Horror is my favorite film genre. The thing is, as much as I love the aesthetics that come with most of the movies of this kind, it’s the way storytellers can get through certain ideas in ways other genres can do but just not as effective. Yes, fear is a big part of horror most of the time, but so is humor or adventure or thoughtfulness. Or grief.

In 1969, psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross published On Death and Dying. In it, she introduced the five stages of grief, something she believed most who are either terminally ill or are losing someone close to an illness experience. This model was not really meant to be linear, nor was it meant to encapsulate what it means to face one’s own (or a loved one’s) mortality. The point was that human beings do not simply accept the loss of life.

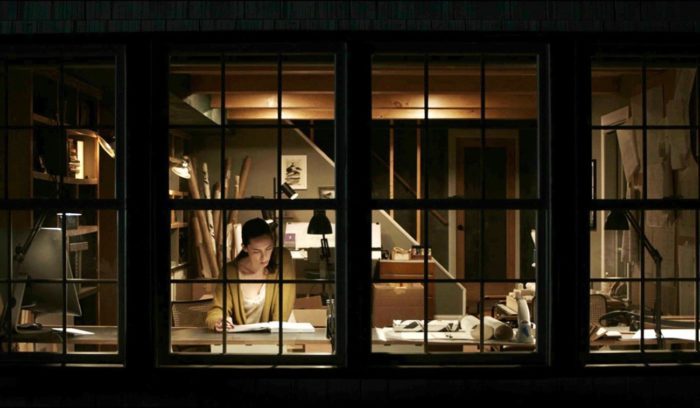

David Bruckner’s The Night House, released just a few short months ago, features Rebecca Hall (in another reliably fantastic performance) as Beth, who has just recently lost her husband, Owen, to suicide. From the opening scene, we know right away Beth is a person going through grief, with many of the so-called stages happening simultaneously.

This opening scene feels genuine and honest to me. I have lost a few people that I loved, and a few years ago, I nearly lost my older brother. I cannot fully imagine what it’s like to lose a parent the way my father and mother already have, but I saw their grief. I had my own, but it was different. When my brother nearly left this world for good, I must say, I had my fair share of tears just thinking about how damn close I was to losing him forever. But if I had lost him, what would my grief process have been?

It probably would’ve been different than Beth’s. I guess that’s what Kübler-Ross was getting at. We all grieve to some degree. Some go through the stages, others just a few. I went through some anger and depression, but also a little fear, mainly because my brother lived. Even now, I can’t get past the notion that he really can die at any time.

Just to be clear, the five stages of grief are:

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

Beth doesn’t go through bargaining, given her skeptical nature. After all, as she tells her friend, Claire, Beth doesn’t believe in an afterlife So it stands to reason that she’d take what happened with Owen as something that just happened. It was horrible, and she’s hurting. Still, nothing can undo it, and there’s no sense in making any kind of deal with anything or anyone because when we die, there’s nothing.

In one of the quieter yet powerful scenes in the film, Beth confides in Claire about her experience with death when she was younger:

Beth: “Afterward, when everyone would ask me when they found out [I died], like, ‘What was it like? What did you see?’ And I didn’t want to disappoint them, so I’d say, ‘I don’t know. I don’t remember.’ But I remember. Owen was the only person I ever told. There’s nothing.”

Claire: “What do you mean, ‘nothing’?”

Beth: “I wish I could tell you something. A light at the end of the tunnel. There’s just tunnel.”

Except, of course, for Claire, nothing is actually Nothing, which we’ll get to in a moment.

If The Night House was a prestige drama, tailor-made for Oscar gold, it would be focused on the stages of grief. Slowly, we’d see Beth comes to grips with what happened and find a way to live a life close to the way she used to. Thankfully, at least to me, this is a horror movie. As such, we are able to go through Beth’s internal journey in such a more rich and unique way.

For example, take her dreams. I don’t want to dwell too much on their importance to the story, plot, or Owen’s character, but it is interesting to note how they further explore the four stages Beth does go through anger, depression, denial, and acceptance.

In her waking life, Beth seems to process anger and depression in expected yet still unhealthy ways. She spends a lot of her time alone in the house she shared with Owen (who also built it), drinking and passing out in odd places like the bathroom floor. In a pretty wonderful scene at the high school where she works, we see her anger (held back, but still simmering) when she speaks to a parent. There’s not much in those instances that appears all that out of the ordinary.

However, in her dreams, she enters a mirror world where women who look like her are suffering physical trauma (death), which runs parallel to Beth’s emotional trauma. In these dreams, she’s still angry and depressed, but because of her denial of any real possibility that there’s an afterlife and that Owen’s ghost exists, she’s more curious than anything else, at least at the beginning of the film.

This leads her to curiosity in the real world, as she begins her search in finding out just who Owen really was. Was he interested in women who looked like her? Did he ever sleep with any of them? Does any of this have anything to do with why he killed himself? She needs answers to those questions.

Beth probably believes that Owen’s ghost, which seems to be haunting her, is most likely her subconscious trying to make sense of things, hence those dreams. She knows there’s nothing after we die. Yet, because we’re able to stay with her in her dreams when she answers a text or takes a call from Owen, we can see what’s inside her mind, rather than just seeing what she’s projecting to the outside world. Look at her in that scene when she answers the phone. She wants it to be Owen, but her denial is too strong. Again, at least in the beginning.

