I recently had the pleasure of interviewing director Jack Sholder. In this interview, we spent 90 minutes discussing Jack’s first three features: Alone in the Dark, A Nightmare on Elm Street 2 and The Hidden at great length. This kind of in-depth look back at Jack’s earliest work made for a fascinating conversation that I hope you enjoy!

AG: I wanted to ask about your first film Alone in the Dark. What was that process like for you to begin work on that film?

JS: I had done a lot of work for New Line Cinema. I met them soon after I moved to New York, and I was hoping that they would distribute one of my shorts, which showed how little I knew about the film business. It turned out that they weren’t interested in shorts, which aren’t exactly a moneymaker. New Line’s whole original approach was film distribution.

This was just when films were really starting to get popular in colleges. For instance, most schools didn’t have a film program. That was new. I mean when I went there wasn’t such a thing. You had NYU, USC, and four or five schools but Film Studies was not something that was really on the map yet. So this all started happening then and anyway I met with Bob Shaye, who said he liked my short film, but he wasn’t going to distribute it at this point, but by the way, did I know anybody who would edit a trailer? I had been working as an editor for about three months. I’d also made two films on my own in college, and I had edited those. So, I said, “Yeah, I can do it,” and he said OK, which was kind of nice.

It used to be pretty expensive to edit a movie because there was all this expensive equipment that you needed. You couldn’t just turn on your laptop and away you went. Bob rented somebody’s cutting room for the weekend, basically starting when they left for the weekend and we came in and basically locked ourselves in a room and emerged like 5 o’clock Monday morning with a trailer, and we ended up becoming friends.

After that, I did all of their trailers whenever they needed a trailer or Bob always thought every movie was 15 minutes too long, so he’d hire me to come in and take 15 minutes off. I would do that off and on, in between the other editing work that I was doing. It was a nice arrangement and kept me going during times when things were not as wonderful as I might have hoped. Flash forward to 1980, and I was sitting around with Bob and some of the people from the company. I think a joint was being passed around and probably some vodka and one of the guys said, ‘you know the distribution business is getting really hard.’ There was a lot of competition from the majors. This was after Halloween and Friday the 13th, and all these really low-budget movies were making a lot of money. He said, ‘you know if we could make a low budget horror film, we really know this market, and we can make a lot of money.’ I went home and I thought about it a little bit. I came up with an idea, which was basically a group of criminal psychopaths are locked up in a hospital with an eccentric head of the hospital and everything is on electronic security.

There’s a blackout. There had been a big blackout in New York a few years earlier. I mean there was no power whatsoever in New York for like three days. So I got this idea that there’d be a blackout, all the electronic security would go out, and the criminal psychopaths would waltz out. They would basically terrorize Little Italy, and eventually, the Mafia would decide to round them up and put them back. They liked the idea and told me we’ll pay you so much to write it—not a lot. If we raise the money and actually make the film, we’ll pay you—not a lot—to direct it.

I wrote the film, and they were unable to raise the money. I actually went off and cut the film called The Burning, which is the first film that the Weinstein brothers did. I learned a lot about how horror films work. I had never been a huge fan of the genre. I really learned about how you build suspense, and you build scares and stuff like that. I went back and I rewrote the script, and I’m not sure it was because I rewrote the script or whether it just was just a little bit better, but they raised the money and we made the film, and the rest is history.

AG: Looking at that film today, the cast alone is pretty considerable for a small budget film. It’s definitely a film that’s grown in popularity throughout the years. What’s that like for you to see something that you created at the beginning of your career escalating in popularity throughout the years?

JS: Well I’m really pleased because the film didn’t do a whole lot of business and it sort of got beat up by the critics. Some people appreciated it. It just didn’t do that much. I wasn’t quite sure where I was going to go from there. Was I going to be just a one-shot wonder? But I always thought it was a good film. When I watched it again, I mean I probably hadn’t seen it in 20 years, I said you know this is a really good film. I never set out to be a horror filmmaker. A guy like Wes Craven, he really expressed himself through the genre. I sort of tried to express myself in spite of the genre. What I was trying to do was to make an art film, and it’s pretty quirky. It has a really existential ending to it. People called it a slasher film, but I wouldn’t classify it as a slasher. Whatever it is, it’s masquerading as a horror film, but it’s really my way of sneaking in an art film.

