Ever since the live-action Cowboy Bebop dropped on Netflix back in November, the series has found its way back into both my mind and into the ether of pop culture in general, so let’s do what you should always do when you can’t get something out of your mind: thoroughly dissect it.

“But Tim, this is Horror Obsessive, why are you talking about Cowboy Bebop, that’s not horror at all!” Ah but you see, reader, you’d only be half correct. While it’s true that Bebop isn’t a full-on, twenty-four/seven horror series, by its own nature, the show jumped from one genre to another from episode to episode. Cowboy Bebop in fact has two episodes that fall into what we consider horror.

First off, there’s “Toys In the Attic.” Several episodes of Bebop have a plot directly influenced by some piece of western cinema—for example, ”Black Dog Serenade” is basically Con Air in space, and “Toys In the Attic” basically plays off as Bebop’s take on the one and only Alien—only the Alien is that thing in the back of your fridge that was thrown in three years ago and has long since been forgotten, not a seven-foot-tall H.R. Giger monstrosity. Go ahead and watch the episode if you don’t believe me. It’s somewhat of a more comedic take on horror, and while it’s absolutely a fun watch, that’s not what we’re here to talk about today.

No, my friend. Today…we’re going to talk about “Pierrot Le Fou,” a full-on nightmare that stands as not only one of Bebop’s finest moments, but as a rich, multilayered piece of horror that, to me, stands among some of the best pieces of horror I’ve ever seen—and once we’re done with that, we’re going to talk about something truly horrifying: the Netflix adaptation of this episode that thoroughly butchers it.

We’ve got a lot to cover, so let’s get started.

As YouTuber Mother’s Basement explains in an excellent analysis of Bebop’s iconic opening credits, each episode of the show tends to follow a similar set of story beats while subtly remixing them and discarding what isn’t needed to make it feel fresh each time. Each session of Bebop goes roughly like this: opening in the middle of a bounty hunt, with Spike playing it cool and trying to find a lead; a chase, usually leading to an encounter with the target when we least expect it; an overlooked element that leads to things taking a turn for the worst, almost always leading to some combination of kung fu brawl and gunfight that leaves the crew in freefall; new information emerging in said moments of violence that makes things somewhat clearer; a space chase; and finally a moment that knocks Spike flat on his back, leaving Jet to have to come and clean up the mess left behind. Trust me, this is all-important to know.

“Pierrot Le Fou” comes in at episode twenty out of twenty-six, right at the beginning of Bebop’s final stretch. By this point, we in the audience have (consciously or otherwise) become familiar with Bebop’s rhythm and the flow of each session, and the episode takes full advantage of this familiarity. It’s still Bebop, but it’s Bebop as it would be seen through a funhouse mirror. Almost all of Bebop’s typical story beats mentioned above are still present in “Pierrot Le Fou,” but each of them is distorted in a way that turns what is normally thrilling into something truly terrifying.

After a brief introduction to Mad Pierrot, we open on what is familiar territory—Spike, playing it cool. But he’s not on the hunt for a bounty, he’s just enjoying a night out, hustling a game of pool, and sharing a drink with a stranger. It’s a rare moment of calm, one that immediately gets undercut by a massacre happening just outside. Pierrot dispatches the men he has hunted down with terrifying efficiency—one of them had taken refuge inside a vehicle, and in one of the episode’s many horrifying visuals, Pierrot simply puts round after round into the same spot as the bulletproof glass bulges and finally breaks.

Spike, meanwhile, has stepped outside for a smoke—and exits the alleyway leading to the bar just as Pierrot has finished up his attack. The camera cuts through the key visuals of Pierrot’s still smoking gun and the pile of bodies left behind, but we only get a moment to take it all in before Pierrot turns towards Spike and opens fire on him. Spike shoots back, but a forcefield of sorts stops his shots about a foot in front of Pierrot, and the madman zips towards Spike to engage him in hand-to-hand combat.

Spike doesn’t just get beaten by Pierrot, he gets thrashed to within about an inch of his life. At one point Pierrot is practically juggling Spike in midair—and within a matter of seconds, Spike is on the ground staring down the barrel of a gun. This is far from the first time we’ve seen Spike in peril, but it’s one of the few moments in Bebop when we see a break in his demeanor of detached cool and possibly the only time when we see him truly terrified.

