Resident Evil 4 was the very definition of a game changer, both for its series, and the gaming industry as a whole. Not only did it completely change the series’ core gameplay, but it ushered in an era of titles that tried (and failed) to capture its success. It’s also a shockingly popular entry, with it having been ported to pretty much every platform imaginable. Including the iPhone.

That’s enough preamble. You know that Resident Evil 4 is a masterpiece. I know that Resident Evil 4 is a masterpiece. What more can possibly be said about it that hasn’t already been said? Why bother with this article at all when the world knows how big of an impact this game made when it landed?

Aside from the fact that we’re currently in the middle of a Resident Evil retrospective series, I want to take a different approach to the usual discussion of this game. Of course I’m going to dive in to what makes it so great even to this day, but I’m also going to turn a critical eye to what it did to its own series and the gaming industry. We’re taking a look at the best and worst parts of this classic horror shooter, and examining its staying power.

Doing the Same Thing, Except Not REally

Up to this point, the Resident Evil franchise was known for its fixed cameras and tank style controls. Most seem to think that this method was a way of making the player feel like they have less than complete control. While, yeah, that style is certainly dated, I’m of the opinion that done right, it can still be effective in the modern day. That’s beside the point, though. RE4 did away with all that, instead shifting to a behind-the-shoulder perspective that was so simple it’s a wonder more games hadn’t done it before. 3D gaming in 2005 was still a relatively new thing, just a little over a decade old, and developers struggled to figure out their cameras sometimes (I admit that I used to have rose tinted glasses with this, but after having beaten Super Mario Sunshine on the Super Mario 3D All Stars collection, it’s shocking just how much developers struggled with cameras back in the early 2000s).

Capcom instead thought, “Let’s let the player see directly what’s in front of them.” Bam. Where Leon moves, you move. No more aiming at an enemy off screen, hoping you’re hitting them and not wasting precious bullets. Players could now aim their gun at different, specific body parts of enemies in the game, and they had a clear view of where they were looking. You might argue that this takes away a lot of the tension from the early installments, but Capcom thought of a way around that.

In the early titles, there was a huge emphasis on animations and timing. Even aiming your gun took a specific amount of time, meaning that every time you aim, it is a conscious decision on your part. You couldn’t aim at different body parts, and aiming too slowly could result in a zombie chowing down on whatever character you’re playing as. Aiming in Resident Evil 4 is rather quick, meaning that Leon will ready his weapon almost instantaneously. A very common complaint I’ve seen with the game, though, is the fact that you can’t move and aim at the same time (a problem they would soon rectify).

Phooey to that, I say. The fact that you can’t move and aim not only lends Leon a sense of vulnerability, but it also does the exact same thing that aiming in the old games did. Since you’re always up against some ungodly threat, the player must make a decision about when they’re safe enough to fire back at the enemy hordes. It’s still a conscious decision on the player’s part. Every shot you take still feels significant since you immediately make yourself vulnerable by aiming your gun. It might take some adjusting for someone who hasn’t played the game before and are used to more fluid gunplay in newer games, but the game is balanced around this fact. Enemies are slower than in other horror titles to compensate for Leon’s deliberate aiming, and they often have specific moments of vulnerability the player must exploit to exterminate them. It creates white knuckle tension that is still effective to this day.

REinventing the Wheel

Not only did Capcom entirely change the player’s perspective, but they threw out all of the established rules the series had gone with for its previous entries. The base enemies (called Ganados) are humans infected with an alien parasite, turning them hostile towards Leon Kennedy. Leon even comments “He’s not a zombie…” if you examine the corpse of the first enemy you come across. Instead, there’s an illusion that the threat Leon is up against is far more intelligent than the undead hordes of his sordid past (functionally, they’re not that intelligent outside of certain scripted sequences).