AG: It has a cool place in cinema history too, being there towards the beginning of New Line and then looking at the talent that was in that film and the careers those guys were going to have as well.

JS: Yeah, or had already had. I just kind of lucked out. I mean we got these guys when they were sort of at a low point in their careers. You know it’s not like they were all like, ‘We’ve heard about this great kind of artsy horror type film, and we all want to be in it.’ It’s just like they need a paycheck.

I remember the producer asking me what I would think about having Jack Palance in the film. ‘Wow, that would that would be great’ I remember saying. I mean he was one of the great screen villains. So he was able to get him. Then he said he thought we could get Donald Pleasence. I was a huge fan of Donald Pleasance. I thought and still believe that he’s one of the great actors. I was thrilled to be able to get these guys. Martin Landau, his agent, actually called us to solicit a job. The guy had to work, and we benefited from that.

Later on, Palance, before the film actually went into production, got an offer to be in a TV series and he tried to back out. New Line threatened to sue him. So instead of going to Florence to shoot a very easy TV series—I think it was Ripley’s Believe It Or Not, where he was basically going to introduce the shows, he had to go to New Jersey for a low-budget horror film. The budget was a million dollars, but Bob was freaked out about spending all that money. Also, they had told Palance that there would be no night shooting, for a film called Alone in the Dark. Somehow he didn’t put two and two together there. I think on the second or third day, he had a 4:30-afternoon call. It was the scene in the disco that was just a complete fiasco to shoot, and he got called to do his first shot at I think five o’clock in the morning, so he wasn’t pleased. I actually have a signed photograph of him and me, and he wrote ‘It wasn’t fun, but it was funny.’ I mean he was a great guy. I learned a huge amount by working with him. In an odd kind of way, he would teach me things. Not explicitly but he would just do things to sort of make a point. I learned some really great lessons from working with him. Just to work with people of that caliber is fantastic.

AG: Your second film was A Nightmare on Elm Street Part 2. What was that like for you when you were offered the sequel to a hit film?

JS: Well, my first reaction was ‘No,’ which kind of surprises me. I never thought of myself as a horror film filmmaker. I felt that it was a means to an end and at that time, 1981, 1982, sequels were sort of a rip off the original to make a little more money. It’s not like now where you expect the sequel is going to do better than the original. It was a kind of a less than thing. Honestly, I never thought Elm Street was that well-directed movie, so I was not intimidated by the challenge of having to follow in the footsteps of a masterpiece.

A friend of mine in the business said listen; this film is going to make a lot of money because the first film made a lot of money and then you’ll have a career. Make the film. You know you can do a good job on it. I was persuaded, and he was absolutely correct. When the movie opened up, it didn’t even have a national opening, which most films didn’t at the time. I think that we were the top-grossing film in all the markets and New Line was expecting that the film would do at least 70 percent of what the original made and it ended up making more than the original. Monday morning I get a call from the head of my agency, who I had never spoken to before and he’s telling me that Dino de Laurentiis is just going to call you from his car in five minutes. At that point to have a phone in your car was a really big deal and to get a call from Dino de Laurentiis was a huge deal. I realized that my life has just changed.

AG: Nightmare 2 was known for flipping a genre staple so to speak and having a male lead. Were you involved at all in the scripting process at all?

