In Salem, Massachusetts 1692, the witch trials started. Women were accused of being in league with the devil for countless reasons. The public took to outrage, and no one could trust their neighbor anymore. The world of the 17th century Salem citizen was one of sheer panic and terror. And of course, it was all just bullsh*t.

The first three women to go on trial would never have a fair shake explaining their actions in a courtroom. If something didn’t fit into the Christian belief system of the time, it was immediately considered a heresy. Subsequently, the three would face execution for witchcraft. After this became the standard, powerful people would use it to manipulate the system. If a woman owned land they wanted, she was a witch. If a woman they lusted for was with someone else, then obviously the woman had cast a spell over them. You can see where this is going.

It’s only fitting that the documentary The Witches of Hollywood have its world premiere at Salem Horror Fest. There isn’t a more appropriate place in the world to premiere a movie like this. The film paints a picture of misogynistic control through the depiction of the stories of the women portraying a witch.

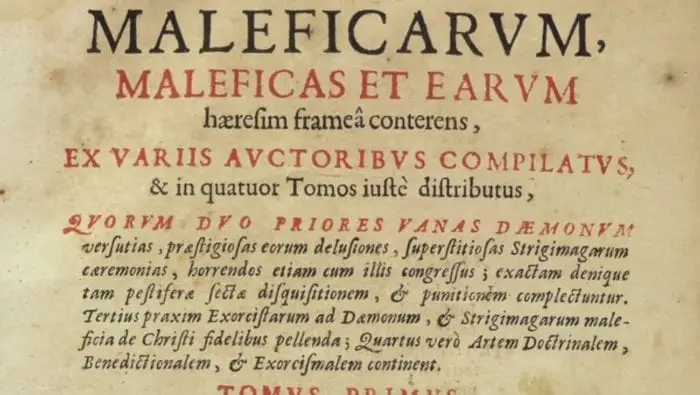

The film starts by introducing viewers to the Malleus Maleficarum, the manual written in 1486 by a German clergyman in order to fight the devil. The title translates to Hammer of Witches. The book was sparked by the Spanish Inquisition in 1478, and it incurred the death of eleven people in Spain and thousands more across Europe through the next two centuries. It was a real catalyst of power for the Catholic church, and the men within its ranks, to command.

The Witches of Hollywood stays in the bounds of films any person from the last couple of generations would have seen. Starting with ideas of jealousy and lustfulness in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, revered authors and scholars Peg Aloi, Heather Green, Pam Grossman, Danica London, and Kristen Sollee expand on the vilification of witches. Through the last century of film, Sophie Peyrard shows us how things are finally beginning to change.

The audience is made aware early on that women were not writing these prodigious Hollywood scripts. And just as the Catholic church and Salem residents would subvert their neighbors, Hollywood undermines women in a similar fashion. The film singles out ladies from two films in particular. Veronica Lake in I Married a Witch and Kim Novak in Bell, Book, and Candle. Both iconic romances are also allegories for women with power willing to concede to societal standards.

The Witches of Hollywood does a fantastic job of creating a timeline for these films and moving through the years watching temperance toward witches shift in society. The Bell, Book and Candle portion wonderfully explains the societal narrative of the year it released, with WWII soldiers returning home expecting their women to do the same, and movie productions being swayed toward mending frail male egos and convincing women to give up their independence and settle into the life of a housewife.

Working itself up to modern era witches, the documentary highlights The Witches of Eastwick, The Craft, and The Chilling Tales of Sabrina. I do think the film misses some attempts to connect the oppression of feminism with witchcraft, leaving out many things I would have loved to have seen conversations on. Many of the early silent film portrayals don’t even receive mention. Dreyer’s 1929 art film The Passion of Joan of Arc for starters. The cinematic triumph was subjugated and recut by the French government and the church. But then again, I suppose that’s off-topic given that these are The Witches of Hollywood.

I also would enjoy having seen more information regarding the effect on films from the McCarthyism era. The 1950s “witch-hunt” led by Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy led to the blacklisting of many screenwriters, directors, and various other entertainment professionals. With McCarthyism, Hollywood saw an intolerant man vilify many innocent people, many of them homosexuals. The Witches of Hollywood stays on topic, concentrating its efforts solely on female subversion. It does make mention of the satanic panic in the ’80s, but McCarthyism may not have fallen into the movie’s focus. This film results in being more about creating witches in Hollywood rather than casting them out.

Then I thought it may be missing something in not venturing out into topics of voodoo or hoodooism in films. Witchcraft looks mighty different when it’s Creole spirituality. I thought maybe we would see some Serpent and the Rainbow, Sugar Hill, or The Skeleton Key. Though the practices are similar and wildly misunderstood in our culture, the film stays on topic by focusing on witchcraft.

There are many witches the film is missing, so don’t expect to see all your favorites. But I suspect it has to do with what studios might have been willing to participate in. Angelica Houston’s marvelous portrayal in The Witches is certainly missing here. Especially as the film begins talking about women finding power through their ability. But as far as the approach the film takes in dealing with domicile subversion, Houston’s witch wouldn’t fit.

I obviously came into this film wanting a lot, but the fact is The Witches of Hollywood gets everything right. From my perspective, my curiosity to want the film to venture out a little further should speak volumes. At only 55 minutes The Witches of Hollywood does what any good film should: it sticks to its guns and leaves its audience wanting more.

The film paints a vivid portrait of gender suppression. I hold a great appreciation for documentaries using movies to help make their point without going off the rails. As a reviewer, I can talk about movies all day. Overall, the topic is genuinely engaging. My only real criticism lies somewhere between loving what the film has put together and finding it limiting. The film works as a well-framed snapshot of a niche topic instead of filling a larger canvas. To conclude, The Witches of Hollywood is still a spellbinding watch.

The Witches of Hollywood will have its world premiere at this year’s all-virtual Salem Horror Fest 2020 during its second weekend on October 9th. An all-access pass will allow you to see all the films, panels, retrospectives, and more that begin showing on October 2nd.

Lots of mistakes in this one. The article claims the “Malleus Maleficarum” (written in 1486) sparked the Spanish Inquisition in 1478 – several years BEFORE the book was written (time travel?) and in any event historians have pointed out (including Neo-Pagan historians such as Jenny Gibbons) that the Malleus was condemned by the Catholic Church shortly after publication and placed on the Index of Forbidden Works. The Spanish Inquisition used the “Directorium Inquisitorum” if I’m not mistaken. Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc” wasn’t recut by either the French government nor the Church: the first version was lost in a studio fire and Dreyer remade it himself, then it was lost for many years before being found in a closet.

Thanks! I talked with Sean about this and we’ve made a change to the wording. Apparently he meant to say that the Malleus Maleficarum was sparked by the Inquisition, not the other way around. I should have caught that, frankly, so mea culpa. This also undercuts the implication that the Church was cool with the Malleus Maleficarum. Of course you could still dispute the claim. Cursory research seems to indicate that there were indeed pressures from the government and church that led to cuts when it comes to Dreyer’s film, but that Dreyer’s version was discovered 1981. So I’m leaving that for you two, and/or others, to debate if so inclined.

I have also added a couple of links to the text at Sean’s request