Gone, too, are the “messed up giant animal” bosses of the series’ past. In its place are immediately iconic sci-fi horror monstrosities like a gigantic fish with multiple tongues who lives in a nearby lake; a strange, almost insect-like body guard of the game’s middle-act villain; a dude with a giant sword for an arm; and—one of my personal favorites—a scorpion humanoid thing that has a giant jaw coming out of its back. Its insanely creative monster design in a series that has a few standouts but often falls back on “let’s make a real world animal kinda decayed.”

It all leads to a feeling of almost nonstop intensity. Even in the game’s quieter moments, it’s simply biding its time and letting the player ease into a comfortable routine before yanking the rug out from under them. And this creativity in creature design merges with the way the game is paced to make it feel wildly unpredictable. Though you start off in a small rural village, things escalate more and more as you go on, and each environment feels distinct from the last.

Take, for instance, the game’s iconic opening sequence. After Leon is attacked by the man he asked about the kidnapped President’s daughter, he travels down a woodland path with a few more enemies that mostly act as cannon fodder. Sure, the Las Plagas are unnerving, but don’t feel terribly threatening. You pick up some ammo along the way, maybe a few grenades, and most players might think “what do I need these for?” Then you reach the village proper, and you realize just how much Resident Evil 4 takes joy in messing with player expectations.

The player witnesses the villagers going about their daily life, moving hay, bringing things from one spot to another in wheelbarrows, but it’s all marred by the impaled corpse of a cop burning on a pyre smack in the middle of the village. It lets the player know that these enemies are not to be taken lightly, and if you wander into the middle of the village square, everyone will immediately start swarming you. And from here, it’s largely up to the player how this encounter plays out.

There’s a rather large house to the left that holds a shotgun, but going that way will spawn the game’s most iconic enemy Dr. Salvador, a dude with a bag over his head and a chainsaw in his hands. That chainsaw will kill you in one hit, but the shotgun is great for crowd control. Another option you have is running off to the right to a smaller house that has a metal door and almost no other entry points outside the front door. A nice idea in theory since it’s rather easy to barricade, but then you’re simply stuck with a pistol, and you are cornering yourself. If you run out of ammo, you’re basically SOL. Regardless of which option you pick, you feel like the odds are against you, that the developers are watching you squirm in a cage of torment, and just when you’ve run out of bullets, just when you think that this is it, you’ve already gotten a game over, you slay the last enemy needed to trigger the cut scene that ends the scenario, and you can breathe a sigh of relief while Leon cracks a God awful one liner about all the enemies going off to play Bingo.

This is immediately followed up by a few more relaxed areas, like a small farm which introduces the Blue Medal hunting side quest, and a pathway to a dead end house that sees Leon meet Luis Sera, a doctor who has gotten himself broiled up in the Las Plagas plot. Sure, there are enemies, but after the intensity of the opening, these areas are relatively tame, although by this point, the game has taught the player to remain on their guard at all times. This all leads in to the next big set piece, where the player must traverse a valley filled with enemies. It may not be as intense as the village, but it definitely gets the blood pumping.

And all of this is where the true strength of the game lies. As much as I love the combat, it truly is the pacing that makes this game a masterpiece. There are peaks and troughs all throughout the story mode, moments of nail biting, overwhelming tension, which is then alleviated by a slower paced, exploratory segment that lets the player regain their scruples, as well as explore the environment to replenish their ammo.

Not only that, but the variety in the set pieces is staggering. One sees you defending Ashley Graham while she works some switches that raise a bridge you need to progress while also fending off waves of enemies that come directly for Leon. Another sees players revisit the village from the game’s opening, only this time it’s during a rainy night and the player has been exposed to the Plagas that reside in the bodies of all the enemies they face. Perhaps my favorite one, though, sees the player get on some mine carts as they ride a literal roller coaster from hell. Enemies stop the cart from moving, and you must manage which enemies are in which cart. It’s a white knuckle sequence that never fails to invigorate me.

