Contains spoilers.

I feel like something bad is going to happen to me. I feel like something bad has happened. It hasn’t reached me yet, but it’s on its way.

These are the solemn, paradoxical words that open Joel Anderson’s first and only feature-length film Lake Mungo (2008), and they aptly set the tone for this morbid tale of grief and inescapable truths. The film takes place in the Australian city of Ararat and revolves around the drowning of a young girl, Alice Palmer (Talia Zucker), in the local dam. While her family struggles to come to terms with their loss, they are confronted with the possibility that Alice has returned in some way and is haunting their home.

The narrative is presented in pseudo-documentary form, unfolding primarily via interviews with Alice’s friends and family, but there are also elements of found footage as more evidence and information is revealed. With its slow pace and simple story, it is easy to write the film off as anticlimactic and uneventful, yet the camerawork, soundtrack, and pacing all come together to create something that gets under your skin without you even noticing.

Straight away, we get the sense that this could be a real scenario happening to real people as we are shown interviews with Alice’s family members and friends alongside news coverage of her disappearance. These interviews and the home footage of Alice and her family that is shown alongside them help to humanize the characters, building a sense that they are people we know.

Music is also used consistently throughout Lake Mungo to help set the tone, and in the beginning, it is quite soft and mournful to match the family’s grief. As the unsettling possibility of Alice’s ghost haunting the family is introduced, this changes to a much more ominous droning hum. Often these spikes in the dark musical ambiance are accompanied by a slow, deliberate zoom into a family photo, eventually focusing on Alice’s face.

Even before we reach the overtly supernatural elements of the story the film is saturated with feelings of despondency and malignance. The sense of loss and hopelessness that the Palmers feel is amplified by frequent shots of empty spaces. Despite their emptiness, these shots hold so much emotion within them as the somber voiceovers talk about the experience of losing a loved one. One of these spaces that is revisited throughout the film is Alice’s bedroom. A particular shot near the beginning shows the sunlight slowly dimming in the room, giving way to total darkness, just like Alice herself vanishing from her family’s life.

Seeing Alice’s empty room also contributes to a sense of knowing her somehow, perhaps because a bedroom can provide an intimate window into a person’s personality. It feels lived in; there are posters on the wall, books on the shelves, and drawings presumably made by Alice herself. All things you might find in any ordinary teenager’s room, making the sense of loss feel all the more personal and profound.

There are suggestions of supernatural goings-on at the beginning of the film via mentions of odd happenings around the house and mysterious bruises appearing on Alice’s brother Mathew (Martin Sharpe), but when Mathew discovers what appears to be an apparition of Alice in one of his photos, the film takes on a much more eerie tone.

To make matters worse, this discovery is followed by the retrieval of Alice’s bloated, almost unrecognizable corpse from the dam, making the photographs with the ghostly figure all the more ominous and putting to bed any hopes that Alice could still be alive. To investigate further, Mathew sets up cameras around the house to see if he can record any further evidence of a ghostly presence.

The introduction of Mathew’s camera footage gets the ball rolling in terms of explicit horror within Lake Mungo. The footage is grainy and low quality which actually makes the appearance of a ghost even more unsettling—we can’t quite see the details of the figure, but our minds fill in the rest. Director Joel Anderson deliberately plays off our tendency to seek patterns in a given image that look familiar to us, that resemble a face of which we can make sense.

In each of these dark, pixelated images our eyes scan the room for any possible ghostly outline. When we find it our first instinct is to look away, to deny the disconcerting reality of what we are being presented with, but the camera gives us no such option. It instead zooms in continually to the distorted face of Alice as the fuzzy, doom-laden music intensifies, forcing us to reckon with her unnerving presence.

We also are introduced to the character of Ray (Steve Jodrell), a man working as a psychic who supposes that death is not a ‘full stop,’ but merely another phase of existence. He’s a somewhat ambiguous figure, giving very general mystical advice that could apply to a broad range of circumstances, and withholding information about Alice (who was a previous client) from the Palmers. Nevertheless, Alice’s mother June (Rosie Traynor) goes to partake in a guided meditation with Ray in the hopes of connecting with her daughter somehow.

