My brother introduced me to the horror fiction podcast Welcome to Night Vale probably around 2013 or 2014, so roughly a year or two into its run (the show premiered in June of 2012). He did so without telling me that it was fiction, so I had no context for what I was listening to, instead thinking that it was some sort of elaborate hoax. It’s hard to describe Welcome to Night Vale. It certainly isn’t a pure horror story, with equal parts black comedy and absurdism present [1]. The opening lines of the first episode may best and most succinctly capture the essence of the now beloved podcast: “a friendly desert community where the sun is hot, the moon is beautiful, and mysterious lights pass overhead while we all pretend to sleep.” These lines set the stage for so much that would come after it: a story that is rooted in its townspeople’s humanity, but also in the existentialist extradimensional magical realist Lovecraftian dystopian horror that the townspeople have to deal with—or at the very least pretend they don’t notice—every day.

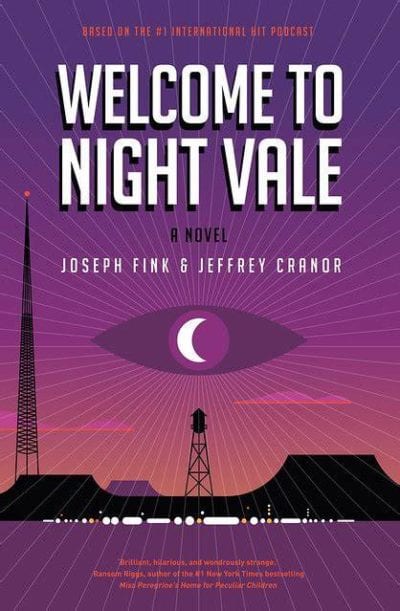

Welcome to Night Vale unfolds like a bizarre found footage relic from another dimension. Created and written by Joseph Fink and Jeffrey Cranor, the podcast takes the guise of a community radio show. The show’s host, Cecil Palmer (voiced by actor Cecil Baldwin) relates the goings-on around the fictional desert town of Night Vale. There is a slate of recurring segments that you would find on most radio shows—ad reads, traffic reports, community calendar, and weather reports are the most common—however, these segments, especially traffic and weather, only rarely convey what they’re supposed to. Most famously, the weather segments are full-length musical interludes by independent bands and artists.

A quick aside before we get too far: I’ve always thought that it’s strange that the show credits Baldwin’s character as “The Voice of Night Vale,” while crediting other actors as “the voice of [character name].” Describing someone as the voice of something is a common practice in radio and announcing, but it strikes me as odd that it’s how they credit a named character. The likely answer is that Fink and Cranor didn’t come up with a name for a few episodes and decided to keep the credits consistent, but since fan theories are much more fun, I’ve come up with a better explanation. For a little while, I thought that Cecil might be a disembodied voice speaking out over the radio, but there’s been too much evidence over the years of him having a corporeal form.

Instead, I think that he could be the literal embodiment of Night Vale—the spirit of the town in human form. Cecil reflects the best of Night Vale’s humanity, he’s friendly, loyal, and mostly kind (he has weird grudges, most notably against his brother-in-law Steve Carlsberg and local community theater director Susan Willman, who just seem to rub him the wrong way), but also potentially immortal and inhuman. Given that stranger things happen in Night Vale on a daily basis, it seems wholly possible that the town, which already seems to have a personality of its own, might take a human form. Cecil, as “The Voice of Night Vale,” would be the perfect candidate for such a personification.

The more disparate segments in each episode are typically tied together with an overarching plot. This is even true in the earlier episodes, which I usually consider to have much more independent news stories and segments. In the first episode, the overarching plot is the arrival of a scientist named Carlos, who thinks Night Vale is “by far, the most scientifically interesting community in the U.S.” An understatement, to say the least.

Fink and Cranor often develop the various news vignettes and plots into larger, sometimes year-spanning storylines. When I revisited the first episode for this essay, I was struck that almost the entire episode—the new dog park that no one is allowed into, the encounter with a cadre of angels by Old Woman Josie, the arrival of Carlos, the disappearance of an airliner that mysteriously appears in an elementary school gymnasium, the man of Slavic origin inappropriately wearing a headdress, and the underground city underneath the Desert Flower Bowling Alley and Arcade Fun Complex—spawned several major story arcs.

