Homo Homini Lupus Est

The psychopath—usually in the form of a serial killer—has been a fixture of not only the horror genre but of cinema generally for several decades. Indeed, cinematic depictions of the serial killer well precede the entry of the concept and its associated terminology into the popular consciousness in the late 1970s. Since that time, of course, on-screen serial killers have become ubiquitous. It is worth noting that the serial killer represents a very particular kind of psychopath; not all psychopaths are killers or even violent. Using a broader understanding of the term, we might consider a character such as Jordan Belfort (The Wolf of Wall Street) a psychopath. He exhibits trademark characteristics of the psychopath: an inflated sense of self-worth, intense self-centeredness, an insatiable need to satisfy his every desire, and an extreme callousness and disregard for other people.

Cinema no doubt has its share of characters like this—ones whose sheer rapaciousness makes them more wolf than man (in reality, rapaciousness is very much a human trait and not a lupine one, but no matter). However, invariably the psychopaths that most capture our interest are those whose pathology manifests in overt acts of violence. In other words, we like our wolves best when they do more than just bare their teeth. Among filmmakers fascinated by violent psychopathology—of which there are more than a few—perhaps none were more fascinated than Hitchcock.

Presumably, part of what intrigued Hitchcock about psychopaths is something that intrigues many people about them: their almost confounding propensity for the most monstrous behavior imaginable combined with the appearance of utter normalcy, even banality. The psychopath represents perhaps the starkest example of the disparity between appearance and reality. He (or, less frequently, she) is the monster among us, hidden in plain sight. At the risk of engaging in further wolf bashing—but in keeping with the lupine theme established thus far—the psychopath is the ultimate wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Good Old Uncle Alfred

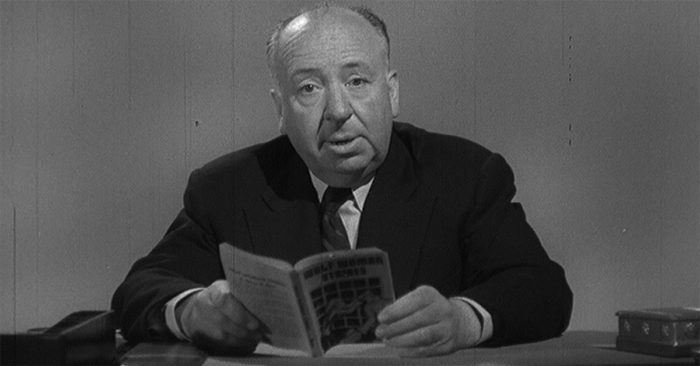

It is not altogether surprising that Hitchcock was fascinated by the psychopath as an extreme example of the duality of inner nature versus outward appearance. He himself was a man whose public image may have belied the reality of his darker inner passions. Certainly by the 1950s, if not earlier, Hitchcock was one of the most famous directors—if not the most famous—in the world. And, unlike many other directors, he was instantly recognizable to moviegoers thanks to his unique appearance, penchant for cameos, and knack for self-promotion. Whenever appearing in front of the camera, he was invariably clad in a suit and tie; in his speech, he was articulate, witty, and droll (and, of course, very English). His balding head, prominent jowls, and protruding belly gave him a decidedly round appearance. Together, all these qualities gave him the air of a kind of avuncular jokester—your proper, funny British uncle. And, in some ways, that is who he was. There is no reason to think these were merely elements of a carefully cultivated persona. The time and place of his upbringing all but assured a highly developed sense of propriety. And the sheer amount of humor—often awry, particularly British humor—laced throughout his films attests to a man with a well-developed funny bone.

He was, of course, also famously known as the Master of Suspense; but, even this moniker seems to reflect the once prevailing perception of Hitchcock as a kind of lovable rapscallion making thrilling but ultimately harmless movies for our entertainment. And, of course, he was trying to entertain us; but, when we take a closer look at his films—not least of which the film discussed here—we can see just how dark many of them really were. And once we begin to consider that darkness, we also begin to see a certain divide between perception and reality. While I believe elements of Hitchcock’s persona were genuine, a persona is still a persona; each of us has the ability to choose what we present to others—and what we don’t. Often, the most revealing moments are those in which we unconsciously give something away precisely because we think no one is watching or paying attention. Likewise, we give much away through our preoccupations—or, perhaps less politely, our obsessions.

