Hellraiser: if you don’t know it now, then you may never have. With a new film on the way and the shock appearance of Pinhead/The Lead Cenobite in Behaviour Interactive’s Dead By Daylight, Clive Barker’s body horror magnum opus is as significant in mainstream culture as it has ever been. Since its release in 1987, Clive Barker’s Hellraiser has steadily been making its mark across the horror genre. It exploded onto the stage of 1980s splatter with a startlingly baroque aesthetic and levels of nuance and viscerality challenged only by the best of its time.

And yet, despite this, contemporaneous criticism of the film was—perhaps equally shockingly—tepid. Despite its nine sequels, solo comics, spin-off novels, and remake pitches, Hellraiser has maintained a status as one of the lesser, or at the very least lesser-known, horror franchises to emerge out of the genre’s golden age; there is—in my mind—a very clear reason for that. Hellraiser is grotesque, ugly, messy, and, beyond everything else, queer. For something so often labeled “the one with the S&M demons,” what is actually at play is more monstrous, more surreal, and more connected to a queer cultural history than any genre titan. So join me today on a tour of the erotic nastiness of one of horror’s most foundationally queer texts. The box is open, all the pleasures of the world lie within.

Context: The 1980s, Splatterpunk, and AIDS

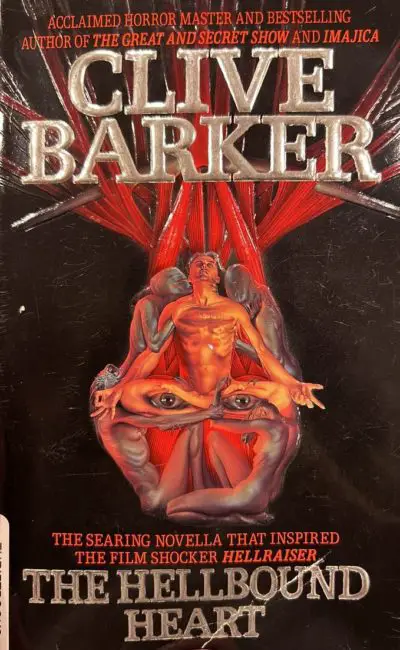

Let’s start by discussing the weirdness that defines so much of the text, Hellraiser is a work based on the 1986 novella The Hellbound Heart by Clive Barker, the man who would become the film’s writer-director. Before this, Barker had become a kind of a patron saint of what became known as the splatterpunk subgenre of pulp horror literature—a genre akin to extreme horror cinema, what David Carroll referred to in 1995 as ‘hyperintensive horror with no limits.’ These stories were nasty, aggressive, and in your face. They told tales of disturbed people and molten viscera—torture and suffering and body-horror presented for you, the audience, in graphic detail. Gone was the suggestive nature of the gothic, banished even was the mainstream workmanlike shocker violence of Stephen King. Instead, we give you sex and violence, often sex-with-violence, the graphic and the absurd in immaculate detail spiraling into new ways of torturing the reader, literature to make you sick, crushed under a stiletto heel, all served filthily for you on a moldering platter.

Splatterpunk, and thus Barker’s work within the genre, eschews suggestion, exploding it into masses of writhing bodies. Barker got his start working in this genre from 1984-85 publishing his spectacular Books of Blood—six horror short-story collections containing stories which time and again are subversive, weird, and queer (stories that you might recognize, such as The Midnight Meat Train, Rawhead Rex, and The Forbidden, which in 1992 became Candyman). It is through this genre that Barker endeavored in his work to push the boundaries of what is appropriate in a normative literary (and, eventually, cinematic) environment, especially during the 1980s. This was a period defined by the repression of radical identities under the shadow of capitalist excess and that era’s major ideologues, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, running political campaigns centering on “family values.”

In Britain—and in working-class regions like Barker’s own Liverpool—this repression became particularly obvious, with the AIDS crisis mediated by Thatcher’s government and the British press operating largely on the promotion of repression and the dangers, both moral and physical, of expressing homosexuality. AIDS was publicly renamed ‘the Gay Plague.’ (This would ultimately culminate in Section 28, a 1987 law that outlawed discussion of homosexuality in schools in the UK). By expressing outright those things which we bury, by speaking the unspeakable, Barker’s work, often dealing openly with—among other things—his homosexuality and subversive sexual practices, aimed to highlight the repressive tendencies of our censorious society by a socially conservative establishment (in the same way that other queer splatterpunk authors like Poppy Z. Brite would follow in the tradition of into the ’90s and ’00s).

