Cults in horror are nothing new, and at this point the story of Jim Jones and the Peoples’ Temple is so ingrained into modern culture that even people who aren’t necessarily familiar with its story still use the phrase “drink the Kool-Aid.” Most of the time in horror, cults are used as an antagonistic force and are often depicted as being a collection of people who have been brainwashed by a charismatic but unpredictable leader. This is why I was so surprised by the indie title Sagebrush. On the surface, it covers almost no new ground on the topic of cults and fanaticism. Its trick is in how it approaches the subject matter from an interactive angle, and how its familiar themes impact the player by way of that interaction.

Sagebrush has you play as an at-first unnamed protagonist as they explore an old ranch that has long since been abandoned. Right away, the game creates a weirdly serene and laid-back atmosphere with its exaggerated pixel graphics. Similar to full-on horror titles that use a deliberately dated aesthetic, the low-fi graphics allow the player to fill in the small details on their own. They’re given enough information about the surroundings to let their brain complete the picture, and the result is an oddly beautiful setting.

This is the game’s first great trick. The countryside you explore is quiet, with only the sound of the player’s footsteps and sometimes the wind to remind them that they aren’t in a nostalgic dream. But it becomes clear very quickly that something went wrong at the ranch. There are plenty of notes to find lying around the game world that fills in the history of this ranch, and lots of classic tropes are put to effective use here. One of the first buildings you explore is the school which is packed with religiously themed learning materials for the children to consume. There isn’t necessarily anything that raises red flags, though.

These early moments in the game are important to what the story does later on and suffice it to say I’m going to be spoiling most of the game’s major revelations. This is among my favorite indie titles in recent years, and I do think that going into it not quite knowing where it’s going is the best way to experience it.

Anyways, it soon becomes clear that there was much more going on under the seemingly idyllic surface. It’s hinted early on that one of the members you read about is not what he seems and sure enough, it’s eventually discovered that he is an undercover cop trying to determine if there is anything nefarious going on in the commune. This sparks paranoia amongst the cult, and soon you find evidence of a sort of witch hunt. People documented their own fears and what it could mean for them if the outside world corrupts the supposedly peaceful life they lead.

It’s why the early moments of the game are so important. The aesthetic is pleasing and relaxing, and it’s easy to see why a group of people might fall in love with such a location. Not only that, but you also learn that most of the members carry with them some sort of troubled past. There’s nothing out and out crazy about any of the members, but they all have suffered because of their place in the world. It’s not difficult for the player to sympathize with them and understand why these people might seek refuge in something so scary as a cult. Like most religions, it’s a comfort, something bigger to believe in that helps them cope with the struggles of everyday life.

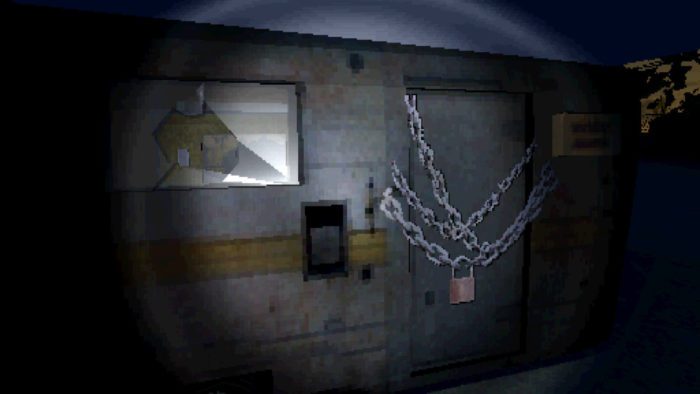

The problem is that even ignoring the outside influence of the undercover cop, the very core of the cult is corrupted. It’s led by Father James (wonder where they got that name from) who, as is per usual with these kinds of stories, uses his position of perceived power to sexually exploit the women in the commune. There’s a sequence where you go through his house, which was always kept under lock and key, and you find porno mags and even drug paraphernalia amongst his possessions. Despite all of his posturing as a prophet for the lord, he is just as damaged and flawed as the rest of his flock, and that damage is what leads to the cult’s eventual downfall.

