In a previous article discussing the horror cinema of the 1960s, I referred to Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) as the two most important horror films of the decade, as well as the two films most instrumental in the shift from classic to modern cinematic horror. Over the course of two articles, I would like to explore each of these films in a bit more depth than the survey format of my previous article allowed for. This week: Psycho.

Hitch Gets Unseemly

To some, it may seem odd to describe a black and white film from 1960 as integral to the transition from classic to modern horror. Psycho is, of course, now firmly entrenched as not only a classic of the genre, but of cinema. Furthermore, to some contemporary viewers, it may not seem particularly modern. However, at the time of its release, it was quite modern, even scandalously so. Things we take for granted now, like a post-coital conversation in a hotel room between a partially undressed, unmarried couple, was anything but commonplace in 1960. For the time, this was a startlingly frank depiction of what would have been considered pretty unsavory material. And this is how the film starts, before we get to the truly shocking and horrific stuff.

Thus, Psycho was a film that, for many, lacked a certain decorum that was expected of films generally and of Hitchcock in particular. This likely explains the decidedly mixed critical response to the film at the time, with reactions ranging from bemusement to slight distaste to outright indignation. The consensus seemed to be that this was one Hitchcock film not destined for classic status. This isn’t that surprising as Psycho was a somewhat radical departure for Hitchcock. Though it certainly shared some common stylistic and thematic traits, it was unlike anything he had previously done. As a result, Psycho took many filmgoers by surprise (and for some, the surprise was less than pleasant). Given the film’s now-legendary status, it’s amusing to read some of the unfavorable reviews from the time. Here’s one (which I can only describe as “beastly”) in which an eminently respectable critic from an eminently respectable publication bemoans Psycho’s eminent lack of respectability.

No doubt, many viewers were thrilled by Psycho’s potent mix of mundanity, abnormal psychology, and shocking violence (violence which felt aimed nearly as much at the audience as at the characters onscreen). For others, though, it was all just a bit much: a bit too much transgression, a bit too much subversion, and a bit too much nihilism. Psycho was darker and bleaker than anything Hitchcock had done previously, though as noted, there had been traces of the macabre in much of his previous work. It was also undoubtedly ahead of its time, and it was not until later in the decade (and into the following one), that horror films with a similarly confrontational tone and style would become the norm rather than the exception. This coincided, of course, with a state of national and global affairs that seemed only to go from bad to worse. In a way, looking back at Psycho, it seems not only a sign of what was to come in cinematic horror’s near future, but also an early portent of the increasingly grim trajectory of the decade itself.

The 1960s: The 1950s, Part II (?)

On that note, it’s interesting that Psycho came out at the very start of the 1960s. Much of the exuberance, triumphalism, and general sense of optimism that characterized the US in the 1950s was carried over into the new decade. It is, of course, an oversimplification to paint the early years of the 1960s as some kind of carefree paradise in which Americans were simply too enamored of the Kennedys and Camelot to worry about trivial things like Soviet missiles 90 miles off the coast of Florida. However, when one considers the direction the decade would take, with the violent punctuation mark that was JFK’s assassination bringing the early 60s to an abrupt end, followed by increasing turmoil and strife for the rest of the decade in the form of the antiwar movement, race riots, and more assassinations, it’s hard not to see the early years of the decade as a kind of honeymoon period or a calm before the storm.

Certainly, Psycho would still have had an impact even if it had come out later in the decade; however, let us put the fact that it came out in 1960 into perspective. This is before JFK’s assassination; before the escalation of the war in Vietnam (before most Americans even knew where Vietnam was, let alone watched nightly news coverage of the war); before the widespread demonstrations and civil unrest that would come to define the decade (the television news coverage of which, like that of the war in Vietnam, would bring shocking real-life violence directly into people’s living rooms); before (just barely) Americans would see their first images of the Nazi concentration camps in LIFE magazine; and before the Bay of Pigs fiasco and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

