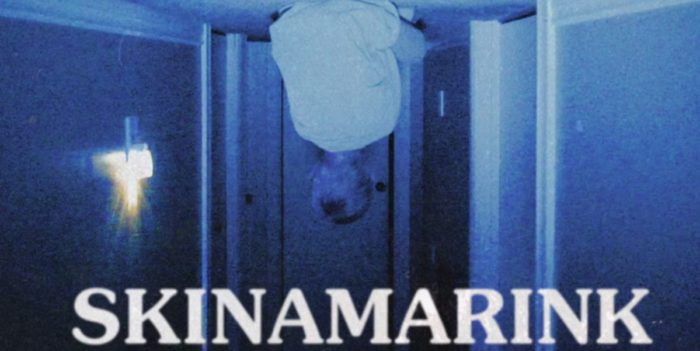

The title Skinamarink is sure to hit on the nostalgia of the subconscious minds of older millennials and younger Gen-Xers. Typically followed by “a-dinky-dink, skinamarinky-doo,” the song from Sharon, Lois & Bram’s Elephant Show is often met with a delightful remembrance of old children’s programs, further followed by conversations concerning the love for Fraggle Rock, Eureka’s Castle, and other shows of the similar era. However, tell people about Kyle Edward Ball’s latest film, about two young children awake in a nightmarish dreamscape of light vs. dark, then the made-up word Skinamarink becomes familiarly haunting. I was drawn to Ball’s film the second I read the title on the Fantasia press release. That feverish duality of a once friendly association, usually met with delight, poised to terrorize with the artful context of horror infringement. Skinamarink, as a name in this context, intimidates and threatens.

Described as an experimental film, Ball’s movie isn’t nearly as experimental as some other films I’ve seen bearing that descriptor. It provides a clear narrative, but it’s filmed more like a piece of high art. The movie is about two children, Kevin (Lucas Paul) and Kaylee (Dali Rose Tetreault), who wake up in the middle of the night and find their parents are nowhere to be found and specific features of the house, like its doors and windows, have been removed. The kids decide to wait for the grownups to return, only to discover something in this version of their house is hiding in the darkness and slowly removing the light as it calls for them to play with it.

Skinamarink is a dreamlike feature calling to mind the short films of David Lynch while utilizing the aesthetic of a Super 8 camera, though undoubtedly shot in a wide frame. Most of the time, characters appear out of focus or out of the frame entirely, as the movie makes the dark spaces its antagonist and the retreating light of the film its underdog protagonist. Toys and the warm glow of the tv become supporting characters as our main characters are only ever seen as an appendage, shadows, or silhouettes.

Playing on those childhood fears of waking up late at night to a dark and silent house, devoid of the boisterous activities and family bustle, the viewer embarks on their own journey of the fearful qualities of a well-known place late at night. Ball uses varying degrees of darkness, complemented by the grain of the film, to prey on his audience’s nyctophobia (fear of the dark). The pixels move, shake, and swirl, catching the viewer off guard as their eye attempts to trace and find anything stumbling around in the darkness. It’s likely all hallucinatory, just a mind playing tricks, as there probably isn’t anything there. Similar to the hypnogogic state we feel later as adults when we sense something in the shadows as we begin to doze off.

I typically dread when films use older technology to build an aesthetic but applaud Ball for using modern technology to fit the look instead. I like the look of Skinamarink. Set in 1995, it feels twenty to thirty years older than that. This look works, and Ball fills the screen instead of feeling the need to contain it in a 4:3 frame. I get why some do it (see: The Lighthouse, You Won’t Be Alone), but honestly, I’ve rarely found it an immersive experience. Skinamarink is all for having older technology inside the film, CRT television sets, and corded telephones to take us back to that era. Luckily, Ball is an artist that believes in immersion—advantageously employing the widescreen element, granting him more places to play in and fill with the ominous and foreboding nature of the dark, negative space. This is how the film unsettles, gets under your skin, and scares the sh*t out of you.

Mainly seeing a cascade of images, like those we might remember if we think back to the early mornings when we crept downstairs to watch cartoons as kids ourselves, the audience feels tethered to these kids and their adventure. At the start of the film, the glow of the light, the cereal bowls, the texture of the rug we colored our pictures on, there’s a magic quality in Skinamarink that takes us back in time to feel the overstated joy in the simplicity of these images and the irrational terror captured by others. In a scene where you hear the monster call to Kevin and hear him answer his youthful “hello,” your heart sinks, and your heart pounds.

Skinamarink‘s audio isn’t anything to write home about. All the dialogue is spoken in whispers, and many of the sounds are soft thuds. What makes it impressive is how loud the audio is to start. You can hear the audio pop and crackle, feeling tempted to raise the volume as it’s sometimes difficult to hear. This is by design, and it shouldn’t go underappreciated. If you can see it in a theater, where you’re not allowed to touch the volume, do it. If you end up watching it at home, play it loud on purpose. Some scenes employ found-footage elements that will make you jump a mile.

Ball’s film is going to be a love-it or hate-it film. It’s a slow, dread-inducing movie, abstractly achieved by creating a psychedelic and hallucinatory experience. The audience will feel the hairs on the back of their neck stand on end and propel themselves into a tense, anxiety-filled state whenever the film isn’t startling them with the trauma it imposes on Kevin and Kaylee. But I know some won’t find it as incredible as I do, and some will say it’s too abstract. I’m willing to admit it could shave off a few minutes, but it’s incredible how effectively this film makes the viewer feel uneasy and unsafe.

As the film stretches to its one-hundred-minute run time, the darkness glistens with a reddish color, becoming more threatening as less light inside the house exists, and many of the children’s creature comforts begin to vanish. The strobing effect from the television becomes the last bastion of normalcy in an otherwise warped home of violent requests. Skinamarink is not a bloodless affair, though you could watch the film with your kids—if you never want them to sleep again, that is. I’ll never look at that happy-faced telephone the same way ever again.

Ball has made a DIY nightmare look effortless, thanks in part to his brilliant cinematographer Jamie McRae. Everything here looks misshaped in the dark, twisted and demented, making the house a mystical place, eventually pushing beyond the reasonability of time and space. At the end of this mind-bending experience, you’ll fear the dark again and definitely have trouble falling asleep as you wonder if the light that burns brightly in a child can flicker out in the darkness too.

Skinamarink played as part of the Fantasia International Film Festival on July 25.

I recently watched the movie. Even though I wasn’t wow while watching it, I think it’s a beautiful and brave work on behalf of liminal horror and liminal spaces. It’s brave because there’s a lot of risk. It can certainly be an experience or a feast. I also don’t want to see cartoons and legos for a while. It’s an inspiring movie that I can’t get over for a long time.