A Motion Picture’s Worth a Thousand Words

I think this is especially true for artists; those who devote themselves to creating art are almost guaranteed to reveal as much if not more about themselves through their creations than through anything else they say or do. The themes, tropes, and motifs that crop up again and again throughout an artist’s work are bound to provide more unfiltered insight into what inspires them, what drives them, and what consumes them than even the most candid interview. And so it is with Hitchcock, I imagine. Of course, I am not suggesting that Hitchcock was secretly a psychopath because he dealt so often with them in his films; but, I am suggesting that underneath the formality of the suits and ties, beneath the intentionally and comically exaggerated stuffiness, and behind the fondness for silly puns and visual gags, there was a man with a singular fascination for the dark and gritty, the sordid, the aberrant, and even the abhorrent.

Furthermore, if Hitchcock ever did see glimmers of his onscreen psychopaths in himself, I suspect it was not because he saw himself as fundamentally different from the rest of us but rather as essentially the same. Perhaps what most intrigued him was the psychopathic potential in all of us and the difference—at once an unbridgeable gulf and a thin line—between those for whom these tendencies remain latent, tempered by morality but also fear of punishment, and those with no such compunction, those who yield to their inner darkness.

Uncle Charles in Charge?

One of Hitchcock’s early Hollywood films, one of his first set in the US, and his first to feature a proper psychopath (previous films had villains, but none that were truly psychopaths), Shadow of a Doubt (1943) tells the story of Charles Oakley, known as Uncle Charlie to his niece and namesake young Charlotte (Charlie) Newton. Uncle Charlie, on the run from the law, travels from the East Coast to the small town of Santa Rosa, CA to hide out with his sister and her family. Unlike the fugitives in many Hitchcock films, Uncle Charlie is no man wrongly accused of a crime he didn’t commit; on the contrary, it is fairly evident from the outset that he is guilty. Uncle Charlie is, we learn, a serial strangler of older, wealthy women, a killer the papers have morbidly dubbed the “Merry Widow Murderer.” Despite the fact that he makes little effort to conceal his psychopathy, and in spite of his consistently odd behavior and rather flimsy deflections, no one but his niece with whom he seems to share not just a name but some almost preternatural psychic link ever suspects he could be the serial killer the papers are talking about.

Eyes Wide Shut

The inability—or unwillingness—of people to see what they don’t want to see because it is unpleasant, inconvenient, or difficult is a recurring theme of Hitchcock’s and it’s easy to see how the idea of the seemingly benign psychopath hiding an awful truth lends itself well to stories that explore this theme. Shadow of a Doubt, with its story of a wolf in sheep’s clothing who manages with just shallow charm and a facade of respectability to pull the wool over the eyes of the quintessential small American town, is one of Hitchcock’s most effective uses of the psychopath trope; it’s also one of his boldest. While the film, in typical Hitchcock fashion, certainly delivers thrilling entertainment, it’s also a bit more than that, as Hitchcock’s films so often were.

More than anything else, Shadow of a Doubt is about evil coming into what is presumably the heart of goodness—the small American town—and not being recognized for what it is. It is this emphasis on the ability of evil to hide in plain sight—aided perhaps by the complicity of apathetic and wilfully ignorant observers—that makes Shadow of a Doubt possibly Hitchcock’s most poignant treatment of the psychopath as not merely an individual and isolated aberration but also as both a social phenomenon and symptom; it also is perhaps his best use of the individual psychopath as a stand-in for larger evils.

The New and Improved Hitchcock Villain: Now With More Evil!

As noted, Shadow of a Doubt is the first appearance of a psychopath in Hitchcock’s work. Importantly, Uncle Charlie is evil in a way that previous Hitchcock villains—thieves, spies, blackmailers, even other murderers—were not. That he is a murderer is, of course, bad enough on its own; but, there is more to it than that. Ostensibly, he kills these women for their money—we see him make a large cash deposit at his brother-in-law’s bank and he gifts his family expensive items, including a ring from one of his victims for his adoring niece—but it becomes increasingly clear that he is not interested in money; he even flatly says so at one point. Besides, someone killing for money likely wouldn’t choose a method as intimate and brutal as strangulation. So, what drives him to kill, if not money?

Unlike many Hitchcock films, there is little to no element of mystery in Shadow of a Doubt; as such the film tells us, in fact, Uncle Charlie himself tells us, why he does what he does. Throughout the film, his own words reveal both, directly and indirectly, his real motivations. This is never more true than in his two monologues—the first delivered to the Newton family at the dinner table, the second at a local dive bar to which he’s dragged his niece in order to confront her about her suspicions away from the rest of the family. These are two of the film’s most famous scenes and for good reason. The first in particular is genuinely frightening, thanks to the beautiful interplay of screenwriter and Our Town playwright Thornton Wilder’s chilling dialogue, Joseph Cotten’s performance that perfectly conveys the hatred and rage simmering just beneath Uncle Charlie’s calm exterior; and Hitchock’s camera that pushes slowly in toward Uncle Charlie’s face, bringing us literally face to face, eye to eye with evil.

