Frost-coated Chicago is an odd season to explore the paranormal on Prairie Avenue. On the one hand, winter lends a picturesque quality, uniquely enticing. With the average temperature almost guaranteeing frostbite, the street is often eerily empty. Consequently, that same cold makes a walking tour thoroughly impractical. Yet, despite parts of me still thawing, I endured the freeze to collect the curious tales of this haunted area.

The historic district, once known as Millionaire’s Row, is located on the Near Southside. It begins where 18th Street slips into a curve arching down narrow, tree-lined Prairie Avenue. Once there, it’s easy to get caught up in atmospheric insinuations. Streetlamps cast a tinted glow vaguely reminiscent of gold, while lights broken by branches spread shadows alongside a sprinkling of cinematic horror seasoning. It’s an ideal setting for the “numerous stories of untimely endings, and even today, stories of unexplained sightings and sounds.”

Prairie Ave. is a tucked-away stretch. Hardly hidden, it’s still easily ignored. The kind of street a motorist can pass a dozen times before ever really acknowledging it. There’s no reason to go down Prairie unless one lives there or is dropping off a delivery, especially since it isn’t a through street. A concrete oasis breaks the avenue in the middle, rendering it a primarily pedestrian thoroughfare.

So it is, one will typically be on foot when taking the road. The surrounding antiquated structures glower at passers-by. Every other building is reminiscent of The Exorcist poster, and despite being in the city, it all feels isolated.

I joined a tour presented by American Ghost Walks at the corner of 18th and Prairie. There stood the imposing edifice of the John J. Glessner House, the building’s exterior implying a prison more than a luxury mansion. What follows is based mostly on the tour guide’s claims of paranormal activity. Here and there, however, I’ve endeavored to add other relevant source material as well as my impression of places.

Built-in 1886, the property housed the family of John Jacob Glessner, who made his fortune selling farm equipment. He hired Henry Hobson Richardson to design the building. Utilizing a style that would become known as Richardsonian Romanesque, the architect fashioned what seems, as I said, more prison than a palace, at least until one ventures inside.

The uninviting exterior houses a surprisingly cozy interior. What the other elite residents considered an eyesore provided the Glessner family with an impressive amount of privacy. The brick bulwark outside shelters a delightful courtyard within which there is copious natural lighting during the day. Even at night, the place remains remarkably charming. It’s no wonder paranormal reports here are typically amiable.

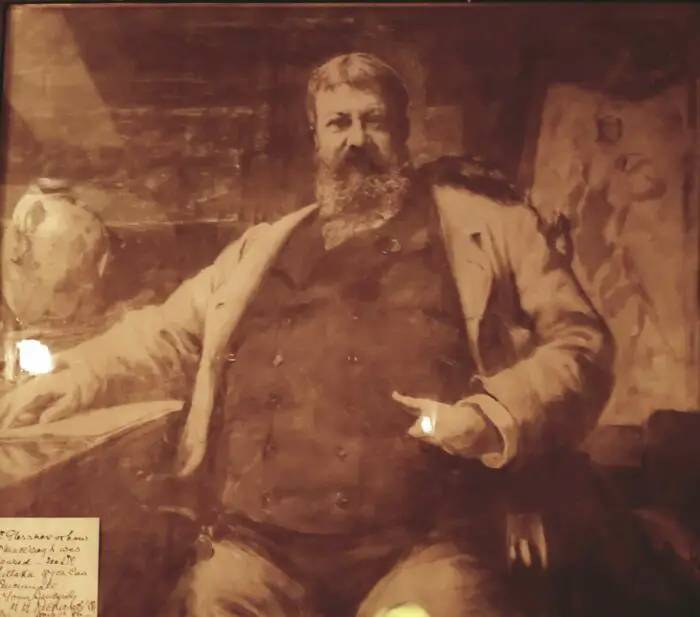

People claim to have felt a pleasant presence; cold fills an otherwise warm room, then the mood lightens due to some imperceptible influence. It’s believed the ghost of H. H. Richardson haunts the premises. The architect died before construction was completed, but the Glessner family was so impressed with his work, they commissioned a portrait of him that is hung in a main part of the house to this day. According to the tour, Richardson was a jovial fellow who enjoyed life to the fullest, so it’s no surprise people associate his ghost with a friendly atmosphere. He’s that uncommon specter who doesn’t inspire fear.

