I’ve been in a committed relationship for well over six years now. I am not who I was when the relationship began. That person is dead, and I have been twisted into shapes that share features with the deceased but only in passing. That person died the day the relationship began. My partner died that day as well, our identities and personalities mixing and twisting, shaping us anew. The people we were can never return. In that truth, there is pain and anxiety, happiness, and love. At its core, the transformation is terrifying.

We can reckon with the inhuman monster or unrelenting killer. They exist outside our scope of normal life. A terrifying presence, to be sure, but one that we will most likely never encounter. We can stop the movie or put down the book and the fear will dissipate. There isn’t a monster in your closet. Don’t believe me? Check.

But how do you know that your guts aren’t moving on their own right now? Can you feel them slither? Are you sure? How do you know your best friend is who they say they are? Maybe they are human. But maybe they’re just biding their time.

Or maybe your body is betraying you in a more grounded sense. Maybe you have an incurable disease that eats away at you from the inside. Maybe your friend isn’t anything more than human. But maybe they’re spreading lies, betraying the trust you have built with them.

Body horror touches on the anxieties that are central to our identity. Conventional horror wants you to feel fear and fret for life, but body horror wants you to feel betrayed, wounded by the things you trust. When your innards start leaking out of their own accord, when your friend removes their head to reveal a squirming mass of flesh, it’s the betrayal that sticks. The awareness that the trust in your loved ones or yourself was misplaced. It creates a mixture of revulsion and pain, watching ourselves and those we love warp into things we do not and can not understand.

Nobody trusts anybody now, and we’re all very tired.

Trust is a hard thing to come by. It’s an invisible connection that ties us together based on very visible actions. You may trust your neighbor, who once returned mail that was delivered to the wrong address. You may trust your spouse, who you’ve spent decades with. You may trust your dog, who curls up to your feet every night. But you’ll never truly know what’s happening in that person’s mind. Or under their skin.

1982’s The Thing is among the first films people connect to body horror and for good reason. The first real glimpse we get of the Thing is as a dog, slowly splitting its own body open, lashing out with arteries and tendons at other dogs. It’s a horrifying scene, immediately putting distrust front and center as “man’s best friend” betrays the confidence humanity has put in canines for thousands of years.

Taking place almost entirely within a single arctic base, the Thing slowly picks off the crew, replacing them with doppelgangers created from itself. Fire seems to be its only weakness. The crew quickly descends into paranoia, the building blocks of trust left out in the snow with the scorched bodies of their comrades.

The Thing is structured so that even the viewer is never fully clear on who has been replaced and who remains human. As a result, everything in the movie feels tainted by doubt and mistrust. Maybe even our hero is one of the Things. The basic principle of trust in film breaks away, leaving everyone paranoid and afraid, including the viewer, that anyone on screen could be hiding something horrifying just beneath the skin.

The terror of The Thing is not the body horror, though it serves to accentuate it. Rather, the true terror lies within us all. We can never truly know what others are thinking, where their trust and alliances lie. The Thing brings this truth to light in visceral, bloody ways that attach our own insecurities to a creature that represents the betrayal within us all. What we fear in The Thing is not the Thing, but a lack of trust.

…[T]he person that started this journey won’t be the person that ends it.

Here’s a simple question: Were you thinking about body horror before you started reading this piece? Had you examined it as a reflection of the death of the self before? Are you sure? Can you trust yourself?

Now, to be clear, I’m not here to say I came up with this concept. Far from it. But I’m not really sure where I got the idea. Maybe it’s new, maybe it’s been kicking around in my brain since I saw Annihilation two years ago. Or maybe I passed someone in the street muttering to themselves and I picked up just a few words and created this.

That’s the central conceit of Annihilation. We are refractions of one another. Your experiences will shape mine. And at that moment, I am destroyed. Am I still Sean, or have I been replaced with someone new? Was your decision to read this piece your own, or the will of someone else, subtly influencing your lived experience?