The cities are full of women, middle-aged widows, husbands dead, husbands who’ve spent their lives making fortunes, working and working. And then they die and leave their money to their wives, their silly wives. And what do the wives do, these useless women? You see them in the hotels, the best hotels, every day by the thousands, drinking the money, eating the money, losing the money at bridge, playing all day and all night, smelling of money, proud of their jewelry but of nothing else, horrible, faded, fat, greedy women…Are they human or are they fat, wheezing animals, hmm? And what happens to animals when they get too fat and too old?

From this fairly short monologue, we learn something very important: Uncle Charlie hates women. He doesn’t kill them for their money; in fact, the money is entirely incidental. He is killing not to rob but to punish. In his eyes, these women have committed a grave offense, one for which death is an eminently suitable punishment. No doubt, there is more than a little of Uncle Charlie in the character of “Reverend” Harry Powell in The Night of The Hunter (1955). Powell also killed women—widows, in fact—for their money, but it’s clear there is something more than greed fueling his actions.

Well now, what’s it to be Lord? Another widow? How many has it been? Six? Twelve? I disremember. You say the word, Lord, I’m on my way…You always send me money to go forth and preach your Word. The widow with a little wad of bills hid away in a sugar bowl. Lord, I am tired. Sometimes I wonder if you really understand. Not that You mind the killin’s. Your Book is full of killin’s. But there are things you do hate Lord: perfume-smellin’ things, lacy things, things with curly hair.

Clearly, Harry Powell hates women; he’s even convinced himself that God hates them too and looks favorably on his foul deeds. Powell is just Uncle Charlie with the veneer of religion added. I suppose the unanswered question here then is: why do they hate women? While the driving factors behind misogyny are certainly worthy of discussion, it isn’t the discussion I want to have here so I hope it will suffice to say that Uncle Charlie and Harry Powell are simply (ha!) your garden variety misogynists with the likely laundry list of typical angry-man beef—feelings of inadequacy, impotence, sexual insecurity, and entitlement—turned up to 11.

You’re All Sheep! Or, Uncle Charlie the Edgelord

In Uncle Charlie’s second monologue, we learn that he is not merely a misogynist but a misanthrope—he hates everyone. He is also a narcissist; while it’s clear he thinks little of the world or the people in it, it is equally evident that he views himself as somehow separate, somehow above the rabble and the filth. What else but a profound sense of detachment and superiority allows him to judge others so harshly? The dreams of others are “stupid” (and how interesting that he seemingly equates “peaceful” with “stupid”) precisely because they are the dreams of “ordinary” people and Uncle Charlie despises ordinary people. To him, ordinary people are swine—bringing us back to his earlier description of the widows as “fat, wheezing animals”—and the reason why the world is a hell. He admonishes his niece to “wake up” lest she risks joining the ranks of the swine dreaming their stupid dreams. Implicit in this, of course, is the understanding that—in Uncle Charlie’s mind—he is not asleep; on the contrary, he is one of the few who are “awake” and who recognize the world for what it truly is.

You go through your ordinary little day, and at night you sleep your untroubled, ordinary little sleep, filled with peaceful, stupid dreams. And I brought you nightmares…How do you know what the world is like? Do you know that the world is a foul sty? Do you know if you rip the fronts off houses you’d find swine? The world’s a hell, what does it matter what happens in it? Wake up Charlie, use your wits, learn something.

It’s not difficult to see how this kind of delusional and inflated sense of self translates to feelings of intellectual and moral superiority. Uncle Charlie is a nihilist (“The world’s a hell, what does it matter what happens in it?”), but it’s clear he also believes that he matters, even if nothing and no one else does. He takes this philosophy to its absolute extreme, putting it into action by killing other human beings. Because he sees others as inferior, and because their very existence offends him, in his mind, they deserve it—and as a superior being, he believes he is entitled to act on his desires. Besides his superiority complex, he is also profoundly and hopelessly bored—by the world, by life—and murder is something to pass the time and perhaps make one feel alive, if only for a moment. Uncle Charlie’s boredom is existential and is born of a deep-seated disenchantment with all that the world has to offer. And, when the world has nothing left to offer him, Uncle Charlie’s recourse is to violently reject it and to destroy it—one life at a time.

