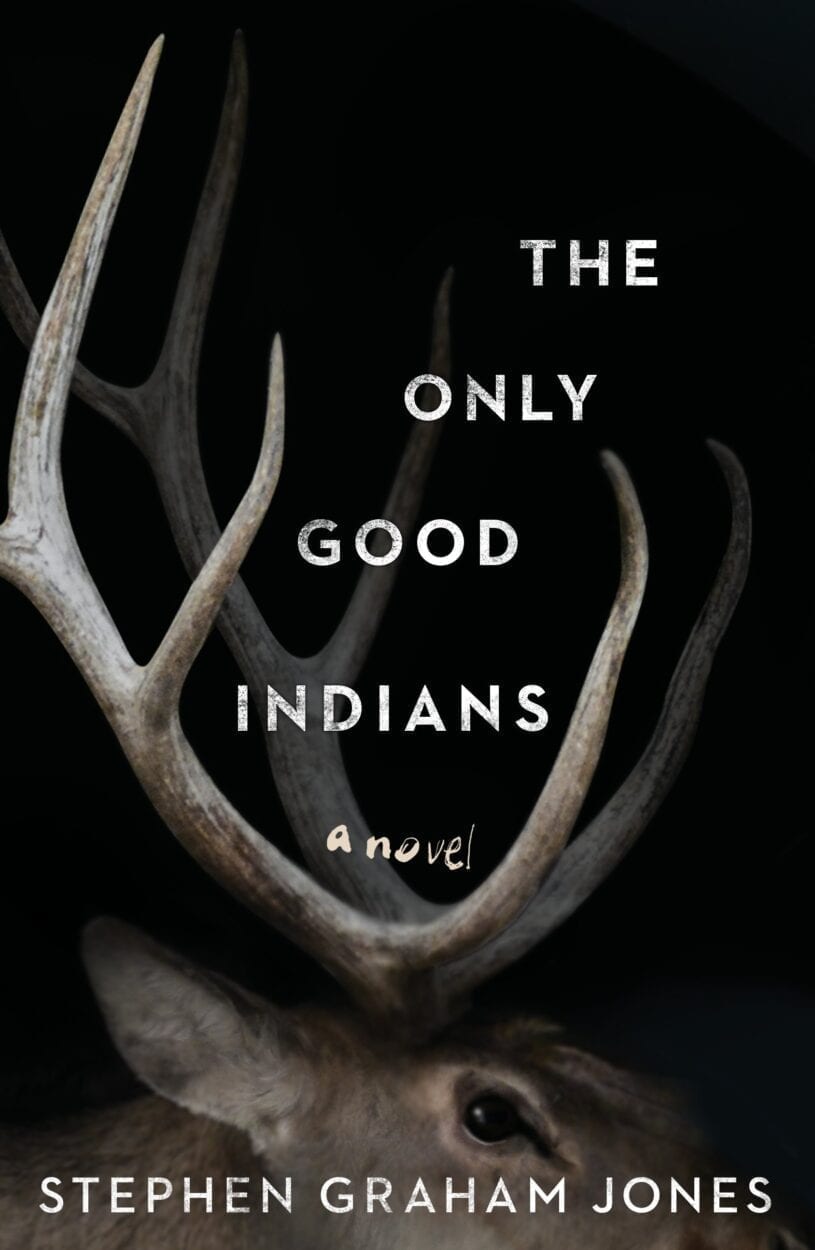

Let’s not beat around the bush: The Only Good Indians by Stephen Graham Jones is the chewiest new read of the summer.

At the novel’s core is a cascade of decisions that four young men made on an elk hunt when they were young. Decisions that were meant to swerve wide of various ethical codes. But the extreme elasticity that Ricky, Lewis, Gabe, and Cassidy exerted on that day snaps back hard, haunting them literally and figuratively years later.

The Only Good Indians belongs to a rare set of novels. It provokes you to read faster and faster because the plotting and horror forms are so brilliantly built that you want to swallow, or be swallowed by, them. Yet, the dynamics of identity and relationships are so sophisticated and subtle that you need to pause, bookmark the page, and tangle with the ideas at play in whatever passage you just read. This tension between plot, formal horror techniques, and theoretical complexity makes The Only Good Indians a masterclass in horror—specifically the chewy kind of horror that deposits a slow-smoldering ember of dread alongside critical questions about living in a mesh of social structures that define and shape people’s lives.

The novel opens explosively with a compact 12-page chapter for Ricky. Other characters’ chapters unfold in their own longer but distinctly-paced burns. Ricky’s chapter opens, and closes, with a pair of phrases: “INDIAN MAN KILLED IN DISPUTE OUTSIDE BAR. That’s one way to say it.” The all-caps statement is what the newspaper headline of the event will read, and the subsequent statement is a narratorial remark. Together, these statements inform the reader that we’re about to enter a tangle of identity and racism, deadly violence, and disparities in how the events are told. At this point in the novel, these combined elements resonate with lived experiences and news stories. But the events of the chapter, in all their humor and terror, reframe the pair of phrases so that on the last page they still include familiar racist violence and journalistic voice as well as the challenges in telling tales of hauntings.