The Shimmer provides one of the greatest explorations of self-destruction and rebirth in film, without fully engaging in either. The Shimmer is a strange field, created by a foreign object crashing to Earth. Everything within it becomes unified, reflecting everything around it. Plants form human shapes, flowers merge into a singular species. Tattoos shift from person to person.

Annihilation‘s body horror isn’t as obvious as The Thing‘s or Panorama‘s. Its subtle, little changes are reflective of experience. They’re changes that outsiders wouldn’t notice, but the characters do. It’s a slow, creeping horror that the people that entered the Shimmer aren’t the people they are now.

When the crew of scientists sent in to explore The Shimmer stumble upon a memory card from the last expedition, each of them is touched by the experience. The card contains footage of a man being cut open by his allies to reveal his own intestines moving, writhing like snakes within his chest. The new crew reacts harshly, some denying, some shifting into panic mode. One crew member suddenly has a tattoo on her arm. The same tattoo that was on the man who was sliced open.

That same tattoo appears on Lena (Natalie Portman) during her interview scenes. Whether anyone in the team realizes it, they have been inextricably changed by this interaction.

At the finale of the film, Lena reunites with her husband, Kane (Oscar Isaac). The reunion is fraught. They both know what they saw in the Shimmer. They know neither of them is the same person they once knew.

Time changes all of us. When you leave your house, you will not return as the same person. Maybe on your walk, you saw a tweet that recontextualizes your sense of humor. Maybe you had a sudden thought that triggers a change in career. Maybe you saw an act of violence that shook your faith in humanity. Every day we are twisted into something new, something unrecognizable to the you of the day before.

To paraphrase Annihilation, our skin is always shifting. Our flesh is liquid.

We’ll be a real couple. We’ll be inseparable.

You know the couples that lose their identities? They’re no longer “Taylor” and “Alex,” they’re “Taylor and Alex.” One is rarely seen without the other. And when you do manage to isolate one, they spend the whole night talking about their other half or just texting them. The “I” is gone. “We” is all that remains.

Identity is the core of body horror. Knowing your identity, your friend’s identity, the world’s identity. To witness someone’s identity stripped away is to see them replaced by nothing more than writhing flesh. And so it is with relationships. Two becomes one. Your identity is lost in a melding of flesh, even if you aren’t the “we” type of couple.