Splatterpunk was a radical movement not just for its repulsion but also for its open excess against the norms of repression. It became queer out of a necessity to oppose the norms of a society not willing to acknowledge its own sexual underbelly, so much so that the queer and the gay were left for dead. And so splatterpunk, Barker’s splatterpunk, is that: sex and death, a memento mori with teeth, flesh seeking flesh in an unholy embrace.

The queerness of splatterpunk, the eager clawing at the underbelly of a repressive society, and the desire to shock through outright nastiness and an unavoidable connection with the bodily, reactive, and experiential, led Barker on the path to perhaps the most popular splatterpunk text of all time, and the subject of this essay: The Hellbound Heart.

Pleasure and Pain

Both The Hellbound Heart and Hellraiser, which were made in part simultaneously, are intensely bodily stories—dependent, as their characters are, purely on the sensory and the corporeal. They reek with the dramatic and overzealous, with Christopher Young’s absurdly indulgent score filling the space left by Barker’s extravagant prose in the novella. It is an arch tone, one emboldened by the symbolic heft of the Cotton household, almost too tall, too dark, too singular—a prototypical haunted house. The residents themselves emerge from that half-and-half fairytale place: Kirsty the beleaguered heroine, Larry the oafish and sincere father figure (doomed, of course), Julia the evil stepmother, and the monstrous beating heart beneath the floorboards. The result is a story that feels both familiar and hauntingly different—a narrative shorthand for “normal” paving the way for its subversion and collapse, the queering of the “universal” horror experience.

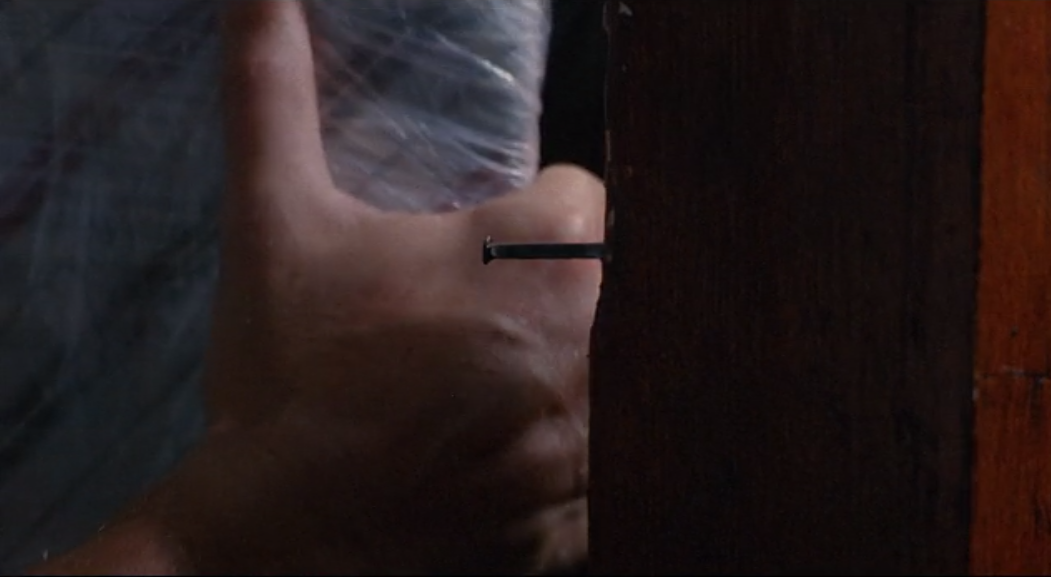

It is a story in one place; it is a house haunted not by any ghost but by sex itself—a half-imagined place, dwelt in by monstrous sex, by the sadomasochistic every-day. In other words, released in a society that positioned sexuality, especially queer sexuality, as the road to suffering due to AIDS, Hellraiser posits that all pleasure, even the normative “behind closed doors” expressions of the conservative establishment, contains within it a kind of pain, and vice versa—that the two are beautifully, hideously, interwoven. This is seen best in some of the film’s opening moments: a scene where Julia is deep in the lustful memory of her tryst with the now-missing Frank, while Larry attempts to heft a mattress up the stairs. At this moment sexual pleasure and deviant lust intersect with frustrated struggle; moans of pleasure are echoed in grunts of pain and anger; and finally, Julia and Frank orgasm, and a nail tears its way through the back of Larry’s hand.