She describes walking into her house, and we see slow pans of the empty hallways as the haunting, gloomy music returns. June says that she can see Alice’s shoes outside her room, and once inside sees Alice sitting in the chair at the end of her bed with a saddened expression. It’s a heartbreaking moment, showing how futile her efforts are to connect with her daughter.

Ray suggests holding a séance to the Palmers as a way of reaching out to Alice, and despite their initial reluctance they decide to go ahead with it. Mathew records the séance and, lo and behold, upon viewing the footage, a ghostly figure appears at the edge of the frame that has even more of a likeness with Alice than before. Just as it seems undeniable that the ghost of Alice is indeed haunting the house, we are hit with the revelation that Mathew has been doctoring the footage and photographs of Alice.

This briefly puts us in a state wherein we think we are safe from the supernatural implications of the narrative—there is no ghost, so the source of the horror is eradicated. Mathew seems remorseful that his misguided attempt to bring closure to his family has, in fact, done the exact opposite and caused more harm than good.

The news comes as a particular blow to June, who has many regrets over Alice’s death as it’s revealed that they had a strained, emotionally distant relationship. They are described by others as being very alike, both preferring to keep to themselves and adhere to a strong sense of privacy. Even the grandmother seemingly has a strained relationship with her daughter, admitting that she has never been able to give herself wholly to her and that this coldness was inherited by both Alice and her mother. This sense of generational dysfunction is a major theme in the film and makes Alice’s death feel like even more of a premature tragedy.

Another revelation comes with the discovery of the Palmers’ neighbor lurking in the corner of one of the shots from Mathew’s camera. This leads them to find a videotape showing that Alice had much darker secrets than expected and that she was in fact engaging in sexual acts with the older couple next door. The family photos of Alice looking happy and carefree that follow now serve as a stark reminder that people’s appearances can be deceiving, that you may never really know a person, as evidently no one truly knew Alice.

None of her friends seem particularly sympathetic to her experiences, and neither does her mother, who chooses to speculate on the reasons why Alice got involved with the neighbors and if she was in love with either of them instead of having sympathy for her victimization. The people around Alice cast her as very secretive, almost resenting her for the fact that she didn’t tell them everything rather than considering what a difficult position she was in.

Lake Mungo comes to be a central location of the film, and in some ways is at the very core of the mystery. We are told that Alice went there on a camping trip several months before she died. We see phone footage of her friends laughing and having fun at the camp, but Alice seems to be much more withdrawn and downcast. At one point, she walks away from the group, seemingly distressed by something, and can be seen on camera burying something under a tree. The family decides to go to Lake Mungo and unearth whatever it was that she buried, causing them to find a plastic bag filled with Alice’s phone and a few of her favorite items.

As the footage on Alice’s phone is revealed we are shown different footage of Alice in Ray’s office as he asks her if she is scared of dying, to which she answers “of course, isn’t everyone scared of dying?” Ray asks her what happens in her dreams, and she responds with the same words that were spoken at the beginning of the film. While she speaks, describing the feeling of something bad coming toward her, we return to the phone footage and see a pale figure getting closer and closer to the camera.

In the single most terrifying moment of the film, we realize that the figure is Alice herself, only the bloated, dead version from the lake. She is being confronted with the terrifying, inescapable reality that she is going to die. The existential ramifications of seeing your own corpse from the future are dizzying, to say the least, made all the sadder when you realize that Alice kept this reality entirely to herself.

The use of voiceover to connect the past and the present is something that occurs throughout the film, and the coinciding timelines contribute to a sense of fate and inevitability. Near the beginning of the film Alice’s mother, June mentions a nightmare she has where Alice stands at the foot of her bed still drenched from the dam, not saying anything.