This absolutely razor’s edge pacing is the game’s greatest asset, and it helps the game feel fresh even on repeat playthroughs. A curious criticism I’ve seen is that the game’s third act, where Leon and Ashley go through a military base, goes on for way too long. I’m going to have to disagree—like many other parts of the game, it’s filled with highs and slower moments just like the rest of the game, and it ends with a grueling crawl through an enemy base before taking on the final boss. It truly feels like a culmination of everything that’s come before, a final push towards victory before the finale, and it still manages to be genuinely horrific and unsettling, namely with the Regenerators. These are enemies that, true to form, can regenerate lost limbs. They mumble creepily as they saunter towards Leon, and they always manage to send a shiver down my spine.

What was once a slow burn, horror themed experience was turned into a perfectly paced horror-action thrill ride. When you weren’t blasting away at hordes of enemies, you were soaking in the game’s atmosphere, which changed from act to act. The first third of the game feels like rural horror straight out of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the second invokes Gothic horror and creepy cults in a medieval castle (with the series’ best villain to boot in the form of Ramone Salazar), and the final third is a nice blend of all the horror and action elements that came before it. It was a hell of a reinvention of the series, and it remains a blast to play to this day.

What’RE ya Unlockin’?

Something that gives the game real legs is its generous helping of unlockables. Not only are there plenty of weapons to upgrade, with a nice variety in handguns, shotguns, magnums, and snipers, but there were plenty of bonus modes and unlockable weapons that gives the game a lot of replayability. For instance, upon beating the game, you unlock Matilda, a three round burst handgun that resembles Leon’s preferred firearm from Resident Evil 2. You can also unlock the Infinite Rocket Launcher, a weapon that’s basically, “I want to snipe this guy, but also want him to disintegrate in a fiery explosion.”

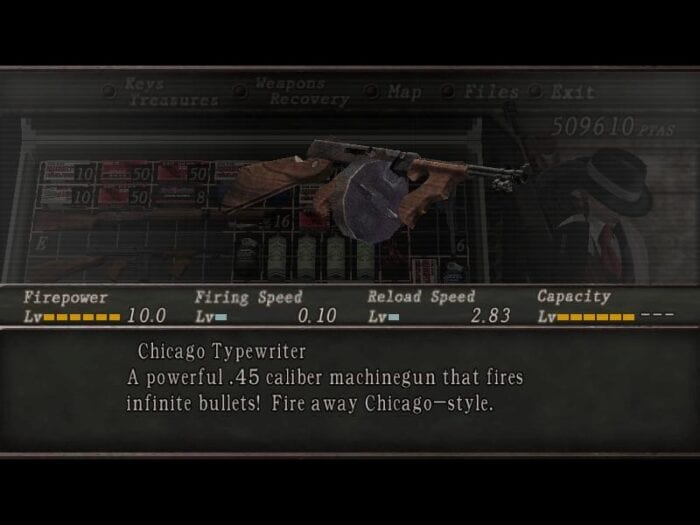

There are also some side scenario that, strangely enough, contradict each other depending on which version of the game you play. The original Nintendo Gamecube release simply has Assignment Ada, which sees players play as Ada Wong as she tries to retrieve the Las Plagas sample. Not only does she wear a different outfit from the main game, making its canonicity questionable at best, but the end fight against a resurrected Krauser really raises some eyebrows. But hey, it’s very reminiscent of the “Fourth Survivor” in that it’s an uber-tough gauntlet of enemies and resource management through some of the game’s later areas. It’s also designed to be beaten in one sitting, although it might take a few tries due to the sheer amount of enemies the game throws at you. Beating this mode will unlock the Chicago typewriter either for the main game, or another mode depending on which version you own.

