There are a lot of fun tidbits about Steven Spielberg’s 1975 obscure little film called Jaws. It was the first summer blockbuster, or that it maybe aids in helping to solve a decades-old cold case come to mind. The coolest part about Jaws to me, though, is how the film can be read as an allegory of the American response to underrepresented groups. Steven Spielberg, a Jewish man himself has commented about how much his roots have impacted his life, and by proxy, his films, as well. One could see then that Spielberg could integrate the oppression of his ancestry as a cautionary tale against ethnocentrism and the treatment of underrepresented groups.

As Jaws opens, with a beautiful score by the legendary John Williams, we see a group of teenagers enjoying a fire on the beach with plenty of alcohol and hormones. Teenagers, often depicted as the epicenter of rebellion, promiscuity, and idea corruption signal a perfect storm for this allegory to take off. Let us remember back to the 1936 film Reefer Madness for a perfect example of the “we must save the teenagers” trope. In the film, a group of teens was corrupted into becoming addicted to “reefer” cigarettes—their innocence forever stripped away as they gave in to the evil that surrounded them. Since Reefer Madness, it seems, the swaying of teenagers has been used to determine whether the new group of perceived threat is succeeding or not. This first shark attack claiming the life of a teenager, then, follows a well-trodden path of encroachment allegory.

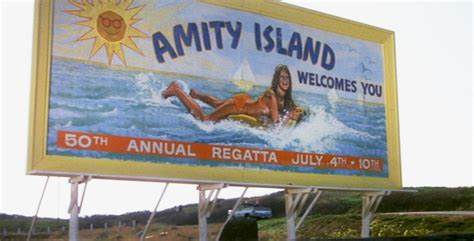

Immediately after this attack, we meet the first of the characters playing a role in the allegorical context—the ally. Chief Brody (Roy Schneider) an “outsider” afraid of the water has moved from New York to the community-centered Amity Island, where everyone is friendly to one another. “Amity means friendship” after all, and all of the residents have an “it can’t happen here” vibe. It is when we meet Chief of Police Brody that the distinction between “islander” and “outsider” becomes prevalent. Brody is not as quickly trusted by the rest of the town because he was born somewhere else, and that somewhere else was away from the water. He is believed to navigate the world differently because he is so radically not used to the way of life of Amity. Nevertheless, it is he, an outsider, who comes into this community and when faced with tragedy, jumps with the most gumption to ensure the health and safety of the community compared to those who have spent their whole lives on the island.

It is not for nothing that Chief Brody is afraid of water yet moves to a beach town where most of his day seems to be spent close to the surf. “It’s only an island if you look at it from the water” he says when asked why he would put himself in this situation soon after being told “You’re not born here, you’re an outsider, that’s it.” Brody is clearly perplexed by this distinction, he obviously never expected to have to prove himself worthy of being able to protect a town from itself. His first instinct upon finding out that the teenager fell victim to a shark attack was, naturally, to close the beaches. But he really finds out what he’s up against when the audience is introduced to everyone’s favorite inept Mayor Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) who vehemently opposes Brody’s plan to shut down the beaches.

In a move that’s all too similar to the way in which beach states have handled their re-openings in the midst of COVID-19, Mayor Vaughn is all too eager to keep the beaches open, stifle word of the shark, and keep the town’s way of life and income stream going. Money over safety has become something we have all grown accustomed to living through a pandemic, and Mayor Vaughn seems to be held up as an example to emulate by many world leaders on how to respond to a threat to citizens. In a response to Brody’s persistence toward his plans of closing the beaches, the townspeople go after the threat to their livelihood that looks historically like the response efforts of many factory towns reacting to an influx of labor and working classes. The immediate reaction is to name the threat, then push it out which will certainly seem familiar to the ostracizing attitudes towards many first-generation immigrants, especially in a town as insulated as Amity. “They’re not my people, did you see the license plates? Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Jersey, they’re from all over, I’m all by myself out there” is one deputy’s response to the arrival of non-locals looking for an opportunity to act violently and aggressively against that which they do not understand.

Much mention is also made of the size of sharks’ mouths and how they will eat and swallow anything without regard, even trash in the ocean. In the allegorical sense, this could be Spielberg’s echoing the fears repeated by homogeneous groups that suddenly find themselves overwhelmed by people that look different than them. It seems as though every time a new group immigrates to an American town, the cry from the rooftops is that the culture and way of life of the dominant group will be swallowed up and regurgitated in an unrecognizable form by those who have newly entered the community. Another all-too-common claim is that those that move to this country only want to steal jobs and have babies. A poignant bit of dialogue supporting the Jaws as an allegory claim is when the shark is referred to as a machine and one that only “swims, eats and makes little sharks.” And this killer shark, or immigrant, that takes the life away from the locals and further implants little versions of itself as culture thieves creates an enormous threat to the Amitys of the world described as a “cloud descended upon the island.”

Then, of course, there is the rather obvious fact that this shark attack occurred just before Amity’s biggest tourist weekend and moneymaker—the July Fourth American Independence Day celebration. The American way of life, which many will have you thinking is always in danger, certainly must be preserved and protected on the holiest of days, Independence Day. Mayor Vaughn seems willing to accept whatever takes place just to show his patriotism by having the beaches open during the holiday. Word can be diminished enough to keep people visiting and flocking to the water, he believes, and whatever needs to be done about the “shark problem” can be properly attended to after the festivities.

In the end, it is two outsiders who come to the best defense of the people of the island, as so often happens in real life. Many times, it is those who are too deep in the forest to recognize the trees. Water floods the boat, seeming to indicate the inevitability of incoming people and cultures. Brody overcomes his fear of the water because he is needed to keep the town at large safe. The old way of life dies trying to overcome the arrival of what is new and different to the small town. Only those who treat the shark with reverence and awe can overcome the danger it presents. What was vast and scary in the water, can come to be expected and respected. A town that makes its living encroaching on land that is not theirs must contend with that reality eventually, as Amity had to. Like people, water is everywhere, and only once we make peace with the positive changes it can bring can we see the beauty in a rainy day, even if it rains on the Fourth of July.