The show’s style has evolved through the years, with Cecil taking a decidedly more conversational and personal tone than in early episodes, which featured a much more straightforward news delivery. The format has become a little bit looser, often resembling long-form monologues instead of community radio reports. It’s now much more common for him to stray from the news in favor of more personal anecdotes. Part of this shift can be attributed to Fink and Cranor’s desire to use the show as an outlet for experimentation, like in “A Story About You” (Episode 14), which is almost exclusively told using second-person perspective, “Go to the Mirror” (Episode 171), which only uses questions, and “All Right” (Episode 94), which only plays sound through the right audio channel. Fink has also been open about using random number generators for story inspiration.

Despite the recurrence of numerous structural elements across the show’s episodes, Fink and Cranor’s commitment to experimentation make it hard to ever call Night Vale formulaic. Repetition across long stretches of episodes allows the audience to recognize the “rules” that Fink and Cranor are operating under. In an episode about rules and games of their creative writing podcast, Start With This, Fink says:

If you tell the audience the rules, or make it apparent to the audience, then we know where we’re going and we know what the stakes are. We see the skeleton. And that allows you to take the art in all sorts of directions that maybe the audience would feel unsure about, or an audience might be like ‘I don’t know where you’re going with this.’ But if you’re like, ‘this is the rules of the game,’ then they’ll go with you kind of anywhere as long as you’re still following those rules. It has this built-in excitement and fun and tension for the audience when you’re playing a game and they know the rules.

Whether intentionally or not, Fink and Cranor have set up rules for the podcast: Cecil always introduces the weather, the weather is always a song, “The Ballad of Fiedler and Mundt” by Disparition always plays under the cold open, traffic reports are always actually haunting meditations, etc. But Fink and Cranor also know when to break their rules, and the effects are often jarring and disorienting—which is, of course, exactly what the writers want.

Even with the bizarre horror pervading the town of Night Vale, there is a strong and often deeply moving emotional core and humanity present in the stories. The audience’s willingness to follow Fink and Cranor allows for them to also use incredibly rich and evocative prose that they might not be able to otherwise. The expectation that the prose might be different than the audience is used to is set from the cold opens, when Cecil typically intones an especially cryptic or discomforting line. The audience is then prepared for much more poetic passages during the rest of the episode, like this one from “The Promise of Time” (Episode 157):

You see, when we deny death and toss ourselves into the future, we do so with the strange delusion that the future feels it owes us life. That in the world of the future they would want nothing more than to devote time and money into resurrecting each of us into eternal wellness. But the future does not feel any obligation to us at all. The past means only one thing to the future: the past is a resource.

The audience is also treated to rich characters that constantly defy their expectations. Some of the most eloquent lines are reserved for (who we are led to believe are) its most ineloquent characters, like Steve Carlsberg, who reaches incredible depths when talking about his brother-in-law Cecil and the oddity of the town. Another standout character, The Faceless Old Woman Who Secretly Lives In Your Home (Mara Wilson), never fails to nonchalantly and mesmerizingly describe how she ruins people’s lives.

In a year that is (hopefully) as close to the world of Welcome to Night Vale as the real world will ever get, the podcast’s richness and heart provide an unexpected respite. The incredible humanity and resilience displayed by the citizens of Night Vale, even in the most extreme circumstances face of sentient glow clouds, interdimensional sandstorms, literal five-headed dragons, and omniscient obelisks, all while living in a dystopia controlled by a “vague, yet menacing, government agency,” is much more cathartic than you would think they would be in the waning days of 2020.

[1] Although, maybe we should consider the Faceless Old Woman’s words: “There’s a thin line separating humor and horror.” Joseph Fink and Jeffrey Cranor, The Faceless Old Woman Who Secretly Lives in Your Home: A Welcome to Night Vale Novel (New York: Harper Perennial, 2020), 145.