Zombies are a cornerstone of our beloved genre, but often the tropes and clichés of the subgenre can grow boring and repetitive. When a film does an interesting job playing on those tropes, like Shaun of the Dead, it can go on to reinvigorate the subgenre—at least, until things feel played out again. The zombie subgenre is definitely not the only one to fall under this curse; slashers, found footage, and everything in between has the same issue. There comes a time, though, when the idea of what a subgenre can be gets completely flipped on its head. Though, unfortunately, in this case, it seems to have gone largely unnoticed. Today, I want to take a moment to shine a light on one of my all-time favorite zombie movies, taking a look at how it came to be, what it was, and where it’s going. Let’s take a look at the three (and a half, with more to come) mediums of the world of Tony Burgess’s Pontypool.

In 1995, Tony Burgess released a zombie novel that would go on to spawn a film adaptation, a radio stage play, a spin-off movie in 2019 called Dreamland, and a direct sequel initially titled Pontypool Changes (Burgess states the sequel is now called Typo Chan, possibly a play on the fourth through seventh letters of Pontypool and the first four letters of Changes). In 2015, Burgess re-released Pontypool Changes Everything in the anthology novel The Bewdley Mayhem, which consists of The Hellmouths of Bewdley, Pontypool Changes Everything, and Caesarea.

The 2008 film Pontypool was adapted by Burgess from his novel Pontypool Changes Everything, though the film changes everything (well, it changes a lot, but I didn’t want to miss the wordplay). The novel takes a broader view of Ontario, giving us many different characters’ stories. We start with drama teacher Les Reardon, who gets shoved face-first into the impending zombie apocalypse. Les must soon learn to think on his feet, with so many story beats thrown at him it nearly gave me whiplash. After going on the run from Johnny Law, Les embarks on a trip to find his child, and things just get so much more tragic from there. It’s not until Part II of the novel that we are introduced to the film’s feature character Grant Mazzy. The big difference between Grant in the novel Grant and Grant in the film is his occupation. In the novel, Grant is a TV news anchor, while in the film he is a shock jock who was fired from his previous job and gets relocated to the sleepy town of, you guessed it, Pontypool.

Burgess’s prose is nothing short of impressive. He writes like a less pretentious Anthony Burgess (no relation, I think), but with the gusto and academic tone of William S. Burroughs. Whereas those two writers are definitely talented in their own right, Tony Burgess has created a style so raw and precise that it takes him into a league of his own. There really isn’t anything I have ever read that could stand next to Pontypool Changes Everything. To take a step back, let’s talk about the zombies, or conversationalists as he calls them, and what makes them so special.

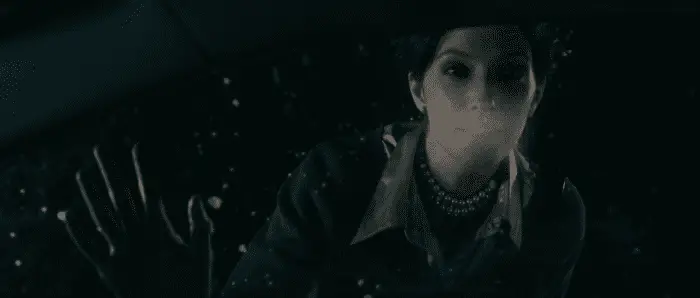

At the core of it all, the virus is spread through language. Yeah! The virus is spread through the English language and through terms of endearment. From there, the infection has a few stages. It starts with déjà vu, with accompanying aphasia; victims are panicked and stunned. Next, depression and physical symptoms start, like your tongue hanging out of your mouth. Then, revenge accompanied by violence. These zombies rip at your skin, but unlike typical zombies, their goal is to end your life by snapping your neck. Throughout this whole ordeal, the zombies repeat words over and over, sometimes repeating what you said perfectly, sometimes twisting your words into strange and incoherent sentences. They call this disease Acquired Metastructural Pediculosis or AMP.

With these unique zombies, Burgess has created something truly interesting—a whole new way of speaking that perfectly fits the world he has thrown us into. While similar to the way Anthony Burgess created a new language in A Clockwork Orange, it’s different enough to be unique and, in my opinion, it’s actually more interesting. At points, Pontypool Changes Everything devolves into nonsensical rambling from the zombies, which does two things. First, it creates a sense of unease in the reader. Second, it forces us into the characters’ shoes and makes us just as confused as they are. We are thrown into this predicament with them, and we have no clue what the F*CK is happening! That is truly why I don’t think I have ever read something this unique or elevated. Did I understand everything? No, but that’s okay. It’s okay to fall in love with a book or a film and not truly understand everything that is going on. The ride that Burgess takes us through in the 276 pages is raw and engaging enough to make the moments that feel like they don’t make sense still fit into the overall narrative.