One more note on the first chapter: its title is “Williston, North Dakota.” The setting conjures up fossil fuel extractivism as well as the #NoDAPL Dakota Access Pipeline protests of 2016. What’s brilliant is the way Jones establishes the setting and then leaves that simple act of naming city and state to reverberate through the chapter without making more explicit connections between petro-culture, the ghost elk, Ricky, and the white roughnecks. The horrific history of displacement and exploitation specific to this place inhabits the chapter in an unsettling yet nuanced wavelength. As such, the chapter and novel as a whole are not about the US history of displacement, exploitation, and annihilation, but it’s also not not-about this history of horror, too. Jones’s technique is like a literary equivalent of the David Lynch sound design that’s come to be known as “intense ominous whooshing.”

Having mentioned David Lynch’s aesthetics, Stephen Graham Jones wields a similar acuity in creating unsettling affective juxtapositions. For example, over a few pages in the second chapter, we join Lewis in his experience of wide-ranging emotions as suspicions pivot into a bloodbath. Lewis questions who exactly the other people currently in his life are and how they relate to him through gender and racial identity, and then just as he moves out one meta-level to question how complicit his suspicions are in terms of racist ideologies, the scene goes brutally violent as if driven by a power external to Lewis.

Before readers can recover from this whiplash shift from detective, to intellectual, to perpetrator of violence, Lewis, coated in fresh gore, takes note of his mind absurdly going to the prospect of getting his rental deposit back. It’s a belly laugh moment that intensifies the wide- and wild-ranging montage of embodied affects. Jones has mastered the literary version of this move that Lynch has mastered cinematically, plus, when Jones does it, the discomfort he generates pushes readers to tarry with the critical matters at the core of the people in the scene and the novel as a whole.

A short double detour here to say that if you’d love to read Stephen Graham Jones nerd out on David Lynch’s cinema, there’s a brilliant interview with him by Rob King to check out. And, I couldn’t help but put the instrumental ceiling fan in Lewis’s chapter into conversation with the ceiling fan in Twin Peaks that connects two dimensions within the Palmer house.

Another compelling reason to read The Only Good Indians is the perspective its haunting gives to humans coexisting with nonhuman beings on Earth. For the human beings and elk alike, this is a story of parents and children. Family ethics and instincts run parallel along these storylines. And the elk work like a metonymy for the nonhuman elements of the planet, so that their return to haunt and kill the human hunters who acted unethically may stand in for human ecological crimes of diverse scopes and scales. In this sense, the novel makes an intriguing complement to Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead.

Then there’s also the basketball. Olga Tokarczuk samples William Blake’s poetry in her weird novel of human hunters being vengefully murdered. Jones delivers granular descriptions of practicing and playing basketball with different stakes on the line. It’s zany in the genre context of horror. It’s germane in the historical context of “Indian Schools” in the US where basketball was supposed to serve as a tool of assimilation but was torqued instead to function as a resistance tool of détournement.

What’s more, basketball is what makes the novel a work of love and quirk rather than a smooth running attempt to match a writer’s workshop algorithm for literary genre fiction. In a wonderful, goofy way, the basketball in The Only Good Indians pinged for me the memory of those Scooby-Doo episodes when Scooby, Shaggy, Velma, Fred, and Daphne crossed paths with the Harlem Globetrotters. Investigating mysteries and shooting hoops may seem a counterintuitive partnership, but it works since they both involve anticipating the other’s moves, concentrating offensively and defensively, and drawing on fundamental skills and spontaneous intuition.

Finally, the Final Girl. Summaries of the novel focus on the four men in the hunting party. But women feature prominently across the three long chapters, and if we count the cow elk, across all the chapters. Among the women in the novel, the most thrilling and forceful is Denorah. She’s a prodigy on the court, though on the court Denorah must constantly negotiate who she is by what moves she executes and resists. She brings her tenacity and competitive drive to the final showdown of the story as well. When she was younger, Denorah acquired the nickname Final Girl from her father, but it’s in reference to a basketball tournament, giving the well-known horror genre trope a twist.

Denorah’s nickname innovation is clever in itself, but it also directs readers’ attention to the values, struggles, and ideas that come bundled up with her specifically as the novel’s Final Girl. You get the distinct impression that Jones has put the Final Girl moniker to work with a philosophical sense of the critical potential the trope holds, as Carol Clover and others following her lead in Men, Women, and Chainsaws have explored. At heart, the novel innovates brilliantly upon the conventional horror trope of the Final Girl, and bundled with this new embodiment is an intersectional perspective on American history as American horror.

That’s what sets The Only Good Indians apart from so many other horror novels, and really just other novels in general: a wellspring of complex critical ideas percolating within the dextrous storytelling and oddball sense of humor.

Imagine the smartest, weirdest parts of Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You, Lucile Hadžihalilović’s Evolution, David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, and Nick Estes’s Our History is the Future. If that sounds amazing, then crack open The Only Good Indians.