Separate Ways is another campaign which shows what Ada was up to during Leon’s adventure. This one, weirdly enough, also concerns her ultimately getting the Las Plagas parasite, and I think it’s meant to be the canon one. On the one hand, it’s kind of cool assisting Leon in his opening siege on the village, and participating from the sidelines in major set pieces from the main story. On the other, it raises all kinds of questions. For instance, in the second to last chapter, Ada full on blows up two battleships that are in the military base, but this is never seen, heard, or mentioned in the main storyline. I’m sorry, but I’m calling BS on that. But, taken as an extra slice of gameplay, Separate Ways is an extremely enjoyable, and much harder, experience than the original game. Enemies hit harder, guns do less damage, but you get to play around with Ada’s abilities, like her grapple gun. And it gives you a weapon exclusive to her scenario in the form of a crossbow that explodes after a few seconds of being stuck in an enemy. It’s a literal blast, and a nice callback to the crossbows from previous entries. But like the main game, there are some exciting set pieces, and even a few cool new boss battles thrown into the mix. The cut scenes are weirdly really bad looking, but why are you playing a Resident Evil title for the story? Anyways, beating this mode unlocks the Chicago Typewriter for the main game, which is nice for subsequent playthroughs since it absolutely mows down anyone standing in your way.

There’s also a Hard Mode, which certainly lives up to its name. Like Separate Ways, enemies hit much harder, guns do less damage, ammo is rarer, and you can’t even buy the Assault Vest, an item which suits Leon up in riot gear and reduces the damage he takes from enemies. It really pushes the player to their limits, and challenges their knowledge of the main story. Even for someone like me, whose playthroughs of the game is now in the double digits, this is a really tough mode, but the reward you get is the PRL, a “kill that thing” button that can decimate almost any enemy, including bosses, in one shot. It’s a nice way to reward the player for struggling through the toughest mode in the game.

Suffice it to say, folks, Resident Evil 4 is exemplary when it comes to unlockable content. The special weapons are a lot of fun to play around with, even if they do trivialize the game’s difficulty. But the bonus story modes and unlockable weapons mean this game is good for at least three play throughs, unless you’re like me and simply can’t get enough of it. Of course, there is one more gameplay mode I’d like to talk about…

Guns for HiRE

Upon beating the main game, you can access The Mercenaries, a returning mode that functions as a way for players to test the limits of their combat skills. There are four maps to choose from, three of which are modified environments from the story (there’s the village from the game’s opening, the first area of the castle, and the military base from the segment where Leon gets helicopter support), as well as a whole new area called Water World, which has some interesting verticality to it.

Folks, The Mercenaries in this fourth installment ranks high among my all-time favorite bonus game modes from anything I’ve ever played. For one thing, there’s huge incentive to replay it thanks to the unlockable characters. You start off with Leon, who has a simple handgun and shotgun, but can eventually unlock Ada Wong, who rocks the TMP and semi-auto rifle; Krauser, who has a bow that deals devastating damage, a kick that can completely decapitate enemies, and the ability to periodically transform his arm into a sword and completely wipe out anything standing in front of him with a charge attack; HUNK, the guy from the 4th Survivor campaign from Resident Evil 2 who can control crows with his custom TMP, large grenade pool, and the ability to snap necks; and finally, you can unlock Wesker, who comes with a silenced handgun, a magnum, a sniper rifle, every type of grenade in the game, a punch that sends enemies flying, and the classically cheesy “I wear my sunglasses at night” attitude he’s so beloved for.

Of course there’s an incentive for getting a five star score on every stage with every character. Doing so unlocks the Handcannon, a stupidly powerful magnum which can eventually be upgraded to have infinite ammo. It’s a lovely throwback to Barry’s comical revolver (“I have this!”) from the first game, but honestly, playing this mode is, for me, its own reward. I’ve long since gotten five stars on every map with every character, but the fact that it offers such addictive, bite sized chunks of RE4 combat makes it very difficult for me to put down.

That’s not to say getting five stars on each map is easy. There are typically different kinds of special enemies on each map you must contend with, such as the chainsaw wielding Bella Sisters on the village map, or the Gatling Gun wielding JJ on the military base map. You must learn the intricacies of each character’s loadout in order to come out the other side a winner. For instance, you might be tempted to go for headshots with Wesker since he can do the aforementioned cool punch when enemies flinch. But you quickly find that the most common ammo pickup for him is Rifle ammo, meaning it’s best to find a nice, secluded spot and taking out enemies one by one by using the rifle’s high firepower.

