As someone who talks about and writes about films, particularly horror films, I like to talk about genre. Genre gives us a lens through which to view movies. It becomes a kaleidoscope of history, a new image set against the numerous things that came before.

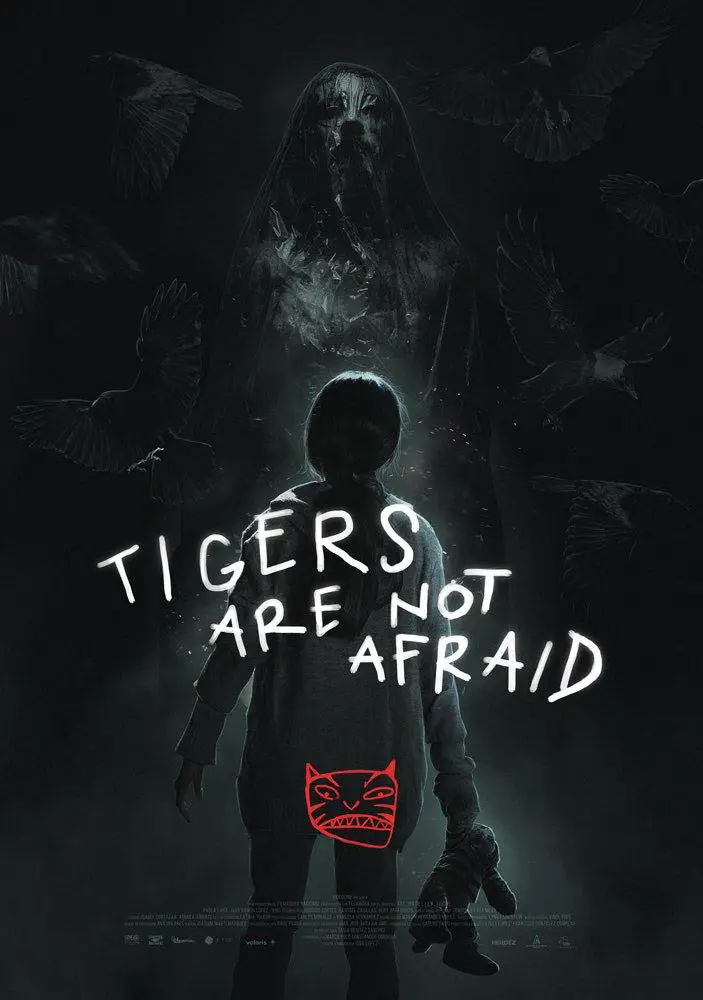

Every so often, though, genre fails me. A film comes around with no obvious tradition, no parentage and seems, at first, to be an orphan of cinema, bold, fearless, and unique. Such an orphan is Issa López’s Tigers Are Not Afraid.

Written and directed by López, Tigers is the story of children living on the streets of Mexico underneath the looming shadow of a brutal drug war. Even against this bleak backdrop, however, López finds proof of magic. This should come as no surprise, however, for as long as children exist, so, too does magic. Tigers is a tear-streaked letter to the modern world, begging it not to forget either.

It does not escape me that, as I praise a movie about tigers, children, and their struggle to escape the various confining, bleak circumstances, I live in a country that cages children. Mexican children. In a time where the powers that be scream and spit and tweet to distract, Tigers asks that we observe and cherish the humanity, the complexity, and the reality of children.

The film works tirelessly to instill a magical realism to the stories of the children, Estrella, Shine, Tucsi, Pop, and Morro. We are told, right from the beginning, that this is a fairy tale. It is a story of princes who forgot they were princes, who must become tigers to survive. López’s stunning visual style for the film, the way in which so little can mean so much, gives us and the children an arsenal of metaphors to fight our way through these times. The sound design, particularly surrounding the film’s many ghosts, is unrelenting, deafening. The dead and forgotten of Mexico will not be silent; they will have their say. They are also—to this reviewer—real. They are visceral and physical and vindictive. They won’t be dismissed.

The children themselves, particularly Estrella and Shine leap from the screen every second they’re on camera. Paola Lara, the young actress, delivers an unrelenting performance as she crawls through every emotion in her fight to survive. She is playful, fearful, clever, and brave. She is, in the only applicable and highest accolade an actor can achieve, human. So, too, is Juan Ramón López as Shine, the leader of the orphan gang Estrella joins early in the film. His struggle against the various hurts and scars he bears while remaining tough and trustworthy to his gang has all the indicators of an actor with forty years of experience.

Tigers also has the patience to tell its whole story, rather than tell a shallow melodramatic story that fetishizes the violence and trauma of crime-rent Mexico. There are moments that reach out and touch the viewer and force them to feel, to take in the entire reality of these kids and the world they live in. When Shine first tells the story of the Tiger, a bedtime story surrounding a rich man’s house and his escaped pet tiger that now roams the slums of Mexico looking for its next meal, the boys sit in rapture, afraid, as though, for a brief dark moment, there is nothing to fear but the story being told. When Estrella leads the gang to an abandoned mansion and they stumble upon a puddle full of exotic fish, refugees from a nearby fish tank, there is a raw emotional escape in the way they watch them swim, happy in their new home just as they will hopefully be. I’m not embarrassed to say the fish made me cry.

Color, too, plays a large part in López’s film, bursting through the film only in flashes: the bright blue of Estrella’s mother’s house, the orange of Morro’s stuffed tiger and fire. Most of the film lives in a bleak desaturated world, the only vibrancy brought by the children themselves.

That Estrella means star, and that she is granted three wishes at the film’s beginning also intentionally leans on the iconography of fairy tales. These dreams and magicks have their place here too, and give hope to those who refuse to be hopeless. López herself, in this film, seems full of hope and courage, believing both are necessities rather than luxuries. So too here though is blood and death, manifested in the film as a thin red line running throughout the story. There’s a line as long as history connecting us to this violence. We too have a role and a place and a means to end its creeping trajectory.

Beautifully paced across eighty-six lean minutes, Tigers focuses on what matters to López, what should matter to us. The children fight, they friendship, they plot, and they play. Like the ghosts, like the tigers, like the caged children this country would like us to ignore, that this country wishes we would just forget about in the midst of a country gone crazy, they are real.

Tigers plays by no rules of genre because it wants us to focus on its story, on its children, on its eighty-six-minute fairy tale about children in peril that must be brave, must be human, must dream and tell stories. Because of this, Tigers is a horror film, a children’s movie, a coming-of-age tale, a love story, a drama, a comedy, and the best version of them all, all at once. López takes talented, fearless command of each genre to say in no uncertain terms that Mexican stories are all of our stories and we need to act accordingly.

She is telling this story to beat back the silence and indifference that would swallow stories like hers. To watch Tigers Are Not Afraid is to understand that you have a responsibility to these fairy tales and wishes and children. We must see their humanity. We must champion their stories. We must make them come true. It will not be easy. It will be scary at times. But we are not powerless in the face of this apathy. We are princes. We are tigers. And Tigers are not afraid.

For more information on how to help, visit The Immigration Defense Project or the Immigration Advocates Network