The film Pontypool, as stated, was adapted from the novel by Burgess himself and directed by Bruce McDonald. The main difference between the two is the setting. While they both take place in and/or around Pontypool, the film takes place in one location: the basement of a church that has been turned into the town’s radio station. Grant Mazzy (Stephen McHattie) was fired from his previous shock jock position and has relocated to the quaint town of Pontypool, a town that relies on the radio to know if the school buses are running or if the schools are even open. It’s clear from the beginning that the narcissistic Grant Mazzy is having difficulty falling in line with the rules of the station, as he constantly butts heads with producer Sydney Briar, who is played by Stephen McHattie’s real-life partner Lisa Houle. The chemistry these two share is so palpable that when the infamous “kill is kiss” scene happens, you’re begging for them to lock lips.

Pontypool is a glorified radio show for the first half of the film. The only way we get information on the horde of people breaking into and dying around Dr. Mendez’s (Hrant Alianak) office is through citizens calling in and from Ken Loney (Rick Roberts), who’s “flying” high above the clouds in his sunshine chopper. The whole story plays out like an Orson Welles radio show. This does what the novel doesn’t: create a claustrophobic setting and force YOU to create the horrors in your head. I think one of the reasons why so many people took a liking to this film, at least the few who saw it, is because it stepped out of the mold of the cookie-cutter blood and guts spewing zombie films of the time that were coming out in droves. Burgess and McDonald made something different and unique that really should have caught more people’s attention. Thankfully, it did receive solid praise when Entertainment Weekly called it “one of the top 25 zombie movies,” and Consequence of Sound ranked it the 42nd scariest movie of all time.

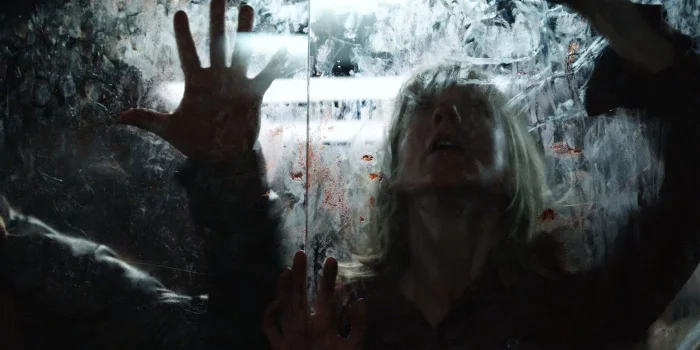

What’s impressive is how Burgess and McDonald earn our time and don’t waste a second of it. Even though the majority of the story is told through the lenses of other people, we do finally get that moment of reprieve when the zombies show up at the radio station. The script does such a fantastic job of hyping up what is going on in the town that it’s almost a sigh of relief when we do finally see the infected people! I saw the film way before I read the novel, but I appreciate where they complement each other, as well as really liking how different they are. They essentially—and effectively—tell the same story but go about it in two completely different ways. To me, that just shows how impressive a writer Burgess is.

This leads me to the final thing for us to look at, and that is the stage/radio play Pontypool. Whereas the ending (post-credit scene) of the film is somewhat optimistic, the ending of the stage/radio play is far more nihilistic than the film, though it paints Mazzy as a more caring and passionate human. Other than that, the stage/radio play is fairly similar to the film.

Finally, Stephen McHattie has got to be one of the greatest character actors of all time. The way he fully embodies the role of Grant Mazzy is second to none. He also has an incredibly sexy radio voice; I would kill to have half the voice he does. In the novel, Mazzy is a caring person who spends his time donating time and money to charities. He’s certainly not narcissistic—he only has one mirror in his house, which he uses for shaving. In the film, he is a narcissistic alcoholic who finally learns some compassion. McHattie absolutely kills his performance; I don’t think anyone else could portray this character. This seems like a role that was specifically designed for McHattie and no one else.

Tony Burgess has created something special here. He wrote a novel, a film, and a stage play about zombies but made it unique and unlike anything that has been made or will probably ever be made. His writing needs to be taught in schools as an example of what can be done with the medium. There is no doubt in my mind that Burgess is one of the great writers of our lifetime, and I can only hope he goes on to write more terrifying stories to keep us up at night.