Late in the game, you travel into some mines and discover a whole weapon cache the cult was planning on using should the law ever come after them. By this point in the story, it’s revealed that the undercover cop was murdered by a few of the cult’s members, and this led to the downward spiral that led to the mass suicide mentioned in the game’s opening. Due to everyone’s beliefs, they thought it was the outside world that led to them needing to die, but the problem is that they all brought a little of the outside world with them.

In this way, the game becomes a sort of modern version of the story of the Garden of Eden. The cult members created their commune and followed Father James because they felt lost and abandoned by the outside world. They fled to the beautiful countryside in hopes of creating their own personal paradise, but never realized they were secretly serving the whims of a manipulative sociopath. And in an interesting move, Father James is written in a way such that you get the impression he believes his own myths. By the point in the story where the cult commits mass suicide, it’s clear that Father James truly does believe he is some kind of prophet, and that God is commanding them to enter Heaven. It’s a fascinating twist on the Garden of Eden, and weirdly reflective of its conservative themes. Sagebrush seemingly puts forth that the very idea of a paradise is impossible since humans are such inherently flawed creatures.

This being a video game, though, the player character is a mystery that is saved until the very end, where it’s revealed that you are controlling Lilian, the cult’s sole survivor. She has struggled all her life to reconcile with what happened at the ranch, where it is revealed that the cult locked themselves in the church on the hill and set themselves on fire while Father James killed himself in his bunker. The game ends with Lilian calling her husband and explaining that she has some things to tell him. Then she recounts how she first got involved with the cult by meeting one of its members Anne at a bus stop, and the rest, as they say, is history. She has come to terms with everything that happened, and the game ends overlooking the valley where so many people killed themselves.

As I said earlier, from a pure plot perspective, there’s very little that’s new in Sagebrush. In fact, the player knows going into it that the cult killed themselves similarly to the Peoples’ Temple. But I think there are two main points that help it feel fresh and new. One is the aforementioned setting, which comes across as beautiful at first glance but slowly reveals its troubled past to the player. The other is Lilian herself. Even though the player doesn’t know they’re playing as Lilian in the beginning, they’re able to reflect with her on the events of the story before they even know the specifics of what happened. The familiarity in the game’s plot is used to the story’s advantage in this way; the game isn’t really about the downfall of a cult so much as it’s about laying the (very troubled) past to rest and moving on from what once was.

This is the game’s greatest trick. The story of Jim Jones and, indeed, the story of Sagebrush is extremely depressing and a rather damning account of how humans behave. But Sagebrush takes those awful, terrifying events and forces the viewer to consider them from the angle of someone who lived through them. Much like the outstanding film by Justin Benson and Aaron Moorehead, The Endless, the cult in question isn’t immediately recognizable as an antagonistic force. The early parts of the game are somewhat welcoming, if isolated and a touch creepy. It isn’t until much later that the full extent of their evil is shown, and when it is, it’s terrifying.

And I think that is why Sagebrush hit me so hard. Even though it’s derivative of many cult stories both real and fictional, it shows that, at the end of the day, cults are made up of human beings. It’s so easy to look at a story like Sagebrush and wonder what would ever possess someone to join a cult. It’s easy to tell yourself that you would never do anything so clearly misguided. But Sagebrush forces the player to consider it from the angle of someone who has been so let down by the world that acting as a sex object for a sociopath who views himself as a savior is more appealing than functioning in what we call a normal society. It instead suggests that most people are just a few instances of bad luck from following down the same path as Lilian and so many others. That is, to me, what makes Sagebrush so special and effective as a piece of cult fiction.

Looking for more on indie horror gaming? We’ve got you:

“Heaven Dust Is an Infectious Tribute to Resident Evil”

“Drawn Into a Bad Dream: Coma”

“25 Days Later Review: Tamashii”

“Cry of Fear: The Scariest Game You’ve Never Played”

“WORLD OF HORROR Gets Massive Update, Available Now”

“Kick Ass for the Lord in Forgive Me Father”

“Devil Daggers and Spooky’s Jumpscare Mansion: Two Visions of Repetitive Hell”