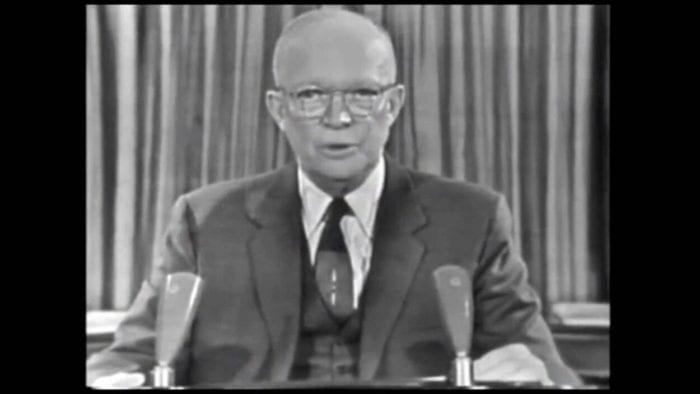

In 1960, Ike was still in the White House (and had not yet warned us about the military-industrial complex) and the nation was on the verge of electing (albeit in closely contested, even controversial fashion) a charismatic, young president that would galvanize large segments of the population to reach for the stars, both literally and figuratively.

Moving away from the sociopolitical side of things, it is as revealing, if not more so, to look at the cultural landscape as it was in 1960. At the risk of generalizing, it’s fair to say that the US in 1960 was still fairly buttoned-down, yet another holdover from the previous decade, one in which everything was hunky-dory and peachy keen (and if it wasn’t, you were still supposed to act like it was). To use popular culture to further illustrate the point, consider the following: 1960 wasn’t just pre-Summer of Love and Woodstock, it was pre-The Beatles and the British Invasion. Elvis, pre-sequin jumpsuits and sideburns, was still the tops; so, for that matter, was Sinatra. The highest-grossing film was Spartacus; the best-selling album was The Sound of Music soundtrack, and the most popular TV show was Gunsmoke.

Marijuana was something most people were, at best, vaguely familiar with (chances were, you had never used it and, furthermore, you probably didn’t know anyone who had either). A bad trip was a vacation where it rained the whole time. Long hair on men was almost unheard of (even in 1964, pre-psychedelics and still wearing suits and ties, The Beatles, with their modest mop-tops, were considered “longhairs” by many).

With regard to sports, figures like “Broadway” Joe Namath, he of the bold promises, fur coats, and oozing sexuality, were several years away. 1960 was solidly the era of players like Johnny Unitas, he of the good, old-fashioned sportsmanship, varsity jackets, and in the words of Abe Simpson, “a haircut you could set your watch to.”

All of this to say that the sociopolitical climate (standard Cold War caution tempered by an abundance of optimism about the future) and cultural landscape (rock ‘n’ roll balanced by a generous dose of staid conservatism) of the US in 1960 was drastically different than what they would become as the decade went on. This is the milieu into which Psycho enters upon its release; Psycho, with all its sordid nastiness (thematic and aesthetic), must have been like a crazy person who walks into a nice, catered brunch and wipes their sh*t-covered boots on the carpet.

Forgive Us Our Trespasses

For 1960, and for a Hollywood film with known stars and an even bigger star behind the camera, Psycho is more than a little transgressive. Psycho is a film in which numerous boundaries are either crossed or blurred, at times to the point of near nonexistence. While it is chiefly through the character of Norman Bates that transgression is enacted, the film itself has something of the transgressive about it. For example, one of the boundaries that Norman, in his psychosis, no longer respects is that of public vs private; his character is defined as much by his voyeurism as by his murderousness. So too is the film defined by its voyeurism, not only in the lead-up to the famous shower scene, but from the very beginning of the film as well, when we are taken by the movement of the camera right into Marion and Sam’s hotel room and become privy to what should be a rather private moment (becoming essentially “a fly on the wall”, appropriately enough). Thus, from the onset, we have a film that implicates us in its voyeurism. First, through the omniscient, objective view the opening scene affords us, and later by the individual, subjective gaze of Norman.