JS: Not at all. Wes (Craven) was initially supposed to direct the sequel, but he never liked the script. They thought so much of the sequel that they hired David Chaskin, who worked in the New Line office to write the script. It wasn’t like it was all Wes’ idea, and now Wes was now going to take this saga to the next level, like going from Godfather 1 to Godfather 2. I think Wes just sort of figured he could make a little bit more money and then I think he had other opportunities. He never liked the script because, for one thing, he felt it violated the central concept of Elm Street, which is that Freddy only appears when you’re asleep. In that movie, he appears in the pool party when everybody’s awake. So about six weeks before they were going to start to shoot the film, he backed out. I had always been sort of part of Bob Shaye’s brain trust if you will. Bob always liked to get other people’s opinions, and then he would do what he wanted. He had realized that he didn’t always make good choices, which is pretty much true for everybody.

I had read an early draft of the original, and he asked me to give some notes. I had actually visited the set once when it was being shot and I helped out a little bit in editing. I didn’t really edit it, but I helped him get it ready for screening. I was just like another pair of hands. I knew the film quite well, and Bob trusted me. I got hired six weeks before the film started shooting and they were already in pre-production. They already had hired a production staff and some of the people. The train was already moving down the track. It wasn’t speeding down the track, but it was already moving down the tracks, and I had to jump into that and it was frankly terrifying. You know I usually have input into the script, but I had very little time to really do any of that. We probably made a few changes, but I didn’t really have a whole lot of leisure to sit down and work on the script. They were pretty happy with the script, so I just sort of took it as well, here’s what I have to do. I have to shoot the script in the best way possible.