Just as blind luck is how Spike found himself in this nightmarish encounter, it’s blind luck that Spike even escapes at all—he’s only able to scramble away when a cat suddenly appears, setting off something in Pierrot’s mind and drawing his attention, and even then Spike barely escapes the encounter by the skin of his teeth. The hunter becoming the hunted might be cliche, but it’s an absolutely effective visual here—the typical Bebop pursuit turned on its head, with a panicked Spike running for his life instead of confidently running after his bounty.

This whole sequence plays out like a nightmare, made even more horrifying by the sheer chance by which everything happens. Pierrot isn’t a bounty that the gang is trying to cash in on, nor is he a terror out of one of their pasts. He’s simply a psychopath that Spike happens to cross paths with by being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Had Spike left the bar a moment later, Pierrot would have flown off and the two would never have met; had he left a moment earlier, Pierrot would still be in the middle of his attack and Spike would have likely decided to wait it out inside.

It’s a terrifying idea to be planted in your mind: that simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time could lead you into a nightmare. In addition, it gives us three of Bebop‘s typical story beats—the unexpected encounter with the bounty, the combination kung-fu/gunfight, and Spike getting knocked flat on his back—all in a matter of seconds and all in a way that feels wrong.

The next time we see Spike, following a scene of Jet getting the rundown on just how bad the news is when it comes to Mad Pierrot, he’s in remarkably bad shape, bandaged to the point that he can hardly speak or move. From the very first episode, Spike has been established as being almost unmatched in hand-to-hand combat, so seeing how easily Pierrot overpowers him and the aftermath of this attack strikes fear into our hearts. Spike remains in this badly wounded state for the remainder of the episode—after landing in Space Land, he hops out of his ship like normal, but this time he grimaces as he lands, grabs his ribs, then pulls himself upright before putting his hands in his pockets and trying to act like everything’s fine.

But, even in his badly beaten-up state, Spike still answers Pierrot’s invitation to join a “wonderful party” at a seemingly abandoned amusement park on the surface of Mars. The initial encounter between the two does feel like a blind, one-in-a-million chance encounter that would have never happened had even the slightest thing gone differently that night, but after that, something else takes over—something sinister. Spike and Pierrot are both drawn to each other, in a way that makes their rematch feel inevitable.

Pierrot’s mind, as we come to find out, has basically regressed to that of a child following a series of experiments conducted on him to try and make him into the ultimate killing machine. The project was deemed a failure, and it was ordered that Pierrot be kept in solitary confinement. He escaped and has long since gotten revenge on the ISSP directors who oversaw the project, but now he kills out of a savage mix of childlike curiosity and the sheer joy he finds in killing.

It’s why Spike—the only person to have seen Pierrot’s face and survived—becomes something of an obsession for the madman. Here is something new, something to be examined in the only way he knows how: violence. As Jet grimly notes after reading the ISSP’s files on Pierrot, there’s “nothing as pure or as cruel as a child.”

Michael J. Seidlinger, in a piece on “Pierrot Le Fou” for The Dot & Line, lays this out in a better way than I ever could: “A child operates on the prompts and peculiarities of emotion, unfiltered and pure. Happiness is sadness is confusion is nightmare; Pierrot’s aim to kill is his aim to relate, or at least engage, with Spike.”

A child will take a spider and remove each of its legs, not out of any malicious intent but simply out of curiosity, to see what happens. A child will say some of the most horrible things, not out of any desire to hurt but simply because they don’t know any better. What would be considered an act of cruelty is, rightfully so, treated as an opportunity to learn, to gain something, to grow.

But there is none of that for Pierrot. In fact, it’s the exact opposite: his mind is only regressing further. He’s trapped, unable to learn or grow from anything he experiences. So he kills, viciously, again and again and again, unable to learn anything from these encounters, unable to move on, unable to interact with anyone else outside of violence. He feels like a twisted, funhouse mirror image of human nature: a nightmare of the id running on pure, unchecked emotion and a childlike exuberance fueling his violent rampages.

As for Spike, we’ve seen time and time again that there is a dark, dark…something at the core of who he is as a person. Something that drives him to go headfirst into danger time and time again. Something that will someday get him killed—and that on some level, Spike wants to kill him.