This makes the Glessner house an interesting place to begin a paranormal tour. Once inside, any eeriness about the mansion melts away. More fascinating from a historical perspective, claims of the supernatural almost feel like a side dish. The real entrée is the architectural achievement as well as the delightfully cozy wood-paneled interior. The rooms are hardly ominous, so the spooks here are inconceivable as mournful specters howling in grief. Which, by all accounts, H. H. Richardson is not. Rather, it’s the simple fact one feels so at home, if possible, it’d be best to never leave. Whatever specter lingers in the Glessner House, perhaps they just can’t imagine being anywhere better.

This made the rest of the tour something of a sharp turn. When venturing back out into the cold, there’s a real sense of leaving the light behind. Now returned to a world shrouded in shadow and frost, we turned our attention to the other paranormal places on Prairie Ave.

First, the Kimball House across the street. There lived William Wallace Kimball, founder of Kimball International. Originally from Boston, he started a piano-selling business with only four instruments to sell, eventually becoming a manufacturer of organs and pianos. He married Evalyne M. Cove in 1865, and it’s she who still haunts their châteauesque home.

Designed by Solon S. Beman, the property is in accord with a revival of French architectural styles. Employing asymmetrical elements along with spires, receding planes, and a broken roof-line, such structures emulate French Renaissance châteaux from the Loire Valley. These elements are easily seen in the Kimball House. It’s almost a small castle covered in windows, hints of a Gothic influence giving it a touch of the sinister at night.

Evalyne Kimball used to throw lavish parties to show off her enormous collection of paintings by Old Masters. This term typically applied to accomplished European artists who were active before 1800 (though there is some flexibility on the timing)—Botticelli, Raphael, Goya, Hieronymous Bosch, William Blake, etc. Imagine a Gilded Age barbeque where the yard decorations are Renaissance paintings or an evening of cocktails surrounded by Baroque masters.

Towards the end of her life, Evalyne Kimball began to suffer from dementia. As such, she continued to show off her collection, entertaining empty rooms she thought were full of visitors. Her ghost is sometimes seen peering out of the front windows, eying the street to see if anyone is coming, waiting for someone to share her art with once again. The shutters in the Kimball House have been seen shaking at times when the air is still, and no wind could rattle the window. Even the glass occasionally shakes, or so the stories go.

Leaving the lonely, mad ghost behind, we went up the street to the next house. Built by Elbridge Gerry Keith in 1870-1871, the mansion is one of the seven to survive the decline of Millionaire’s Row. On this “sunny street that held the sifted few,” many of the original structures fell into disrepair and then ruin. Being near the Chicago River’s south branch made it an ideal area for blossoming industrial enterprises, affording handy proximity to businesses in the South Loop, lumberyards, and railroads. Wealthy white residents fled the growing noise and pollution as well as the increasing presence of immigrants and African Americans. In an early display of what became known as ‘white flight’, they abandoned the avenue for other neighborhoods more appealing to the affluent. Many of the mansions didn’t survive the years that followed. But the Keith House still stands.

This is the building ghost hunters come to witness. Designed by John W. Roberts, the Keith House features French motifs combined with Neo-classical elements. The result is a Victorian châteauesque structure that resembles a classic haunted house. It’s easy to envision Scooby and the gang racing out in fright, or a Stephen King novel opening with a description of the property.

Elbridge Keith lived on Prairie Ave. with three of his brothers. After working as a clerk in a general store, he joined his siblings Edson and Osborne in Chicago. From a humble beginning selling hats, the Keith brothers eventually built the largest millinery company in the United States. Unfortunately, success did not mean peace of mind. One of the brothers, suffering from migraines and insomnia, walked into nearby Lake Michigan and drowned himself.

The Keith House now stands empty on Prairie Ave. The various tragedies of the past, from suicide to abandonment, have left an air about the place that could easily be called haunting. The residence almost seems aware of having been left to decay, yet still stands with a stoic bitterness. Claims insinuate something alive dwells within and ghost cars from a bygone era have been seen coming out of the narrow driveway. If nothing else, aesthetically speaking, the Keith House is the most conventionally supernatural structure.

