must have told some people about the Head she’s keeping, as she cares deeply about social appearances. She’s aware that Marcos is completely apathetic towards societal norms, which is ultimately why she keeps the Head a secret from him. But also, she doesn’t show it off to guests, because who wants to look at the creature they’re eating? In this way, the Head represents Marisa’s conscience, kept locked away, out of sight, so she can keep living in blissful denial.

From a psychological standpoint, it makes sense that Marisa would be trying to convince herself that what she’s doing is acceptable. It’s out of self-preservation. Any characters throughout Tender is the Flesh who become too aware of morality and condemn the treatment or consumption of Heads don’t get a good ending. For example, there was a man called Ency who used to work at the processing plant, but started to get physically ill and withdrawn as he gained empathy for the Heads. One day, he attempted to free them all by opening their cages. The ones that left got captured again, so his actions only resulted in him getting fired. After that, he committed suicide. Ultimately, any acknowledgment and attempted action regarding morality does nothing to deconstruct the society or help the Heads, but only negatively impacts the mental well-being of the individual.

So, even though Urlet and Marisa both participate in the societal norms of cannibalism (and take it even further than that), Marisa makes transparent attempts to justify it to herself and others. Ironically, this makes her more of a hypocrite, and arguably less likeable as a character.

Marcos

Stuck in between these two extremes is Marcos, our protagonist. In terms of his personality, he’s rather a blank slate, at least in Part One. He comes across as very aloof and emotionally detached; any offense or emotions incited by interactions with other characters just slide off him. His sense of self feels irrelevant to his character. Until 52 pages into the novel, his name isn’t even mentioned. Additionally, it’s only ever via dialogue that Marcos’ name is brought up. In this way, he only exists via other people’s perceptions of him.

Marcos’ job is another defining feature of himself. He works at a processing plant as the post-Transition version of a butcher. Since the plant is inherited from his father and his only skill is butchery, he doesn’t have much choice in the way of a career. From the first page of Tender is the Flesh, it’s evident that Marcos despises his job and only does it out of necessity. Upon waking each morning, “his body is covered in a film of sweat because he knows that what awaits is another day of slaughtering humans”. There are no two ways about it—his suffering mental state is a direct result of his distaste for his position.

The post-Transition society depicted in the novel is consistently presented as one without much free will. It does exist, therefore individuals are still accountable for their actions. However, most people, especially Marcos, seem to have very easily accepted that they can’t make any major changes or reject their intended roles. There are some smaller yet significant rebellions that Marcos makes, such as being a vegetarian. This shows a certain effort to morally remove himself from the world around him; even if his job forces him to participate in the killing of humans, in his personal life he refuses to consume them. Ultimately, it doesn’t make a difference, but the fact that he tries is revealing of his character.

In Part Two, Marcos is almost a different person. His mental state is very obviously deteriorating, as his behaviour is a lot more impulsive, and he doesn’t shy away from expressing aggression or annoyance towards other people. After his father passes away, his final ounce of restraint is destroyed. He feels utterly dissociated from the expectations and norms of this society. As a result, he lashes out at his sister in a culmination of tension that has been building ever since we were introduced to her. He tells Marisa, “you disgust me,” continuing with an astute commentary on what most people have become after the Transition:

Can’t you see you’re incapable of thinking for yourself? The only thing you do is follow the norms imposed on you. Can’t you see that this whole thing is a superficial act? Are you even capable of feeling something, really feeling it?

His dialogue is a rather on-the-nose observation of social expectations and the adequate reaction. But it’s a realistic outburst of a person feeling the weight of the world they’re in, and displacing that anger onto someone also just trying to survive. Yes, Marisa is a hypocrite, and her behaviour is easy to condemn. However, she’s also your everyday human who isn’t to blame for the messed-up position she and everyone around her is in. It’s naturally much easier to project all your troubles onto a tangible human of a similar status as opposed to an entire society or government. Plus, Marcos is right to call her out considering how her actions have had a huge negative impact on his wellbeing.

The event that communicates Marcos’ downfall the most is his relationship with Jasmine, the Head he was given at the start of the novel without permission. Throughout Part One, he was almost entirely apathetic towards her. He did the basic things you’d do to look after a pet, such as cleaning her and providing food. Then, right before Part Two, he does the unthinkable. Born of his loneliness (separation from his wife) and grief (for his dead son), he displaces these feelings onto the Head and has sex with her. In Part Two, we discover Jasmine is pregnant, and that she and Marcos are now cohabiting in some form of romantic relationship.

We see this entire situation from Marcos’ perspective, so there is some level of empathy with him. His attempts to cling to something substantial, to give himself a purpose that means something to him, are completely understandable. It’s easy to pity him, especially as his reasons are very transparent. Even his treatment of Jasmine can be considered compassionate in a way; he gives her a home, cares for her, trains himself on pregnancy care to give her proper medical care. But that’s about as far as it goes.

Marcos’ actions in regards to Jasmine are extremely questionable. Aside from the fact that having sex (or any kind of relationship, really) with a Head is illegal in this world, Jasmine also cannot consent to sex due to her lack of understanding, so this is technically rape. Marcos never considers Jasmine’s feelings or desires, only projects his own problems onto her in the hope that she can fix them. She has no autonomy in their relationship.