The game rewards players for exploring the maps as well. You’re on a time limit, but that can be increased via pickups that are scattered around. It encourages players to be always on the move, and take advantage of every single facet of the game’s combat in order to keep a combo going. It’s a positively intense, wild side mode, and one that eventually turned into a full game with Resident Evil: The Mercenaries 3D. The game got middling reviews, but I have a feeling it would have me hooked for a good long while considering the frequency that I return to the mode in RE4.

And, as a side note, my favorite character is undeniably Krauser. I’ve seen people online say that other characters are better, and while that may be true, I find his powerhouse approach to perfectly suit my playstyle. He’s all about precision, killing enemies in just one or two hits. His bow can be tricky to use since it has such a slow fire rate, but it does a ton of damage when you do land a hit, making him a “high risk, high reward” type of character. Plus, the fact that he can kill anything in one hit with his sword arm, and that the hitbox for that move is stupidly broken, means that he’s arguably the easiest character to rack up a high combo with.

The REally Important Lessons Nobody Learned

RE4 was arguably the first entry in the linear action game genre that went on to define the late 2000s/early 2010s. And while the game is certainly linear, with the aforementioned set pieces being its crowning achievement, it never once loses sight of the fact that it’s a game first and foremost. But perhaps the biggest plague it delivered upon the world was its quick time events. I won’t say that it was the first game to ever have them, but it was the first one people paid attention to, and for some reason, imitated to death.

Resident Evil 4 introduced the idea of contextual button presses in the middle of cut scenes in order for the player to avoid a game over. There are numerous segments where the player must hit the button combination that flashes on screen, the earliest of which is when Leon does his best Indiana Jones impression by outrunning and dodging a boulder (perhaps a call back to the late game boulder dodging in the original Resident Evil). If the player misses the button press at the end of the run, they’re run over by the boulder. Succeed and…they live to fight another day.

I’m not going to bury my thoughts here: the QTEs in Resident Evil 4 have not aged well whatsoever. They stuck out like a sore thumb even during the game’s initial release, acting as a small pox upon an otherwise pristine product. The idea was to merge the cut scenes with gameplay, but the end result was something that felt largely token and thrown in as an afterthought. In hindsight, the QTEs don’t really add much to the game, apart from checking that you’re paying attention during the cut scenes.

And yet, there were a whole host of games that adopted the idea following RE4’s immense popularity. Suddenly, every major release had QTEs that were meant to immerse the player in the world, but in actuality only serve as arbitrary roadblocks to progression. This does, of course, open up the larger can of worms when it comes to RE4’s influence on the gaming industry; everyone sought to imitate it, but no one understood what made the game great.

RE4 is undeniably a linear game, but it still offers players a lot of choice in how they tackle objectives thanks to the flexible loadout building and weapon upgrading. One player might tackle the opening village segment by going on one house, while another might go in a totally different direction to survive. Both are equally viable options, and the end-game loadout might vary from player to player as well. Both rifles, for instance, are radically different. The original bolt action has much more damage per shot, but a slower fire rate than the semi-automatic, which sacrifices some power for a much faster firing rate. Some people might fully upgrade the Grenade Launcher so it homes in on enemies, while others may not even touch the thing. Despite the fact that the set pieces mean every player will have the same general experience, there is still room for customization and fine tuning your loadout.

