I needed a bit of time to digest the insanity of Bloody Oranges (Oranges Sanguines). After watching the film, I pensively walked around my house, stretching the clump of pink and grey matter between my eyes because of how challenging the movie was. Since its premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, the internet has been busy writing up a storm both for and against the title. Bloody Oranges isn’t your typical film experience, and I understand why there is a diverse range of feelings about the film. Jean-Christophe Meurisse has created a thoroughly provocative experience, prodding the audience into a reaction, whether it be applause or disgust.

Sitting down to watch Bloody Oranges, I read the synopsis and thought I might have messed up when I requested the screener. The simple logline of the film suggests an amusing comedy about intersecting lives, stating, “A retired couple deeply in debt try to win a rock dance competition. A minister is suspected of tax fraud. A teenager makes the acquaintance of a pervert.” By and by, that is what the film is about if someone were to describe it in the broadest possible way. The experience itself is far different. In the introductory moments, the viewer is subjected to just a taste of what the film offers as dance competition judges begin rating the performances they’d just witnessed. The brief conversation incriminates these judges, who are doing far more than just doling out a score based on a dance.

The conversation swings wide and out from the scope of polite musings as the small group wax philosophical over the optics portion of their decision-making. The comments descend into jaw-dropping remarks regarding people with disabilities and end with an outward demonstration of pure outrage. The metaphor of what is being discussed behind closed doors is rather apparent. This is that locker room talk President Trump once discussed when he was unknowingly being recorded while talking to Billy Bush and confided in Bush that, when a person is rich, they can ‘grab a woman wherever they please.’ It’s as revolting to revisit as it was hearing about the first time, but it does provide the realism of where we are as a society. Later, Bloody Oranges quotes Italian Communist Party founder Antonio Gramsci in the middle of the film, saying, “The old world is dying, the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.”

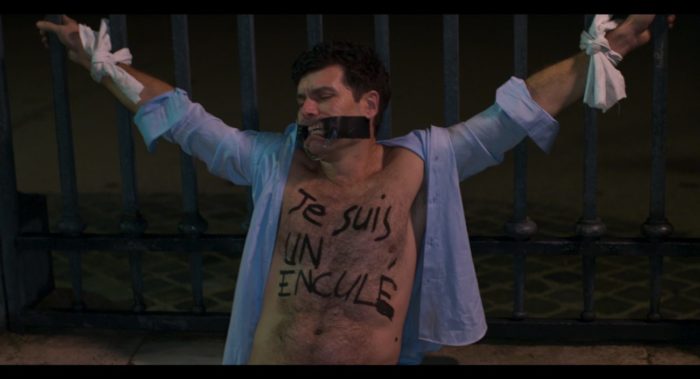

Even after the conversation, Bloody Oranges doesn’t exude the horrifying stylings a traditional audience is used to, going deep into discussions of justice, political finance, personal finance, virginity, and other divisive topics. I was fully prepared to admit I may have messed up and submit an article to our sister site, ready to review the social drama Meurisse’s film seemed to align with. When the aforementioned quote appeared almost midway through the film, the movie flipped to the dark half of its narrative, and the second part is entirely a horror film. A politician serendipitously arrives on the doorstep of a rapist after cutting pensions to reduce budget restrictions. The moralistic implication of screwing people out of what they’ve earned then becomes imbued in a very literal sense.

To be completely clear, that is not some unfunny attempt at making an inappropriate joke. That is the stark, difficult metaphor Meurisse is going for. As I said earlier, there was a lot of uproar over Bloody Oranges when it was first released, and I can’t imagine that was never the director’s expectation. Scrolling through the first few user reviews on Letterboxd, you’ll find a slew of one and two-star reviews that cite the film’s violence and misogyny as the main hindrances to its enjoyability. Where the film is labeled a dark comedy and was likely seen by many not expecting to be trolled with the societal-horror shocker they endured. As I previously mentioned, I wasn’t expecting the direction this film found itself going in either. Bloody Oranges is a bit of a roller coaster, ticking up a ramp until you see the quote, then rapidly propelling you downhill through a loop headfirst into a brick wall.

The result is a mashup of Paul Haggis’ Crash and Lars Von Trier’s Antichrist. Von Trier is someone who has also been labeled a misogynist, as well as a nazi, through his own subversive works and disturbing comments after being banned from Cannes following a joke about how he sympathized with Hitler. Meurisse is as much a provocateur through Bloody Oranges as Trier has been in getting people to react to him. Like them or hate them, you’ll surely remember them because of the shock value.

There will also be many people that will consider some of Michael Haneke’s more fatalistic works, such as Funny Games, as many of the violent acts are out of frame or off-screen, infusing them with further brutality as the imagination runs afoul of what could be happening. Bloody Oranges shows just enough of the violence to garner your contempt but only leans into it when it feels like suitable justification, what many would call the movie’s “good for her” moment.

I think Bloody Oranges isn’t fighting for one side or the other. The film never comes off as detrimental, but perhaps nihilistic. The film states these evils exist in the world in many forms through toxic words and behaviors that aren’t always in the package of who we consider the monsters are. The result of not being honest about why an elderly couple makes the finals in a dancing contest becomes the butterfly wings that begin this hurricane of overwhelming events. The couple needing the contest’s prize to pay off a debt are filled with hope and refuse to ask for help from their children, and we see how that ends up affecting a handful of people who seemingly have nothing to do with each other.

In the end, what I saw from the film was a unique balancing act that many will find unsatisfying, uncomfortable, and downright distasteful. I was not one of those people. Not all movies about balance will approach things from the perspective of Star Wars and lean on the side of its supposed heroes to please an audience. I feel the same way about Bloody Oranges as I felt about Antichrist when I first saw it. I’m honestly unsure whether it was a good or bad movie because the experience was a sensory overload. Bloody Oranges‘ acting is excellent, the film itself was well-paced, and I felt the themes and plot convalesced contiguously. As far as the film’s message is concerned, like art, this one belongs to the eye of the beholder, and everyone is going to see it differently. Plenty of films have divided audiences throughout the ages, most of which take the surface-level film into account and don’t dig any deeper. Bloody Oranges has a well of depth if you’re willing to follow it to the extremes it portrays. If Meurisse’s sole intention was to elicit a response, he sure as hell did. I crossed my legs and looked on through my fingers the same way I watched Sam Ashurst’s A Little More Flesh. To that end, the film will always be memorable and will probably start a few conversations, and that can be far better than being good but forgettable.

Bloody Oranges (Oranges Sanguines) is now available on VOD.