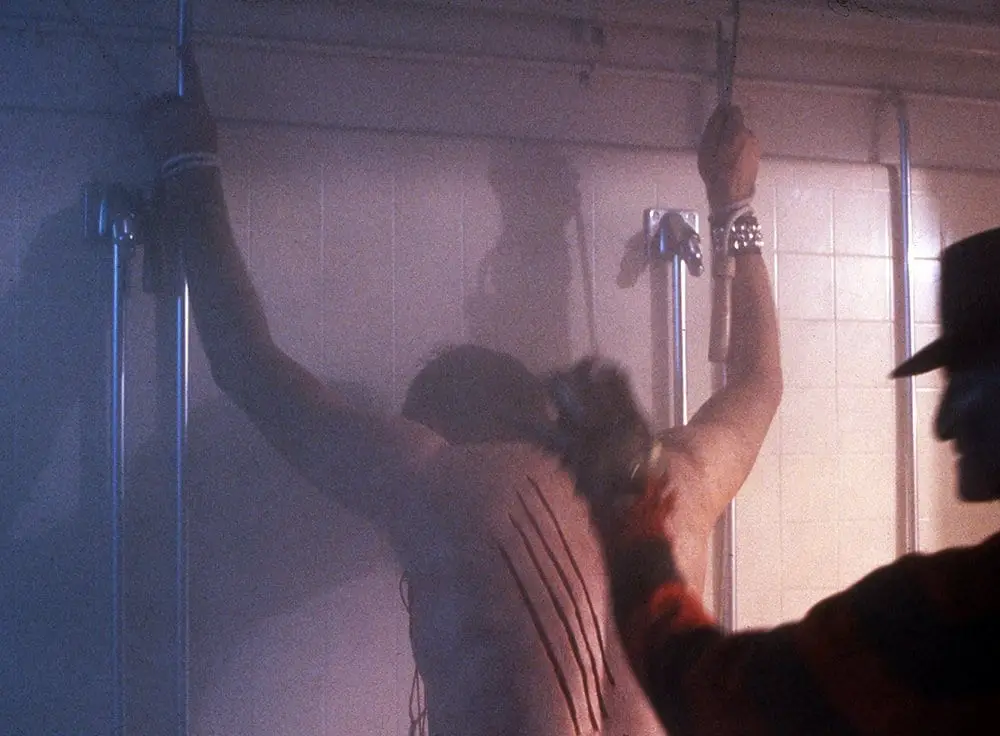

Also, there were no rules. Look at the original poster for the film, which I’m staring at right now. There’s no Freddy in the poster. Look at the DVD now Freddy is all over it, but there’s no Freddy on the poster. They didn’t even know what he was all about. They didn’t even want to bring him back really. I mean they wanted to bring him back, but his agent had the nerve to ask for more money they felt that these guys are trying to hold us up. How dare they do that? There was this whole debate, and it was almost like an ego thing, we’re not going to give in to their demands. We can get anybody to play Freddy! How many different people played. Michael Myers or Jason? The thing that I thought was great about the original was firstly the concept was terrific and then to cast somebody like Robert Englund. You look at Robert Englund; he’s got a funny-looking face. He’s not a big menacing guy. He’s a superb character, and that’s part of what made it work so well because they created a character and then cast somebody who could take on that character really well. We never had a casting session for another Freddy, and I think it was always assumed we’d get around to getting Robert back. Probably two or three weeks before we’re ready to shoot, they said okay we made a deal with him, but he’s not available the first week. We ended up doing this scene in the shower where he doesn’t have any lines with an extra who walked out of the shower. He was awful. I would have to say ‘Stop walking like a monster, you know start lumbering to war, walk with authority.’ I got Robert back finally in the second week, and he just had this presence, there was a power there that he brought to the role.

I was basically just trying to get through it in one piece. I was in a state of real anxiety, if not panic. Anxiety with occasional moments of panic as we were prepping the film. The first day they handed me a list of like eight single-spaced pages of all these effects in the film and I had no idea how to do any of them. It was terrifying. How are we going to do this? I had no idea. Of course, they hired someone who was supposed to know how to do all of that stuff. They never put any pressure on me because their expectation was low. They weren’t expecting to have a huge success. They were expecting you know, to make a decent profit. They weren’t expecting to launch a billion-dollar franchise.

The only request or demand, however you want to look at it, was to keep Freddy dark. They didn’t like the makeup for the first film. I hired Kevin Yagher. I really liked his work because he was actually a fine arts student rather than a kid who read Fangoria from the time he was six years old. He was a sculptor. I liked the fact that he had an artistic background. All they knew was, Freddy’s scary, so let’s make sure that we keep him scary. Let’s keep him dark. We never wanted to have his face fully revealed and the Director of Photography, Jacques Haitkin was the guy who had shot the original and so he had been hired to shoot the second one, which was fine by me because I had known his work and I thought he was terrific. I was delighted to work with him because A) he was good and B) he knew how to do the film, so that took a certain amount of weight off of me.

AG: You said there was no expectation that a series would launch from these two films.

JS: Let me re-phrase that. No one had any idea that it was going to become what it became, but there was hope that they’d be able to do a third one. In the first film, I think they shot two or three different endings. The ending that’s at the end of the first one was not the original ending, but New Lines felt that they needed to have an ending that would open it up to the possibility of a sequel. The same thing happened with ours, which was that they wanted to have an ending that would open up the possibility that Freddy wasn’t really dead.

AG: How do you look back on your experience making this film?

JS: I was filled with a lot of anxiety and fear while I was prepping the movie. I was really in a state of stress the entire time. I felt like I had to climb Mount Everest. I had all these huge numbers of effects, and it was extremely intimidating my mind. I kind of have a disorganized mind. My way to compensate was to prep fanatically, which I’ve always done. I have always planned out every shot of the film, for every film I have ever done before I ever shot it. Which isn’t to say that it didn’t change when I started to shoot it but I literally I had shot lists for every single scene of every film that I’ve ever done before I began to shoot. For me, it’s like “OK, this is what I have to do here.” It basically forces you to think through the scene in a very careful way. First, I have to say, what is this scene about? Okay, now how do I want to stage that scene? Do I want to shoot the scene in a bunch of quick cuts or one long dolly shot? Do I want to shoot it in a really interesting way or do I want to shoot it in a way that doesn’t distract from what the actors are doing? By the time I’ve done that, I kind of feel like I’ve already kind of made this film in my head. I feel like I can walk on and somebody can ask ‘what do we do now?’ and I can look at the piece of paper say ‘Okay put the camera there’ and so on. I did an enormous amount of prep and the interesting thing was on Day 1 of the shoot, my nerves had completely gone away.