But RE4 showed the world that you can achieve movie-level bombast in a video game, and it ushered in an era of linear action games that take choice away from the player. I’ll fully admit that this is my own personal bias creeping in, but the late 2000s/early 2010s were plagued by games that looked really nice but didn’t offer much in the way of complex, engaging gameplay. Suddenly, every game had you looking over your character’s shoulder and blasting away at enemies with slight variations on the formulas established by RE4. Series like Uncharted and Gears of War launched into platinum-best selling status, but they took away the control from the player in some crucial ways, especially as the series went on. Suddenly, set pieces could determine whether or not you even keep your weapon, as is the case in the entire Uncharted franchise. As I’ve grown older, I’ve come to like this style of game less and less. Sure, there’s fun to be had in the sheer spectacle of their set pieces, but the really engaging parts of RE4, where you determine your weapon loadout or how you approach a situation, is mostly taken away from the player. It frustrates me to no end when a game completely strips the player of whatever weapon or ability they had for the sake of the story. It was an era of games that was all spectacle and just a slight amount of substance, although there were exceptions like Spec Ops: The Line.

And even though RE4 is an amazing game, it even set an uncomfortable trend within its own franchise. The following installment was hardly scary, although quite enjoyable from a gameplay perspective if you had a second player (The Mercenaries was further fleshed out, as well, and was addictive as all hell). RE5 largely tried to ape the best parts of RE4, but stripped out much of the intensity and edge-of-your-seat survival elements that made its predecessor so good. This tendency towards spectacle over subtlety culminated in the sixth main entry, as well as a host of spinoffs like Operation Raccoon City that are considered some of the lowest points in the series by anyone whose played them. RE4 is, by itself, a great game, but it steered the series in a direction that was less than desirable by most longtime fans of the series.

I can only think of a few games that tried to ape the success of RE4 and actually succeeded, and the one that stands tall in my mind is Dead Space 2. While I think that franchise as a whole doesn’t know the meaning of the word subtlety, the second entry is the closest most other games have come to capturing the white-knuckle thrill ride that is Resident Evil 4. Not only do you have a rather extensive arsenal of weapons to choose from, ranging from assault rifles to gravity-based chainsaws, but it, too, constantly mixes things up. One moment you might be creeping through a freaky nursery filled with exploding babies, the next you might be fighting enemies that will hide and stalk you. And, like RE4, the flexibility and sheer enjoyment of using the game’s weapons allows room for players to choose how they tackle a given objective. There’s always a right time for a particular weapon, and this player choice mixes with the sheer visceral thrill of some of the wild stuff it puts players through.

Resident Evil 4 in REview

What does all of this add up to? Why does RE4 still matter? The answer to the former is that the end result of Capcom’s reinvention of a beloved series is an all-time great horror shooter that still manages to feel fresh and fun thanks to its marriage of mechanics with big set pieces. The answer to the latter is a bit more complicated.

Resident Evil 4 is indicative of what happens when someone has a really good idea (or set of ideas) and manages to execute their vision to its fullest extent. Given the hardware limitations of the time, it’s remarkable how subsequent HD rereleases have managed to make RE4 still feel relevant in the current gaming landscape. The game came to define some of the biggest releases of the following decade or so, but so few of them even came close to capturing what makes RE4 so goddamn good. Sure, its story is total nonsense and doesn’t stand up to even the slightest scrutiny, but none of that matters because, at the end of the day, RE4 is a game first and foremost, and it hides depth within its penchant for gory spectacle.

It’s also indicative of the Resident Evil series’ ability to reinvent itself. RE4 is so different from everything that came before, but it still feels like it belongs in the franchise, even when you ignore the subsequent entries. It set the precedent for one of gaming’s biggest horror franchises, and the effects of its innovation are still being felt in games today.

Maybe now, at the end of this lengthy article, is the time to admit something: Resident Evil 4 is my most replayed game of all time. It’s not my favorite game ever made, but it is the one I have replayed the most, with, as I mentioned earlier, my playthroughs easily numbering well past 25 at this point in my life. It was, for a very long time, a game I replayed at least once a year, if not more, and the addictive nature of The Mercenaries keeps me coming back for more when I have a hankering for the specific type of action it offers.

When all is said and done, friends, Resident Evil 4 is a gaming masterpiece, a shining example of the level of engagement developers can give players. And even though a remake is almost inevitable at this point, the original stands tall even 15 years after its initial release as a masterful example of creative game design. And no amount of boulder punching in the following entries in its own series can change that.