Later on, June reads out one of Alice’s diary entries where she describes the exact same nightmare, but from her own point of view. This shows that despite the emotional distance between Alice and her mother they were connected in a way they didn’t even realize (until it was too late). In a way, their dreams and visions intersect to form a type of communication that they weren’t able to have physically.

After the harrowing footage from Alice’s phone is revealed we again see shots of the empty rooms and hallways in the house, only this time it is paired with audio of June describing a newfound sense of calm and closure. She says that they are beginning to feel like a real family again. The music is now more serene and pensive, matching the tone of the family choosing to move forward and start anew. June decides to visit Ray one last time for closure and again enters a guided meditation.

She describes entering the house and walking down the hall to Alice’s room. This is intercut with footage of Alice’s own consultation with Ray, where she is describing someone coming down the hall. Alice describes seeing her mother, who is not saying anything, evidently doesn’t even sense that she’s there. At the same time, June confirms to Ray that Alice is not there in her vision. Alice describes June leaving the room.

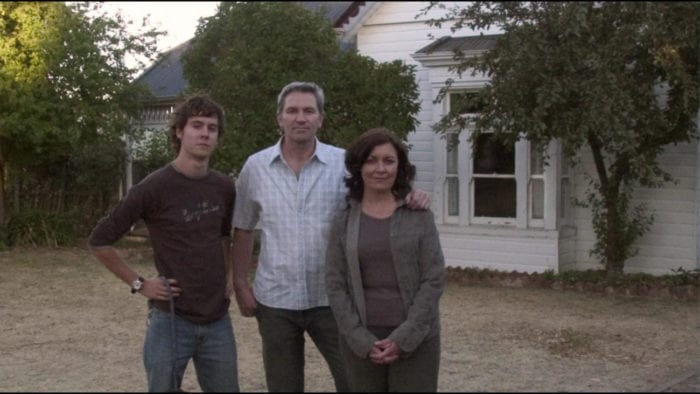

Across different moments in time, the spectral forms of Alice and June struggle to connect, with Alice feeling a sense of abandonment and detachment just as June is feeling a sense of relief and closure. The final shot shows the Palmers standing outside their house taking one last photo before they leave for good. The camera slowly zooms in to the window behind them which shows yet another specter of Alice, separated from the rest of them.

It’s one of the most heartbreaking endings I’ve ever seen, and there’s such immense sadness to the way Alice is effectively being left behind and forgotten without being able to do anything about it. Her family has gained closure and ironically feels closer to one another due to overcoming her loss, whereas Alice is alone, having failed to make them aware of her presence.

Lake Mungo is an unnervingly effective look at how ghosts can be used as a way for people to cope with grief, exemplified by the constant back and forth between evidence being portrayed as real and then debunked, calling into question the legitimacy of the plot. It also raises issues of mortality and being confronted with the reality of your own death and being forgotten by those around you.

Grief is an uncomfortable topic to examine, but Anderson manages to paint one of the most accurate and empathetic portraits of it. Even though we only see and learn about Alice via interviews, photos, and old video footage, we still feel like we know her and can relate to her struggles, to her unspoken secrets that alienated her from her peers.

Our relationship with technology is also a prominent theme in the film—the way it can immortalize a loved one even after their passing, capturing an image forever, and in effect, resurrecting someone from the dead on demand. It’s one of those films that seems almost forgettable upon finishing it until it all catches up to you at once and suddenly you can’t stop thinking about it.

The atmosphere of dread and despair hangs heavy over the film, quietly and patiently leading up to a crescendo of existential terror. It’s not in-your-face scary but something much worse, settling down in the pit of your stomach along with all our discarded, dormant anxieties. Although it’s definitely a slow burn and the bone-chilling implications of the plot may be too subtle for some, like the title, it has a wealth of depth underneath the surface that will drag you down if you let it.

I feel like something bad is going to happen to me. I feel like something bad has happened. It hasn’t reached me yet, but it’s on its way.