It’s obvious to everyone around him—Faye initially tells Ed to keep the message a secret, knowing fully well that Spike would go right out to meet Pierrot, no matter how battered he might be. Spike tries to play off his musings to Faye and Ed about possibly not coming back from this one as just teasing, but there’s an unfamiliar, obvious hollowness to this defense. This time, Spike is truly afraid of not coming back—and that’s exactly why he can’t stay away.

As we find out in the Cowboy Bebop movie Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door, for most of his life, Spike lived without fearing anything—even death. It wasn’t until he met Julia that he came to fear death, because she made him want to truly be alive. As he tells Faye before heading out to confront Vicious in “The Real Folk Blues,” “I’m not going there to die. I’m going to find out if I’m really alive.”

Spike, too, is trapped. Bebop’s most consistent theme is that of being stuck in the past, and the detrimental effects of being unable—or unwilling—to confront it and move forward. Spike’s past, as we know, is his ultimate undoing. Not simply trying to outrun the Syndicate, but trying to recapture that feeling he had when he was with Julia, that fear of death that came with truly wanting to live. It’s why he runs towards certain death with a smile: to him, feeling on the brink of death is the closest he can get towards feeling like he’s alive. “Pierrot Le Fou” is so chilling because it plays on the very nature of our hero, and exposes the darkness at the core of his being.

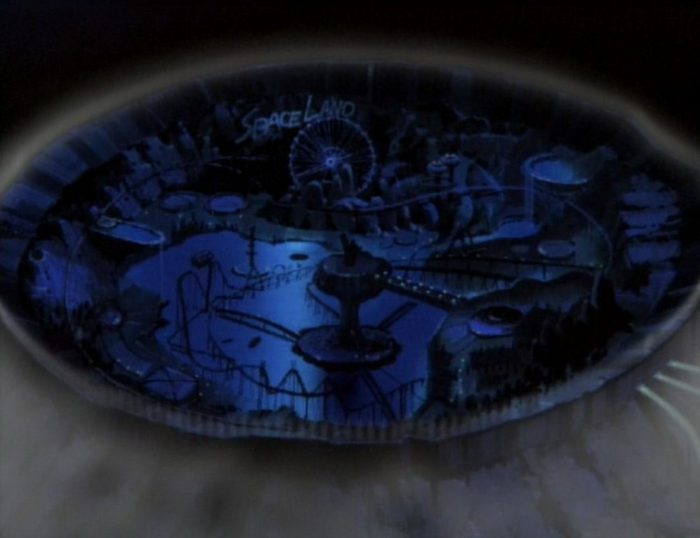

So Spike goes to Space Land, one of Bebop’s most memorable and unique settings. It’s basically Disneyland at night, but in space and in a style closer to Batman: The Animated Series, another iconic series that “Pierrot Le Fou” draws heavy influence from. Pierrot comes off like a mix of Penguin and Joker, and Space Land’s gothic architecture and heavy use of shadow that dwarf our characters feel closer to Gotham City than Ganymede.

Once he arrives, Pierrot greets him with an ecstatic “lettttttt’s party!” as Space Land comes to life. From here, the episode plays out similarly to one of Bebop’s space battles, giving the animation team an opportunity to show off what they can do. And show off they do: this sequence feels even more like a nightmare than the first encounter, filled with creepy animatronics, Spike getting dragged along a roller coaster track by his neck, and Space Land’s architecture nearly collapsing on Spike again and again as he scrambles just to try and survive Pierrot’s attacks, with the whole sequence being accompanied by the sour tune of a calliope and Pierrot’s near-constant maniacal laughter. Pierrot himself zips around less like a human being and more like a deranged, kinetic beach ball; a child’s idea of what such a character would look like in motion.

Meanwhile, Ed has hacked into ISSP’s database and pulled up the file on Pierrot. This flashback to the experiments conducted on Mad Pierrot is noticeable not only because it gives us insight into what made him what he is, but that it’s one of the surprisingly few moments in the episode that includes Bebop’s trademark: music. Not only is every other episode of Bebop filled with music, but music also is central to the show’s identity and feel—it spells this out for us in its opening credits: Bebop is meant to be Space Jazz. But music is noticeably absent from “Pierrot Le Fou,” instead the episode’s sense of dread is heightened by what little sound there is. Spike’s footsteps as he walks through Space Land seem to echo on forever, giving us an idea of just how big the place is.