However, the intrusion of the public view into private space is not the only transgression on display in the film. Even characters other than Norman Bates, including the film’s initial, would-be protagonist Marion Crane, might be considered transgressive, albeit in less extreme ways. Although technically not adultery because Sam is divorced, the relationship between he and Marion would have been considered illicit at the time, hence their clandestine meet-up from the film’s opening. Even the fact that Sam is divorced is itself transgressive, based on the social mores of the time. Of the two, it is of course Marion, by virtue of being a woman in 1960, who is the most overtly transgressive, particularly in her unmitigated desire (and her willingness to act on that desire). In 1960, the idea of a woman pursuing both sexual pleasure and financial gain outside the confines of marriage (and, in one case, outside the bounds of the law) was considered not merely unusual, but abnormal (and certainly a subversion of gender expectations, especially for a film in 1960).

As the transgressive center of the film, Norman Bates consistently disregards fundamental boundaries, including some on which our very society is based. Most obvious is, of course, his flouting of the taboo against murder. While bad enough in its own right, it is not the most disturbing transgression embodied by Norman, if only because, even in 1960, audiences were used to killers in their films. However, it should be noted that Marion’s murder was far from your garden variety cinematic murder in 1960, not merely for its stylistic ingenuity but also for the fact that it is highly sexually charged. While we, as the audience, obviously don’t see any actual nudity, we understand that the victim is a naked woman, we know that Norman has watched her undressing, and even before we know the identity of the murderer, we realize that the assailant, whoever it is, sees her naked body, even if we do not. If there were any doubt for first-time viewers whether sexual desire and repression were at the root of the killer’s actions, it surely should have been dispelled once it is revealed that it is Norman and not his mother.

Perhaps even more unnerving, however, is the transgression represented by Norman’s identity crisis, the state of subjective instability in which he exists and in which the border between self and the other is either blurred, in flux, or altogether nonexistent. I believe it is this, more than anything related specifically to gender confusion, that still has the power to get under the skin even of modern audiences. The desire or compulsion of an individual to become another person (not to become another gender, but to become another person; to subsume, or be subsumed by, the self of another) is inherently disturbing because it is unnatural. In Psycho, of course, Norman does not merely desire this loss of selfhood, he achieves it. Even without adding murder to the mix, we are inclined to see the resulting perversion of subjectivity as monstrous.

Finally, Norman is guilty of disregarding the boundary between life and death; not, in this case, the taboo against taking life, but rather the sacred distinction between living and dead. While belief in the life of the spirit after death is, of course, widespread, nearly all cultures accept the finality of physical death, that the body without a soul is no longer a subject but an object. It is for this reason that the idea of human taxidermy is repulsive, and why many people find even animal taxidermy unsettling. At the same time, even as we accept corpses as shells emptied of their essential humanity, and even among those who doubt or disbelieve the existence of the spirit after death, there is an almost instinctive recognition of the, if not sacred then at least “special” status of human remains.

Thus, while we do not accept the preservation of a corpse for display as natural, neither do we tolerate treating the bodies of the deceased like garbage to be burned in piles (or stuffed in car trunks and submerged in swamps). Both strike us as somehow unnatural and offend our sensibilities as civilized human beings. Therefore, Norman’s digging up of his mother’s body, subsequently attempting to preserve it, and treating it as if it were still a living being (dressing it, putting it to bed, talking to it) is deeply disturbing. Interestingly, all of this is the inverse of Marion’s murder and the subsequent disposal of her body, in which the living being is reduced to a nonliving thing. While we as the audience are, no doubt, meant to see these behaviors as aberrant, such a brazen depiction of such deeply transgressive behaviors (once again, in a major studio film in 1960) was a bold and shocking move.

Alfred Hitchcock: One of Them Subversive Types

As is so often the case, transgression and subversion go hand in hand in Psycho. As boundaries are transgressed, so too are rules, norms, and expectations subverted. With regard to subversion, Psycho is a film that, much like another film I have written about here, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (appropriately enough, given the influence of Psycho on that film), subverts at both the formal and thematic levels.

Most significantly formally speaking, the film subverts our expectations by removing the protagonist partway through the narrative. Up until her murder, Marion is clearly the film’s protagonist and the character with whom we are meant, consciously or not, to identify. It is her actions that drive the plot forward; furthermore, it is through her character that we feel a connection to the story. Once her character is removed from the narrative, the only viable substitute is Norman, the only other character whom we have actually gotten to know. We will, in fact, end up spending the majority of the film with him as his character becomes the focal point.