It is in these precious intersections and consonance, moments of anticipation and climax, where lust and frustration become parallel explosions of bodily energy (and fluids), that cements the inseparability of the two—that pleasure cannot exist without at least a modicum of pain, that pain cannot exist without eliciting a momentary pleasure. We see this reinforced time and again. Larry, perhaps the most milquetoast heterosexual in all cinema, is shown watching boxing, cheering and jeering as others go through pain that they too get some enjoyment out of. Larry and Julia’s relationship is presumed to have bloomed lovingly upon their marriage but has soured since into a kind of dull mundane throb.

Pleasure and pain are, as Frank explains, ‘indivisible’; they belong to each other, in both mundanity as well as in their most explosive moments—and this is not even to speak of the supernatural. It’s this same kind of pleasure and pain that became integral to queerness during the AIDS crisis, and even now with the threat of discrimination, where self-pleasure and love come with the risk of loss always looming on the horizon, in queer life, the balance between pleasure and pain becomes normal. It becomes central to how we experience the world. What we see in Hellraiser, and what makes it so exciting, is this revelation that even the most standard moments of middle-class English life contain the same kinds of sadomasochism and outward emotion that are often condemned of queerness. The theory is that taking pleasure and pain together and exploring the sensory is not a negative but rather a core part of the human experience.

Even the film itself plays into this! Why do we watch horror if not for that same sadomasochistic urge? Why create or engage with splatter if not to construct those bodies of pain for some kind of self-pleasure, whether that’s intellectual or just damn fun? What else is that “PHWOAR” feeling watching a gnarly moment of creative violence if not a similar kind of pleasure-from-pain? This is not just the positing of a theory, it’s the culmination of one—a story of sensation devoted to making you, the audience, feel. The film becomes sex; it queers the relation between viewer and screen.

But, of course, this is not a barren family drama or an arthouse skinflick. It is a supernatural horror story and with that comes monsters. Terrible, beautiful monsters.

Frank, The Monster

Barker is quick to point out in his director’s commentary of the film that very little of his tale is intended to be truly ugly or disgusting, only to ‘scare the hell’ out of its audience. It’s clear to see this from the baroque beauty of its setting and characters. Frank, the stories’ inciting character, is a man devoted to pleasure in both the normative and antinormative senses—a life filled with the joys of risky sex and riskier drugs. Frank’s is a selfish pleasure, an odious kind of self-devotion that stalks him up to the story’s end. As he regenerates, he lies and deceives to achieve the cheap thrills of a monstrous kind of intercourse: a pseudosexual penetration at the expense of one for the joys of the other—a literal draining of what Barker only alludes to as ‘a kind of vital essence’ for his own gain. Yet despite this, Frank’s presence as a villain is not due to his pursuit of pleasure, nor to his selfish desire, but rather his suppression of it, the deceit that it entails from others but also himself. Frank is, in many ways, closeted. He is hiding from himself; he wishes to take pleasure without pain, to exact and not reap.

It’s this antinormative sexuality that Hellraiser does not condemn but instead generates, presenting a diversity of sexual exploration not confined to the normative throes of sweaty-man-upon-sweatier-woman, breasts buffeting the camera. The erotic is found in the dark, in the strange and absurd, in degradation and self-pleasure in dark rooms, in chains and hooks, pallor and leather, a diversity of sex that aches with its own pain and resonance—pleasure and pain spinning together, dancing in their own embrace. It is this queerness, the outright espousal of the pain that made queer love in the AIDS crisis precious—pleasure tinged with loss, lust inflicted with pain. Frank’s obsession is self-made, manufactured, closeted to the point where self-destruction is not enough. When he engages in those occult penetrations, he pleads with Julia not to look. He is ashamed of the sexual drives he engages in, of his new lust. Yes, he opened the box; yes, the Cenobites came for him, but he cannot grasp the connection, cannot come to terms with the erotic and ugly.

Frank instead subsumes to the repressive in dark rooms until it makes a killer of him.

Cenobites and the Queer Pursuit of Feeling

Openness of sexuality and self-expression make Hellraiser queer, the Cenobites being its heralds and priests. Emerging from a world (in later sequels called “Hell” but…come on…) that swells with ‘infinite pleasure and pain,’ the Cenobites are wretched and beautiful beings, once again toeing down the middle of a binary that is far more fallible than is comfortable. Their expressions, the visages of these priests play into exactly the same notions of pleasure and pain that inform the text. They are both brilliant and terrifying, beautiful and yet tattered with carefully sewn or left-open wounds, clothes wound within flesh within clothing: expression become being. Put another way, the Cenobites are what they want to be. They have achieved selfhood made of perfect pleasure and express that outwardly to the world. Very little about the Cenobites is hidden, and that comes to gender expression, too. The Cenobites are extraordinarily cross-gendered beings. They are neutral to the point of indefinability, gendering through pronouns and naming only done after the fact (e.g. “The Female Cenobite” is only known as such in the credits, and is referred to here as its original name: Deep Throat).

