The horror genre has existed in cinema for over a century—in other words, horror films have been around about as long as motion pictures themselves. From the earliest horror short films directed by Georges Méliès in the 1890s to the faceted, robust production industry that propels the genre today, horror movies have always served us by enabling us to project our forbidden desires and secret fears while formalistically stretching cultural boundaries. Our Horror Through the Decades series examines definitive qualities of the horror genre in each decade from the 1940s through the 2010s.

This week, Rebecca Saunders surveys the sociopolitical context of 1950s horror films.

The past can’t contain them…Rising from the depths of film history to horrify and bemuse…From the lurid period of a genre that died to live again…They’re 1950s horror movies! American and European horror cinema from the dawn of the Atomic Age not only reflects cultural anxiety around nuclear technology and Cold War-era global politics, but it also exhibits the hideous underbelly of repressive social structures in a decade pregnant with social revolution. In addition to their macabre speculation on the transformative atmosphere of the mid-twentieth century, ‘50s horror films were influenced by a metamorphosis of the film industry itself.

In the 1950s, the world—still reeling from the destructive consequences of unprecedented warfare technology during World War II—plunged into the Cold War. The Soviet Union and the United States, along with their respective global allies, engaged in a decades-long geopolitical and ideological bid for dominance. The pivotal aspect of this competition between global powers was the race to develop more powerful nuclear arsenals and to achieve spaceflight. During this period, countries did not engage in world-ending nuclear warfare thanks to mutually assured destruction (MAD), a deterring principle which assured that both sides would be utterly annihilated in the event of an attack.

Constantly, the threat of a nuclear holocaust bombarded the cultural imagination. 1950s horror films’ preoccupations with science, space, and invasions clearly represent collective anxiety about a nuclear attack, foreboding scientific advancement, and subversive agents of ideological opposition. In general, science experiments combined with military intervention are portrayed in ‘50s cinema as both the cause of terrifying problems and also the source of a solution. [1] As a result, this decade reared films that blurred the distinction between horror and science fiction.

In their visions of the atomic apocalypse, B-movies crystallized American paranoia without questioning it. They dehumanized otherness but turned a blind eye to how such dehumanization ended up feeding the nation’s terrors. [2]

One film that exemplifies pervasive anxiety about mishaps in scientific laboratories is The Fly (1958), a sci-fi horror film about a scientist who accidentally becomes morphed with a housefly when testing his “disintegrator-integrator” (a teleportation device). The revelation of his freak accident is framed within a narrative in which people cloak the truth. First, the scientist’s wife conceals what happened, then authorities refuse to believe her and persecute her when she confesses. This framed narrative adds allusions to the shadowy intelligence of espionage to the central representation of distrust in new technology.

If the sheer prevalence of extraterrestrial horror movies during the 1950s is any indication, audiences and filmmakers during this time were also seriously concerned about the new prospect of delving into space travel. Fears of alien life may have been propelled not only by the sociopolitical prevalence of the Space Race but also by the relatively new phenomenon of UFO (unidentified flying object) sightings. Indeed, Project Blue Book—the United States Air Force study of UFO sightings—began in 1952, indicating the prevalence of societal concerns about visitors from outer space during this period.

The most enduring film from the ‘50s about extraterrestrial invasion is Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), directed by Don Siegel and remade several times over in the decades since. In this film, extraterrestrial plant spores reach the earth and then replicate individual humans in every capacity except the ability to emote or to experience individual selfhood. Other prominent extraterrestrial sci-fi horror films include The Thing from Another World (1951), It Came from Outer Space (1953), and The Blob (1958).

If any theme in ‘50s horror films is more common than space invasions, it is mutant monsters. Unlike their precursors, the misunderstood monsters of the 1940s, 1950s monsters weren’t usually your classic monsters, like vampires and werewolves. (Although, these monsters were still present in newer contexts: I Was A Teenage Werewolf, The Curse of Frankenstein, Horror of Dracula.) Typically, monsters of the ‘50s comprised giant beasts that emerged from deep, dark, unknowable recesses of the earth. As the inverse of mysterious extraterrestrial contaminants that swoop down from above, monsters are archaic and unstoppable threats that rise up from below—or within.