As the film moves along, though, so too does Beth’s grieving process. Her denial, less the version Kübler-Ross wrote about and more a literal kind of denial, slowly drifts away:

Beth: Why would [Owen] say there’s nothing? He didn’t believe that.

Claire: Beliefs change. Look at you. You’re the most skeptical person I know, and here you are, telling me that your house is haunted.

However, those pesky anger and depression stages don’t drift away.

It makes sense, of course. Beth’s curiosity ends up revealing that Owen was a serial killer, his victims the ones from her dreams. She’s depressed, not only about Owen’s death but about this part of himself that he kept from her. Heck, this is also why her anger can’t drift away as well. Yes, she’s angry that he killed himself, but she’s also angry that this other part of him was a murderer.

It’s one thing to let go of denial. It’s another to find a way past anger and depression.

Even when Beth finally begins to believe in Owen’s ghost, she calls out for him to do or say something, angrily muttering, “Motherf*cker,” when he doesn’t. Of course, when the time comes, in that infamous moment in the bathroom near the end, her anger and depression leave her. Owen’s ghost is real. There is an afterlife.

She lets go of herself in that bathroom scene, and whether I believe it’s Owen’s ghost or not doesn’t matter. She believes it.

Except it’s not Owen’s ghost. It’s the Nothing she saw when she died all those years ago. It turns out that the only way she can accept that there’s nothing after we die is to accept that there’s actually Nothing after we die. That’s some crazy symbolism that really only works in a genre like horror, where things are allowed to get crazy.

When Beth finally confronts Nothing, it’s quite the moment, story-wise, character-wise, and most importantly, thematically:

Beth: You’re not Owen.

Nothing: I’m what you felt when your heart stopped.

Beth: No. I felt—

Nothing: Nothing!

According to The Night House, there’s only Nothing after we die because that’s when our hearts stop. In other words, when we stop caring or loving, that’s when there’s Nothing. Otherwise, who knows?

For Beth, even at the end, she’s still not sure there’s anything. Maybe Nothing is not real. Maybe Owen was just a killer. Maybe he wasn’t. Maybe, maybe, maybe.

One thing she knows for sure, though, is that Owen was alive, and then he wasn’t. Owen was her loving husband, and then he killed himself. Any amount of denial, anger, and depression won’t change any of that.

That’s true, I suppose. As a whole, the five stages are a fairly selfish act. When I lose someone or ever get told the news that I’m on my way out, I might deny it. I might get angry and depressed. I might try to bargain with the universe because, unlike Beth, I do still believe in something after we die.

I believe the most important stage, though, is acceptance, and it’s always the last stage, regardless of how we process our grief. Because that’s the point of all of this. Beth needs to be out on that lake, in that boat with that gun in her hand. She needs to face Nothing in order to accept that Owen’s ghost was never real. She might very well be correct. When we die, there just might be nothing.

That doesn’t mean there is nothing in life. After all, it’s Claire’s voice that brings Beth back from the brink. Owen is gone, but Claire is still there. “It doesn’t matter,” Nothing tells her in the boat. “Let go.” Thankfully, she realizes that it does matter. As Claire pulls her from the boat and onto the dock, this exchange happens:

Claire: Beth? Are you here?

Beth: I’m here. I’m here. I’m here.

Claire: I got you.

Beth: I’m here.

Yes. They both are. We all are still here. For now.

Beth looks out to the boat, still resting in the lake. “What is it?” she’s asked. “There’s nothing there.” Her reply:

Beth: I know.

Acceptance is such a big part of the grieving process. Ultimately, we all get there sooner or later. It’s hard, though. Living is hard, but it’s living.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ five stages of grief are a way to look at how we come to accept losing our lives or dealing with losing those we love. Beth’s grief in The Night House took her on quite the journey in dealing with Owen’s death. She began in a dark place and though she seemingly ended up back where she started, with Owen still dead and the afterlife probably still nothing, she really doesn’t.

She knew there was nothing after we die. She knows that still. The difference is that, at the beginning of the film, she hadn’t accepted that. There is a difference between knowing something and understanding something. Luckily, too, she still has someone there for her. A lot of people don’t.

Horror movies can be fun, brutal, or some form of both. A lot of the time, though, they take concepts like ghosts or haunted houses and utilize these tropes to say something that an otherwise generic drama could do, just not as well, in my opinion. I could watch the drama version of The Night House, but I’m not entirely sure I would buy the film’s ending. I would know what the movie was telling me, that Beth made it to acceptance, but I wouldn’t understand.

The dreams, the interactions with Owen’s “ghost,” the house in the woods across the lake—these are things that allowed me to become Beth and grieve right along with her. I feel like I’m more equipped to deal with my grieving when the time comes thanks to a movie like this because the point of this process isn’t necessarily to get to acceptance. It’s the act of grieving that’s important.

Thoughtful and insightful. This movie was good but I didn’t appreciate the underlying complexity of the grieving process until reading this. Thanks.