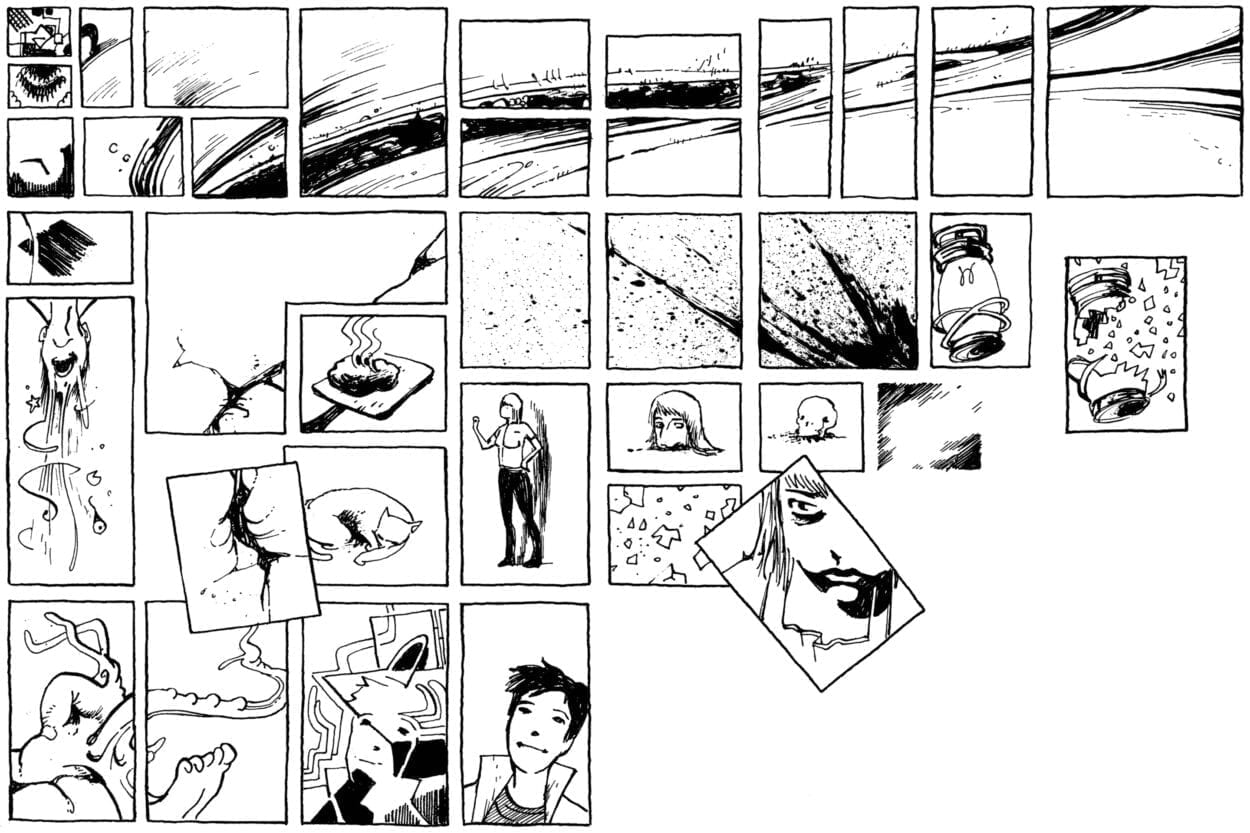

Michel Fiffe’s graphic novel Panorama utilizes body horror to explore the anxieties and identities in interpersonal and romantic relationships. Augustus is first seen struggling with his own being, unsure who he is as his skin acts on its own impulses. As he begins to realize that his flesh is his to control, his girlfriend, Kim, comes to the city. A night of adult fun-time later, and Augustus is absorbed into Kim through her lady bits.

Panorama doesn’t really frame Kim as the villain. Instead, it turns her into a second protagonist. Augustus lives on inside her for a while, before eventually fading into her completely, but this isn’t presented as an act of animosity. Instead, it feels like something natural for a young adult in a new relationship. The experience is fresh and she’s unwilling to let it end. Augustus has become a part of her and, despite the fact that it is literally killing him, she’s unwilling to let him go. He was her first love, after all.

As shown in Annihilation, every relationship permanently changes a person. But romantic relationships go beyond, even ones that don’t become toxic and harmful like Augustus and Kim’s. Romantic relationships meld your being to your partner’s. They shape everyone involved into new people while fusing lives together. Break-ups and divorces are hard for a reason. Every facet of your life has become entwined. Friends and property are shared. Children and pets are loved equally. Everything in your life becomes part of a whole and removing yourself from that whole requires a severance equivalent to surgery sans anesthesia.

It wasn’t destroying. It was changing everything. It was making something new.

To equate interpersonal relationships and, indeed, the human experience to body horror sets a negative connotation around the whole thing. Why trust when they can betray, why interact when it destroys the self, why date when you lose your identity? But I don’t think that negative connotation is deserved. Have you ever seen inside someone? Our bodies are gross. We are horrible. But that’s also what makes us beautiful.

Every time we trust, we grow as people. It’s part of who we are. Sometimes the people we trust can use their arteries as whips, sure, but all you need to do is burn them alive and you’re good to go. For every movie that sees people emotionally torn apart by monsters, there’s one that brings people together.

Every new experience builds our strength. Some will scar us. But they will also bind us to others who will fight with us and support us. Maybe today’s experience was a bear that screamed like a human. But hey, someone else has probably dealt with that and knows how to help. Maybe it’s you. Every day is a chance to leave a positive mark on someone.

Every relationship has the chance to build our support network. Sometimes they’ll eat you whole (and you shouldn’t thank them for that—fuck abusers), but sometimes people will come together to make something bigger than themselves.

Everything is disgusting. But everything is beautiful.