Finally, we strolled to the residence of Marshall Field Jr. This is easily the biggest house on Prairie Ave. Words like ‘palatial’ were created to describe such places. Built by his father Marshall Field as a wedding present, its luxury knows no bounds. The Fields family, Marshall Senior especially, are well-known in Chicago. The department stores he started made him a vast fortune in no small part due to their emphasis on service and quality. His business associate Henry Selfridge encouraged the use of the slogan ‘the customer is always right’, and it’s telling how long someone’s inhabited Chicago by whether they call the location of the old store Marshall Field’s or Macy’s (the latter having bought the premises in 2006).

Another property designed by architect Solon S. Beman, the home of Marshall Field Jr. is imposing in a different way from the Glessner House. The implication of wealth necessary to casually construct such an estate is staggering. It immediately calls royalty to mind. As such, while the Glessner House may have a deceptively uninviting exterior, the home of Marshall Field Jr. casts an invisible velvet rope barring anyone below a certain income bracket from even thinking of coming inside. Still, all that wealth didn’t save the 38-year-old from a bullet.

His death is an odd story, to say the least. Though Jr. died of a gunshot wound, how exactly he received the injury is open to speculation. The Fields family insisted he shot himself by accident while cleaning a firearm in preparation for a hunting trip. However, that doesn’t fit with the bullet hitting him through the side. Furthermore, if the injury was so innocuous then it’s even more intriguing given Marshall Field’s insinuation he would stop advertising in any newspaper which published an account contradictory to his own. In other words, when rumors from a local brothel began circulating that Jr. had been shot there, papers hesitated to risk their lucrative ad revenue reporting the allegation.

Now, the proprietors of that bawdy house, Ada and Minna Everleigh—Chicago legends in their own right—insisted the claim was meant to discredit the reputation of their establishment, the Everleigh Club. However, it was an ill-kept secret that Marshall Field Jr. frequented the place. So did many other men living on Prairie Ave., given the Everleigh Club stood a horse trot away on Dearborn Street. Whatever the case, the salacious nature of the story has kept speculation alive ever since Junior expired in Mercy Hospital.

This bit of true crime doesn’t seem to have conjured much of a paranormal aftermath. That said, our tour guide giddily alleged that when new owners took over the residence, they had an exorcism performed to expel an ethereal miasma from the place. In essence, the home of Marshall Field Junior is haunted in a manner, not unlike the Glessner House, only the ghost here is far less affable. This spirit sours the air around it, leaving those exposed to its presence in a darkened mood.

As I mentioned earlier, the Glessner House seemed an odd place to start our paranormal perambulations. Yet in retrospect, it may’ve been subtly setting up expectations. The tour there provided few supernatural stories, and whatever ghost tales existed took a backseat to architecture as well as plain human history. The rest of the tour functioned in much the same manner, becoming more of an architectural exploration spiced with a little true crime alongside one or two supposed supernatural sightings.

Still, the paranormal bookends of the Glessner House against that of Marshall Field Jr. are intriguing. All the purported ghosts on Prairie Avenue are like that. These aren’t specters floating down stairways or whose howling shatters silent nights. They’re presences, some seemingly lonely, peering from windows and idly strolling the sidewalks.

Our tour guide showed a photo of a face, a supposed specter looming in a window in the vacant Keith House. I found Our Lady of the Underpass a more convincing supernatural image. The frosted smudge on the glass he offered as proof of the paranormal hardly resembled a face let alone a reason to believe in ghosts. Yet, when I went back to walk the route alone, I couldn’t help understanding why someone would look at the Keith House and start to believe something paranormal lurked in those darkened windows.

With that in mind, I still felt it necessary to dismiss the insinuations of specters produced by the Fort Dearborn Massacre. Though people claim to have seen ghosts from the War of 1812 wandering around the area, colonials as well as Potawatomi, the massacre did not occur in this part of Chicago. There’s sufficient historical evidence to deny such a claim, so I feel it would be misleading to share any supposed ghost sightings related to it.

Pointing out the architecture may seem pointless in a paranormal piece. However, those elements give each of the houses personality. Even when similar due to stylistic inspiration, the homes on Prairie Ave. have a uniqueness that makes each easily distinguishable. They have, in a way, faces that belong to a lost era. Though more modern properties have endeavored to recapture the old aesthetic, their mimicry only accentuates the vanished past.

Prairie Avenue of the Gilded Age, in essence, died, and the only corpses left are the houses standing in mute testament. They confess that no amount of money can stop the march of time, the decay it brings to all things, and that eventually, all that remains are memories and ghosts. At least in the Glessner House, there’s a sense those can still be pleasant.