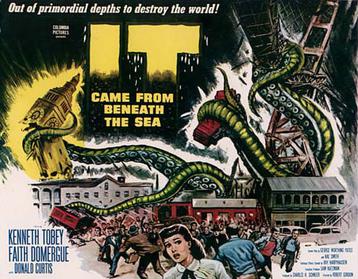

Monsters from the 1950s also often are roused by nothing other than atomic explosions or some other nuclear activity. The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) stars the Rhedosaurus, a fictional dinosaur who is awakened from his frozen sleep by atomic bomb testing in the Arctic. In It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), hydrogen bomb testing in the Pacific forces a giant tentacle monster out from its habitat in the murky ocean depths. These atomic monster films portray collective fear about the unknown consequences of disturbing or destroying vast, uninhabited realms of the natural environment during nuclear testing.

In addition to exemplifying the openly acknowledged fears from this period, the monsters of American 1950s horror films bespeak the domestic and sociopolitical fears of the white men who made them. The pinnacle example of disrupted patriarchal, white supremacist legacy being unintentionally injected into 1950s horror cinema exists in the Creature series: Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), Revenge of the Creature (1955), and The Creature Walks Among Us (1956). Contemporary scholars such as Patrick Gonder and Mallory O’Meara explicate the hidden portents of oppressive social constructs around race and gender as they are embodied in the Creature series.

Leaving aside any major analysis of how ‘50s horror films represent women, the tale of Milicent Patrick serves to illustrate some behind the scenes concepts of women’s agency. An LA Times article on O’Meara’s new book, The Lady from the Black Lagoon: Hollywood Monsters and the Lost Legacy of Milicent Patrick, offers highlights of Patrick’s story. She designed the Gill-Man monster mask in Creature from the Black Lagoon and thus became the first female designer on a monster movie set. Higher-ups in Universal Studios were interested in the talented and attractive lady who helped create Gill-Man. They set up a publicity tour for her which was eventually marketed as “The Lady Who Lives With the Beasts.”

Make-up artist Bud Westmore became so outraged with Patrick’s acclaim over creating the Gill-Man mask that he removed her from the film’s credits and later had her fired from Universal. [3] Westmore received credit for her work for more than 50 years. Patrick’s exploitation and subjugation within her work environment leave us to assume that similar outlooks are embedded in the dominant culture that produced these monsters and these films. This instance of white female exploitation in the production of Creature from the Black Lagoon is amplified by analysis of the women’s role in white supremacist social structures apparent in ‘50s horror.

In a 2004 essay for the University of Colorado publication Genders, Patrick Gonder examines the ideological and social constructs that informed thematic elements of the Creature series as they were produced in the white imagination [4]. In the 1950s, false ideas of racial science and evolutionary biology were grounded in oppressive ideals of racial purity and white supremacy. Throughout the series, the Gill-Man creature represents a caricature of the primitive black man, while the white female who is threatened by yet sympathetic to him symbolizes the white race’s evolutionary potential.

[Creature series films] seem to commit the same racist sin of equating the non-white male with the animalistic and the monstrous, as an imagined threat to white women that justifies the horrific violence of the lynch mob. [5]

Creatures like Gill-Man represent a dehumanizing depiction of Black men in 1950s horror, and Black women’s invisibility in these films is emphasized by a focus on white female bodies. Gonder’s interpretation of the hidden cultural dynamics in Creature from the Black Lagoon corresponds with the perceived threat to white male social control during the 1950s. You have to remember, the 1950s also carried forth the burgeoning Civil Rights movement.