In the cosmic and calamitous place where the Cenobites come from, the place where they became Cenobites, gender is a performative choice—part and parcel with self-pleasure, the enacting of sex onto the skin. Sex is performed onto the body, it is a form of gendered performance at its most extreme: Pinhead’s phallic pins embedded in the skull, Deep Throat’s vulva a cavity in her neck, voices augmented to be supernaturally deep or scratchingly high pitched. It’s difficult not to see a trans reading emerge: utopian ideas of the pleasurable where the body becomes a canvas for true pleasure unbound by normative ideas of sexuality and gender, unbound even by the confines of the flesh itself.

When the bounds of normative sexuality fall away, so too does the social construct of gender. The Cenobites are transcendent becoming, a self made through the pursuit of antinormative pleasure, as if in direct offense to the world the box took them to; shown outwardly to the world, they are nightmarish only to those who take unkindly to their androgynous presence and sexual outwardness. This is monster—neither demon nor angel, priest nor defiler. A dizzying spiral of sensation and self, pleasure and pain beyond the hateful normal. New realities, new beings.

Frank runs from them because his entirely selfish and repressive hedonism cannot be squared with the Cenobites’ sublime monstrousness: he is too bound with sexual and gendered normativity, the facade of normality, to the point where he wears Larry’s skin as if to return to it. To be a “real man” again. But the mask slips, and Julia is expendable.

Beneath it, all that remains are senses too mediated, too repressed, a thunderous and self-destructive rage against the constructive, liberatory self-manifestation of the Cenobites and those in his way.

Summary

Hellraiser‘s connection with the monstrous, its adoration for dark corners and gaping chasms, and the Cenobites’ beautiful nightmarishness are exactly what make it such an excitingly queer text. It dares to prod at the outer reaches of sensation, dares to question the authority of a sexually normative establishment, and threatens any understanding of a fully understandable or rational world. Barker’s text sees the sensory, the shocking, the sublime, and the ugly as places for exploration to delve in rather than to hide from. You may have noticed the omission of Kirsty, the film’s protagonist, from this piece, and there’s a reason for that: she is a vessel. Like us, she is a spelunker in the sensory experience of this world, passing into pitch-black caves and out into the light, finding comfort that she knows what lurks in the dark places. The beauty that resides in the hideously subversive, and that considered hideous because of its connotations with loss and harm, is fantastical, with reaches beyond the human, powerful and fearful and sublime in ways that normativity can never approach.

As a queer horror fan, Barker’s work has always had a place for me, from its radical splatterpunk genre trappings to its positioning of ordinary queer existence—but where Hellraiser succeeds more than any other is by making queer pleasures and the pain that comes with them equally as important. Sensation might, quite literally, open up new worlds. A sensual touch might stretch the walls or bend reality until it breaks. There is a darkness and unknowability beyond our understanding, a world of feeling and surreality defined more by broad sensation than logic. Where men become dragons and carry puzzle boxes to new dimensions, where blood brings cowards back to life. There is an understanding that to feel is to live, no matter how harsh or terrifying those feelings may be, that sometimes ‘[pain is] what makes the pleasures so sweet.’

And so here we are, nine sequels in and with a reboot on the way, video game appearances that paint Pinhead as a slasher killer. Parody after parody, change after change, cash-grab after cash-grab. I’m not a traditionalist, far from it, but it is hard to not see how the sincere passion project of a queer creator has been milled into a shadow of its former self. It is now a text that, despite everything, still feels overwhelmed by what came after, one that remains subversive and cult, ever ignored by a normative establishment.

I remain optimistic about the next steps for Hellraiser, with a trans actor taking center stage and a sincerely talented director in the form of David Bruckner, but even with that hope and optimism, the impact and charm of the original will linger, no matter how much it feels tainted by what came after. Hellraiser was the film that made me fall in love with Clive Barker’s writing, his occult worlds, and their blatant queerness and sexuality. Let’s hope there’s still blood pumping in the veins of this straining, hellbound, heart.

Good job comparing homosexuals to sadomasochists.