Notably, neither Sam nor Lila are viable replacements for the simple fact that we are never given enough about them as characters for them to feasibly serve as audience surrogates, which I believe is intentional. Had either of these characters been more fleshed out, they easily could have taken Marion’s place at the center of the narrative. In fact, this would have been the more typical approach. Instead, Hitchcock (and the screenwriter Joseph Stefano) choose to make Norman the only other truly significant character, forcing us to identify with him, whether we want to or not.

Thematically, the film is at its most subversive when it comes to our common beliefs about the salutary nature of mother-son relationships and about the power of redemption (specifically, that we may, through our own conscious, moral decision-making, effect a positive change in our lives). As to the first, rather than a postcard of wholesomeness (what is “Mom, baseball and apple pie” without Mom?) and well-adjusted-ness, the mother-son relationship in Psycho is a crime scene photo of the overbearing mother and pathologically devoted son dynamic taken to its most morbid extremes.

With regard to the latter, it is right at the point at which our protagonist has made the decision to “do the right thing” by returning the stolen money that she is brutally killed. The would-be redemptive power of her decision is unsubtly and quite intentionally signaled by both her white bra (it was black at the beginning of the film) and her choice to take a shower (she is going to get clean before coming clean). However, her symbolically purifying shower is interrupted and turned into a bloodbath. Thus, a modern-day cleansing ritual comes to resemble another, quite different ritual, that of human sacrifice. And with that, redemption goes down the drain like blood—or Bosco chocolate syrup.

If I might add one other way in which the film is subversive, it is with regard to that staple of Hitchcock films, the MacGuffin. The MacGuffin in Psycho is, of course, the $40,000 that Marion steals. That it is money which should play the part of a mere plot device, one that is quickly forgotten once it has served this purpose, is arguably the ultimate subversion in a fully capitalist, modern society. In Psycho, Marion is not killed because she steals the money; she has, in fact, already decided to return it. She is certainly not killed for the money, which is unknowingly tossed into the trunk of her car along with her dead body and the car then submerged in a swamp. The disposal of her body, the reduction of a living being into a lifeless object, is of course, morally and existentially distressing. On the other hand, the disposal of the money, similarly reduced to a useless thing, is, we might say, ideologically distressing.

Nihilism: Not Just the Study of a River in Egypt!

As transgression and subversion tend to be linked, with transgression often leading to or itself constituting a subversion, so does subversion, taken to its logical conclusion, often lead to a sense of nihilism or at least something that feels a lot like it. In Psycho, it is in the film’s treatment of the two elements just discussed, the money and the agency of the individual as a moral being, that its subversion shades into a kind of nihilism. It does so by suggesting that, ultimately, the money, the theft, and the desire to confess and atone (or not) doesn’t matter. Regardless of circumstances or of what you do in those circumstances, your life can still be abruptly and violently snuffed out by a seemingly friendly stranger in the shower of a drab, anonymous motel bathroom during an ostensibly private moment and your body disposed of like so much trash, simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

While Psycho is not quite the fully dystopian, nihilistic affair that Night of the Living Dead is (the kind of horror that would largely define the decade to come), it is nevertheless miles away from the bulk of horror fare that preceded it. Furthermore, while a film that is now 60 years old will inevitably show signs of its age, in Psycho’s case these are merely at the superficial level—the clothes, bits of dialogue, some of the technological limitations inherent to making a film in 1960. In every other respect, the ones that actually matter, Psycho still holds up, something that can’t be said for many horror films that preceded it (and even many that followed it).

Night of the Living Dead, eight years later, has this same enduring quality. While Psycho will always be the original modern horror classic, it was Night of the Living Dead, more than any other single film, that essentially drove the final nail into the coffin of the traditional horror film by upping the ante on the transgression, subversion, and nihilism of Psycho.

Next week: Onward and…downward? Night of the Living Dead largely picks up where Psycho left off and things just get worse as all vestiges of respectability go out the window! See you then!