In addition, Jasmine’s lack of human socialisation as a person bred as cattle means she remains in a rather childlike state of mind. Marcos goes about teaching her how to use the toilet, use cutlery, wear clothes, etc., in a way that denotes a parenting dynamic as opposed to two adults on the same level in a relationship. Gender dynamics are hard to ignore in this situation too. A man teaching a human assigned female at birth how to essentially act like a girlfriend or wife to him is a fascinating commentary on patriarchy and expectations placed on how women should behave in order to pass as a ‘normal’ functioning member of society. For example, when Marcos initially made Jasmine wear clothes, she “ripped her dresses, pulled them off, urinated on them.” Humans aren’t naturally supposed to wear clothes; we only evolved to have to wear them for social acceptance. Jasmine’s rejection supports this. Furthermore, Marcos’ specific choice of dresses infers a rejection of traditionally feminine clothing. Again, gendered expectations are an entirely social construct, so this wouldn’t make any sense to a human who hadn’t been taught this from birth.

Even though Jasmine has free reign of the house, in contrast with being kept in the stable like a pet in Part One, she is still a prisoner. The POV of the novel claims that “the mark on her forehead […] forces him to keep her locked up in the house.” Again, Marcos is fully aware he will receive a death sentence if he’s caught, but this places Jasmine in the position of being extremely restricted, removing her freedom and agency. No matter how much Marcos attempts to convince himself and dresses her up, she’s still stripped of her humanity.

Politics

This applies to all of the Heads in Tender is the Flesh, but particularly female Heads. There’s much more attention on them rather than on male Heads. Female Heads are specifically bred to be submissive and utilised entirely for their ‘biological purpose’ of childbearing. This is an exaggerated version of how women are socialised in our world, as they are expected to conceive children, and this is often internalised as the main value of womanhood. Despite the criminalisation of having sex with Heads, there are a few scenarios mentioned of female Heads being used for sex. As previously mentioned, this can be considered rape due to lack of socialisation—Heads wouldn’t understand the concept of sexual intercourse or consent, and even verbal consent is removed since Heads’ vocal cords are removed.

In the instance of a security guard at Marcos’ processing plant, he is explicitly considered a rapist for what he did to a female Head and was arrested for it. One of Urlet’s associates, Guerrero Iraola, brags about his ventures at a seedy club known for human trafficking. As well as sex work, women are also paid to be eaten. These people aren’t referred to as Heads, so there isn’t the same problem of consent. However, the mention of sex trafficking denotes a lack of choice for these sex workers. Furthermore, we discover that the sex worker Guerrero is boasting about having eaten was a fourteen-year-old. This is objectively non-consensual and deeply disturbing on multiple levels.

As discussed, Marcos having sex with Jasmine is still rape but is never labeled as such. Obviously, the circumstances are different, but the principle is the same. Experiencing the events of the novel from Marcos’ perspective also explains why he wouldn’t think of the situation in that way as a defense mechanism.

It’s worth pointing out that the reason why having sex with a Head is illegal and punishable by death isn’t to protect the Heads or condemn sexual assault. The sole reason is to preserve the meat, so it remains high quality and easily profitable. Even in the official law, sexual assault isn’t taken seriously, and the Heads’ (again, more often female Heads’) wellbeing isn’t taken care of. Making money and protecting businesses is once again the priority. In this respect, Bazterrica is making an astute link between patriarchy and capitalism.

As well as feminist commentary, class oppression is addressed via the ‘Scavengers.’ This is a group that are essentially equivalent to the homeless or ‘underclass’ (lower in social status than the working class). Scavengers can’t afford special meat (what human meat is referred to), so they’re driven to stealing what they can get, mostly reject cuts. They’re portrayed, and even directly described as “savage monsters.” This has very problematic connotations when considering the class connection, positioning lower-class people as animalistic and unreasonably aggressive. It’s also extremely hypocritical—all members of society are participating in cannibalism, so why are the Scavengers worse? It reeks of double standards. These people are simply trying to survive, which contrasts the unnecessarily decadence of certain upper class characters (e.g. Urlet).

With gender and class politics also comes race. Although this isn’t addressed as much, Bazterrica does make reference to racism. Near the beginning of the novel, white skin is described as being more sought after in the market, which places darker skin as inherently less desirable. However, Black skin is profitable only when the market demands change. This emphasises the lack of value on Black lives, while simultaneously exposing the fickleness of capitalism.

Urlet also has images of white men hunting black men before the Transition on the wall of his office in a depiction of explicit racism. Ironically, this taking place before cannibalism was legalised supports his point about how humanity has been eating each other since the beginning of time. Black people were no more safe before the Transition, it’s just that hunting them is a little more socially acceptable now. Urlet’s status as an upper class businessman again represents the intersection of racism and classism; his status means he can get away with overt racial oppression.

Ultimately, all political inequalities predate the Transition, but the event serves to expose them. Bazterrica addresses these social issues in a direct, effective manner. She doesn’t claim to be adding anything new to the discussion, or incorporating an original political commentary, but instead uses the concept of cannibalism to explore it in a new context. Her abstract narration emphasises the feeling of emotional detachment from a system seemingly impossible to navigate. Humanity must be removed in order to survive.

The End of It All

This culminates in the final line of the novel: “She had the human look of a domesticated animal.” Marcos says this to justify his killing of Jasmine after she gives birth. It directly mirrors one of the quotes at the start of Part One: “…and its expression was so human that it filled me with horror…” (Leopoldo Lugones). Once any sense of humanity creeps in, it creates a horrifying juxtaposition with the brutality of the world. Stamping it out serves to maintain Marcos’ self-preservation. The illusion of a substitute wife has finally broken for him, and ignorance is the only way forward.

It’s a very fitting ending for a consistently bleak novel. There isn’t so much as a glimmer of hope throughout the whole story. Seeing Marcos become more and more unstable as he makes increasingly disturbing choices is devastating to follow. However, it’s suited to the grim tone. He could be considered a product of his environment, yet it’s still fair to criticise his actions. Tender is the Flesh effectively communicates the malleability of the human condition. Who would have known cannibalism could be so versatile?