I didn’t feel like it was a very personal film, although there were certain aspects of the film that would definitely fit into my worldview. Watching my films after not seeing them for a while, I think a lot of my movies are social commentary. Alone in the Dark, definitely. What’s really crazy and what isn’t? How thin is that veneer of civilization when something happens that is as simple as all the lights go out? People sort of revert. The Hidden, very much so. There’s also you know that element in Elm Street that for me was about adolescent sexuality, how do you deal with it? When I thought about horror films, I said what really scares me in a fundamental way? What is this sort of thing that just kind of fills me with dread? If you’re a teen, sexuality could be the boogeyman. What is it? Am I going to be okay? My agent told me a story that when he was like 14 or 15, he had a physical and the doctor did a rectal exam and he got on and got a hard-on he said ‘Oh my God I’m gay.’ He was freaked out for like weeks, and that’s the kind of thing the film was about.

AG: Horror as a genre is starting to evolve more over the past few years but wasn’t always known for social commentary, which makes films like A Nightmare on Elm Street 2 stand out even more.

JS: I did an event with Mark Patton a couple of months ago, and I hadn’t seen Mark much since we screened the movie. I cast him, he was my first choice, and New Line went along with it. They all felt that he was perfect for the role. He and I were director and actor; we weren’t really buddies. He always seemed a little out of sorts, and I always thought well maybe it’s just, you know because the character is going through all this stuff. I met him at an event about four years ago and learned his whole story, which I’m sure you know—that he was a closeted gay man, and that he dropped out of the film after that. His experience of the film was completely different from my experience. For him, it was this incredible psychodrama that had to do with his own identity and his own fears. He had spent his whole life with the idea that he could become a movie star. Here he was starring in a movie and people were telling him that he was a gay character. He’s been trying to keep that under wraps and it just you know completely freaked him out. I had no idea that was going on—I had no idea he was gay. I didn’t think about whether he was gay or was he not gay. It just wasn’t a question.

If I had cast somebody who was like the Robert Rusler character, the movie wouldn’t work. You needed someone who had that very vulnerable side to him, which is what Mark had more than anybody else that I had seen for the role. I felt both intellectually, and I think intuitively, that the vulnerability was what the role required for it to work. As you said, it kind of switches the norm. That meant that he’s in the girl’s role, that he’s the victim who’s weak. I was doing a job, but of course, when you do a film, you have to find a way into it, and you find a way to think it’s like the greatest thing there is while you’re doing it. Otherwise, it’s tough to do. I thought that we were making a good film. I was happy with the way it turned out.

Most people want to ask about the ‘gay controversy’ with the film. Anytime there’s any screenings or anything; it always comes up. According to Mark Patton, it’s now studied in universities and it’s in collections and so forth because of that. I mean he sees things through that lens. That’s kind of the rap that it’s gotten over the years, the gay element people think the film has. For the record, none of us at New Line ever considered that. There’s a question of whether David Chaskin did. Mark has made a lot about his role and whether he knew that the film had this strong gay subtext.

As I said, I always look for what is the spine or the subtext of the film, whatever you want to call it. Citizen Kane is about the loss of innocence. That’s what Rosebud is. That’s what Orson Welles was directing. That’s the story of every character in that film. That’s the story of the film. So, it’s like what’s the Rosebud of other films? I’ve always tried to figure that out because I felt that once you have that, it gives you something that unifies everything, and that gives coherence to the movie. I think most good directors have that. For instance, with The Hidden, it struck me that what it was about was what it means to be human. For Elm Street, it was about teen sexual anxiety and one aspect of which is the fear of homosexuality.

AG: Were there any discussions about you returning for the next film or any of the other sequels?

JS: No. I think that they knew that I would have said no. The film had opened up a lot of doors for me, and I didn’t want to do a sequel to a sequel. I didn’t really want to do another horror film and get typecast, which is exactly what happened.

AG: Your next film was The Hidden. What was your experience like making that film?