Interestingly, in the film’s opening—during which we get the first of several instances of visual doubling between Uncle Charlie and his niece—we learn from a conversation between young Charlie and her parents that she too is somewhat disenchanted. However, hers is the typical disenchantment of youth, a passing phase in which she—along with millions of other teenagers—will bemoan the overwhelming mundanity and rote of day-to-day life. But where hers is temporary, surface-level, and entirely normal, Uncle Charlie’s is permanent, deep, and utterly pathological. Young Charlie is merely playing at being jaded and disaffected, just as her father and his friend—the nebbish next door—play at a kind of vicarious villainy through their passion for true crime stories and discussions of how best to get away with murder (of course, for all this they are as clueless as everyone else when it comes to Uncle Charlie).

Notably—though not surprisingly—young Charlie recoils at her uncle’s unmitigatedly contemptuous worldview; she does not share his contempt, in fact, she rejects it outright. Where she once was happy to think of Uncle Charlie and herself as kindred spirits, she comes to realize they are anything but—and is probably horrified to think they ever could have been.

Especially in this second monologue, we see in Uncle Charlie a striking resemblance to yet another future cinematic serial killer: John Doe from Seven (1995). Both are world-weary, self-righteous men who believe, thanks to their own twisted moral codes, that their actions are justified. Both also outwardly appear quite normal, even harmless; even their delivery is, for the most part, cool and calm, only slowly and subtly increasing in intensity—a hint of the roiling insanity just beneath the surface.

Innocent? Is that supposed to be funny?…Only in a world this shitty….could you even try to say these were innocent people and keep a straight face. But that’s the point. We see a deadly sin on every street corner, in every home…and we tolerate it. We tolerate it because it’s common…it’s…it’s trivial. We tolerate it morning, noon, and night. Well, not anymore. I’m setting the example. And what I have done is going to be puzzled over…and studied…and followed….forever.

Gut Alt Onkel Karl

Something that makes Uncle Charlie’s monologues even more disturbing is their similarity to Nazi propaganda, especially that related to Jews. To be sure, there is more than a bit of the Naziesque in Uncle Charlie, particularly in the way he adopts, consciously or not, a rather perverse form of the Nietzschean concept of the ubermensch. To Uncle Charlie, the women he describes in the first of his monologues, the women that he murders, are—above all else—parasites, just as the Jews were to Hitler. And the way to deal with parasites is, of course, extermination. Now, I don’t know if Uncle Charlie’s speeches were explicitly meant to evoke Nazism or not; Shadow of a Doubt was filmed in 1942 and released early in 1943, in the midst of WWII but before the discovery of the full extent of the Nazi regime’s campaign of genocide.

Interestingly, the war is for the most part conspicuously absent from the film. In fact, other than a shot late in the film of some servicemen going into a bar and some posters for war bonds, one could easily think there wasn’t a war going on at all. I wonder if perhaps this was intentional. Is the glaring absence of nearly anything to do with the war meant to emphasize the sheer—albeit superficial—goodness of the film’s version of Santa Rosa? Are we meant to see the wholesomeness of Smalltown, USA as a form of insularity, one pervasive enough to shut out even a world war? Perhaps. At the very least, it serves to make the arrival of Uncle Charlie and all the sordid darkness he brings with him feel even more like an irruption of all the world’s wickedness into the film’s ostensibly Edenic town (the film nicely literalizes this darkness as thick, black smoke billowing from the train he rides into town on).

In any case, returning to the parallels between Uncle Charlie’s dinner table monologue and the rhetoric of the Nazis, there is no question that the virulently anti-Semitic rhetoric and policies of the Third Reich were well-known to the world at this point (even if the citizens of Hitchcock’s Santa Rosa were no doubt blissfully unaware), so it’s not out of the realm of possibility that Nazism was among the real-world evils that influenced this particular onscreen depiction of evil. At the risk of going too far out on a whim, I will point out that there is also a scene in which Uncle Charlie attempts to kill his niece by gassing her in a garage; while I am willing to chalk this up to coincidence, I certainly think it qualifies as one hell of an interesting one.