While ‘50s horror films exemplify oppressive patriarchal, white supremacist social structures embedded in the culture that produced them, they are in another sense films created for the culturally marginalized. During this period, in particular, horror was eschewed by proponents of the dominant culture. 1950s sci-fi horror movies were meant for the misfits, queers, freaks, and outsiders, and that alignment qualifies them as at least marginally subversive.

It is no secret that these films are B movies, folks. In the broader context of film history, the 1950s was also an era of decline for the Hollywood studio system, which was decisively put to rest by the Hollywood Antitrust Case of 1948. B movies of 1950s horror were low budget, but they were also remarkably successful. Exhibitors overcame the problem of fewer studio releases through “cultivating the youth audience, financing their own productions, and sensationalizing their advertising.” [6]

Across the board, [1950s horror films] provide a glorious snapshot of the way the USA desperately didn’t want itself to be. [7]

Theaters and new producers broadly implemented special effects and promotions for invasion and monster films, and these marketing devices influenced the horror film genre for decades to come. [8] Promotional gimmicks were deployed in new and shocking ways to attract and engage theater audiences. [9] Studio pressbooks began recommending elaborate showmanship to engage local media and fill seats, and 3D films were featured prominently in theatrical releases for the first time. The success of these tactics was one factor that engendered the mass popularization of 1950s horror films.

One of the masters of these thrilling and creepy promotional gimmicks was American director, producer, screenwriter, and actor William Castle. [10] This guy was really big on the shock factor in audience interaction. For starters, his first major gimmick for Macabre (1958) was to take out a life insurance policy to compensate any audience members that would die of fright. Most of his gimmicks, however, were integrated into the viewing experience. Most notably, for The Tingler (1959) he advertised that the film’s monster would break loose in the theater during the screening. Some theaters even allowed him to install electric buzzers in seats so that moviegoers could tactilely experience the Tingler.

The context of this moment in film industry history shaped the production and distribution of 1950s horror films, and in turn, these changes fundamentally transformed the horror genre. ‘50s horror is also distinctive in that it provides a record of the first cultural responses to global threats such as nuclear warfare and environmental destruction. To understand how the genre functions for contemporary audiences, we may contemplate a hinging question: did 1950s horror sensationalize cultural anxieties to inure audiences to their fears in an outlet for escapist viewing, or did they serve to provoke those fears and instill lingering uncertainty? [11]

References

[1] Newman, Andrew. “The persistence of the radioactive bogeyman.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2017. https://thebulletin.org/2017/10/the-persistence-of-the-radioactive-bogeyman/#

[2] Waldman, Katy. “The Nuclear Monsters That Terrorized the 1950s.” Slate, 2013. https://slate.com/technology/2013/01/nuclear-monster-movies-sci-fi-films-in-the-1950s-were-terrifying-escapism.html

[3] O’Meara, Mallory. The Lady from the Black Lagoon: Hollywood monsters and the lost legacy of Milicent Patrick. Toronto, Ontario: Canada Hanover Square Press, 2019. https://www.malloryomeara.com/

[4] Gonder, Patrick. “Race, Gender and Terror: The Primitive in 1950s Horror Films.” Genders: Presenting Innovative Work, in the Arts, Humanities and Social Theories, No. 40, 2004. https://www.colorado.edu/gendersarchive1998-2013/2004/12/01/race-gender-and-terror-primitive-1950s-horror-films

[5] Gonder.

[6] Heffernan, Kevin. “The Hypnosis Horror Films of the 1950s: Genre Texts and Industrial Context.” Journal of Film and Video, v. 54, 2002. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20688380

[7] Wilson, Karina. “1950s Horror Movies.” Horror Film History. https://horrorfilmhistory.com/wp/1950s-horror/

[8] Heffernan.

[9] Oatman-Stanford, Hunter. “Warning! These 1950s Movie Gimmicks Will Shock You.” Collectors Weekly, 2013. https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/these-1950s-movie-gimmicks-will-shock-you/

[10] Oatman-Stanford.

[11] Waldman.