JS: After Elm Street, I moved out to Hollywood. I was definitely on people’s lists. I wasn’t on the A-list, but I was on the B-list so I got offered a lot of stuff and most of it was very easy to turn down because it wasn’t very good. I was waiting to get a really good script because you can’t make a good movie if you don’t have a good script. I have been cursed with good taste. If I read something that’s not good, I just can’t take it seriously.

Finally, a fair amount of time had passed and the heat was starting to cool down. Sara Risher, the Head of Production said we’ve got the script and I think it might be a really good script for you. She gave me the script for The Hidden, and I read the script it was like OK I’ve got to make this movie. I love this script. I gotta make this movie. They already had another director attached at that point. I don’t know how attached he was, but I came in and said I really want to do this film.

I met with the producers, and I had a real passion, and I had a real take on what the film was all about and how to make it. Everybody said, yes we should let Jack make the movie. That was one where I just knew it was going to be a great movie. It was such a good script. The script was written by Jim Kouf who wanted to direct it and he had taken it around all over Hollywood, and nobody wanted to make it. He took it to New Line and they said well we’ll make the film, but we don’t want you to direct it. He pretty much said fine I’ll just sell you the script and I don’t want to have anything to do with it. I’m going to take a pseudonym as the writer, which of course now he’s since gone back to putting his real name on the film. I had some changes that I felt the script needed. I felt that there were certain areas of the script that were weak, and I did the rewrites myself since Jim basically had bowed out.

AG: In this film, you worked with a younger Kyle MacLachlan who was at the beginning of his career. He had a few films under his belt at this point, such as Blue Velvet.

JS: He hadn’t done Twin Peaks yet though. Yeah, he was young. We didn’t cast the film until literally three or four days before we’re going to start shooting. A lot of movies, they’re really cast-dependent. A lot of films that I’ve worked on, it’s like well we won’t greenlight the film until we get a cast that we’re happy with. Then you offer it to Robert DeNiro, and then you wait two weeks for him to read the script and turn it down. Then to Al Pacino and then he waits three weeks for him to read the script and turn it down. It’s horrible; it’s torture. With The Hidden, there was a start date, and they were making the film. We just had to get a cast to be in the movie.

I had seen Michael Nouri early on, and kind of didn’t take him seriously. You know this guy’s Michael Nouri, are you kidding? He’s totally the one for the part. We were a week away from shooting and we didn’t have anybody for the Kyle role. We said to the casting director, bring in everybody that you can find who will come in to read for this. Kyle was one of those people. He came in sort of in the middle of the week, and I thought he was terrific. Then we brought him back. The only other contender was Peter Gallagher. Peter was good, but I just thought Kyle had something extraordinary going on and I had to really talk New Line into it because they said, ‘Well Kyle he’s just kind of like weak. He seems like he’s a weak guy. He doesn’t look very strong.’ I said that’s the beauty of his character. You have a guy who looks like he can’t do this, but then he actually does it, so you’re rooting for him. It was interesting because when we were making the movie, I knew he was good. I knew he was actually wonderful, but I was worried that he was disappearing because Nouri’s character was much more effusive and he had a lot more lines of all of that. Now I see it totally as Kyle’s movie. He had this quiet strength, and he was such an interesting character.

AG: Any parting words for those reading?

JS: I fell in love with film. I’ve watched films that I love, and I would just walk out of the theater and feel different from when I walked in. That was always what I wanted; I wanted to do that. I wanted to make a film that would make people feel something new and make them feel different—make them walk out of the theater feeling good or elevated or sad or something. That’s what I did it for. All the other things that come with it are great, but really that was and is my main attraction, which is to see if I can turn people on to things that turn me on.

If you enjoyed this interview, please be sure to check out some of our others!

The Sound Of Fear: A Conversation With Writer-Director Graham Reznick

Daniel Farrands Discusses Next 3 Films, Writing Halloween 6, Horror Documentaries & More!

Rebekah Del Rio discusses meeting David Lynch, Mulholland Drive, No Stars, and more!

3 Comments

Leave a Reply