Uncle Charlie, We Hardly Knew Ye

No doubt, the evil of Nazi atrocities might as well have been a million miles away from the film’s quaint and picturesque Santa Rosa, and thus easy enough to ignore. But what about when evil is in your midst? Surely then it can no longer be ignored. Except, in what is the most cynical and perverse aspect of the film, no one other than young Charlie recognizes evil when it is right in front of them. Not only does Uncle Charlie die with no one but his niece knowing the truth, the entire rest of the town celebrates him in death because of what they believe he was, namely a member of the extended town “family” who went out into the world, did well for himself financially, and eventually returned—bearing gifts—to home and hearth, kith and kin. This is all they know of him—but it is enough. The film seems to suggest it is people’s tendency toward being satisfied with only the most superficial knowledge and understanding that allows Uncle Charlie not merely to go undetected, mistaken for a normal man, but to be taken for a good man.

While Shadow of a Doubt certainly succeeds as a top-notch noir thriller, it also works as a nasty dousing of ice water to wake the audience from its own dreams—not “peaceful, stupid dreams” necessarily, but perhaps the dreams born of unguarded optimism and ingrained parochialism. The impact of the film’s stark cynicism is only heightened by its coming in the middle of the United States’ involvement in WWII, perhaps the closest the US and the world have ever been to a true battle of “good versus evil.” Given this context, one has to admire Hitchcock’s temerity in hinting at—if only indirectly—the capacity of good, regular folks (small-town Americans, no less!) to look evil in its bland, smiling face and merely to smile back.

Do you think young Charlie’s mother mentioning Uncle Charlie’s terrible accident (happening at some point in the past) was the studio’s attempt to give some sort of explanation for his dark, dark deeds? After all, they insisted that Hitchcock change the entire ending of Suspicion! Or was the mother’s brief monologue in the original, Hitchcock-approved script and storyboards? Thanks for a great essay, btw.

Hi, Sue. First, thank you for reading the article; second, thank you for taking the time to comment. That is a very good question and one I hadn’t even considered. I may have to look into it to see if I can find an answer because I’m curious myself. Your mention of Suspicion and Hitchcock’s having to change the ending certainly lends credence to the idea that the reference to Uncle Charlie’s accident was something “suggested” by the studio. Although, of course, it’s entirely plausible that it was in the script all along and had Hitchcock’s approval. Even in that case, I wonder to what degree, if any, Hitchcock would have considered it a key piece of explanatory (let alone mitigating) information. I’m reminded of the much-maligned monologue by the psychiatrist at the end of Psycho. While it’s easy to see it as a bit of overly neat and tidy wrapping up and explaining away of Norman’s “dark, dark deeds,” something (not least of which is my sense of Hitchcock’s own sensibilities as both an artist and a person) has always suggested to me that Hitchcock was well aware of the pat nature of the explanation, indeed of the entire scene. The film itself suggests this too–significantly, the film doesn’t end on the doctor’s explanation, it ends on Norman and Norman/Mother’s internal monologue, and the final shot is Marion’s car being dredged from the swamp. A downer, “no one was saved” ending if ever there was one and certainly NOT in line with the “A place for everything and everything in its place” ending only superficially suggested by the doctor’s speech. I think Hitchcock knew–and I think he knew when he made Shadow of a Doubt–that for all the talk of “reasons” and “causes,” when dealing with the human mind, and particularly its darker recesses, we actually know very little; as such, we are, often, merely trying to offer explanation for what may ultimately be inexplicable. All that to say that, whatever its origin, I don’t think Hitchcock would ever have believed that any “accident” (kicked in the head by a mule while growing up on a farm?) was truly to blame for Uncle Charlie doing what he does. Anyway, thanks again for taking the time to read it, for your thoughtful question, and for your kind words.

Now that , was one fine essay ! … nice to recall these gems, even better to have a superb narrator walk you back thru them … marvelous insights, everything is there… cinema history ( more than fifteen years before PYCHO ! ) pychology ( ever think about shrinking the master of darkness?! …) geography ( aint little Santa Rosa just picture perfect with a smokin locomotive bringin home son home ! ) hematology ( yes , there must be blood , there are real murderous things going on ! ) … and all this, and so much more ! … I love this chronicler, do you ? ….

Excellent article! I saw Shadow of a Doubt (and Night of the Hunter) a long time ago and consider them among the earliest and most chilling film portrayals of psychopaths in action, and are long overdue for a re-viewing!

I find many (if not most) contemporary depictions of the psychopath so overt that they are frustratingly caricature-like, perhaps to intentionally maintain the fiction that this is outlier behavior ? Yet, the sheer volume of examples of real-life psychopathic behavior, exhibited both on a grand scale and individually go unrecognized / unacknowledged by most people and continue to be viewed as aberrations.

Well said! Thanks!