When it finally appears in the flashback, instead of one of Bebop’s iconic, comforting jazz tunes it’s a skittering, nervous techno cover of a Pink Floyd song that only leaves us feeling more anxious as we watch Pierrot being experimented on. The flashback also gives us a key piece of information: there was a cat present at the experiments, which Pierrot now associates with the memories of his experimentation.

Finally, we get a twist on Jet flying in to save the day—instead, it’s Faye who comes flying in on her ship, and instead of pulling Spike out of the fire she simply winds up getting shot down by Pierrot as well. Even until the end, Pierrot is basically invincible, and it’s only the sight of another cat followed up by the glint in Spike’s eyes reminding him of the experiments that allow Spike to even wound Pierrot with a knife, leading to his disturbing demise.

Pierrot does just what a child would after finally experiencing the pain of Spike’s knife: he throws a tantrum, leading to the unsettling visual of him rocking back and forth on the ground, screaming “Mommy…mommy…it hurts…it hurts…” as the skyscraper-sized animatronics of Space Land’s parade draw nearer and nearer before one of them unceremoniously crushes him to death.

It’s an ending that’s quite frankly perfect for the episode. There’s no moment of discovery, no sudden insight into Pierrot, and no moment of triumph where Spike finally gains the upper hand. To the end, it remains a pitch-perfect piece of horror, one filled with meaning and one that tells us in no uncertain terms that our main character really had no business walking away from.

And then…there’s the live-action equivalent: “Sad Clown A-Go-Go.”

Think of all the things that made “Pierrot Le Fou” terrifying: the utter randomness of the encounter, Pierrot’s lack of motivation, the disruption it causes to Bebop’s established flow and rhythm, the sparse sound and lack of music, the horrifying imagery of an amusement park at night.

Out of all these elements, “Sad Clown A-Go-Go” really only keeps the horror imagery, and even that is extremely scaled back. Instead of the original Bebop’s Space Land, “Sad Clown A-Go-Go” takes us instead to Earth Land, a small, dinky run-down carnival. Now, there’s nothing wrong with a good small, dinky run-down carnival, especially in horror. But it’s a disappointing downgrade from Space Land’s awe-inspiring, almost gothic architecture and sense of scale that dwarfs both Spike and Pierrot.

The fundamental problem of Netflix’s Bebop adaptation is something I’ve taken to calling “Anakin Skywalker Built C-3PO Syndrome.” Simply put, it’s the idea that everything, no matter how small, has to somehow fit into the bigger picture and be connected to other elements of your show’s world. It’s prevalent throughout the series, taking previously independent stories and forcing them into the overarching “Spike vs. Vicious” storyline, and Mad Pierrot is the worst victim of this.

Instead of his inexplicable appearance and lack of motivation, here Mad Pierrot is a Syndicate asset, freed by Vicious and explicitly ordered to hunt down Spike. It’s a fundamental change to his character that robs his appearance of any deeper meaning and turns him into just another goon Spike has to face on his path to the inevitable confrontation with Vicious. An insane, near-invincible goon, but a goon nonetheless. The episode even misses the importance of Spike choosing to confront Pierrot the second time—instead of the simple invitation, Pierrot sends a broadcast via Ein stating that he has journeyed to take Spike’s life and threatening his crewmates if he doesn’t come to Earth Land.

There’s still the visual terror of his appearance, and the episode recreates several iconic moments from “Pierrot Le Fou,” but his encounter with Spike is effectively stripped of any deeper meaning—and the deeper meaning is where the true horror was found to begin with. It’s stunning just how badly “Sad Clown A-Go-Go” misses the point, and what made “Pierrot Le Fou” horrifying in the first place, and I wish they hadn’t adapted it at all rather than so thoroughly butchering it.

“Pierrot Le Fou” stands as one of the best episodes of the original Cowboy Bebop—not just a relentless piece of horror, but as a thorough disruption to everything we had taken for granted right at the beginning of the show’s final stretch. “Sad Clown A-Go-Go,” on the other hand, is a fundamental misunderstanding of horror, and an episode that doesn’t do any form of justice to its source material.

Looking for more horror episodes of non-horror shows? We’ve got you covered:

“Horror in Nickelodeon’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles”

“Ranking Every Halloween Episode from Community”

“How Boy Meets World Made a Better Slasher Than Most”