I remember moments with my best friends in high school spent in basements of each others’ houses. One of the only ways to pass the time that didn’t involve burning army men or underage drinking was watching movies. The rules were simple enough: your house, your movie.

Most of the time this meant watching Happy Gilmore or Billy Madison or another comedy built on the back of yelling and slapstick (nothing against that, by the way, I still defend Adam Sandler and think Sandy Wexler is better than you’d believe).

When it was my house, though? When it was my movie? Friends would roll their eyes as I blew the dust off my too-big binder of DVDs and pulled out a horror movie. The best horror movies, the ones I loved, burned slow and hurt every minute of the way. Getting anyone in high school to sit through Videodrome (1983), Suspiria (1977), or Rosemary’s Baby (1968) long enough to get to the payoff is a challenge, but the endurance is worth it.

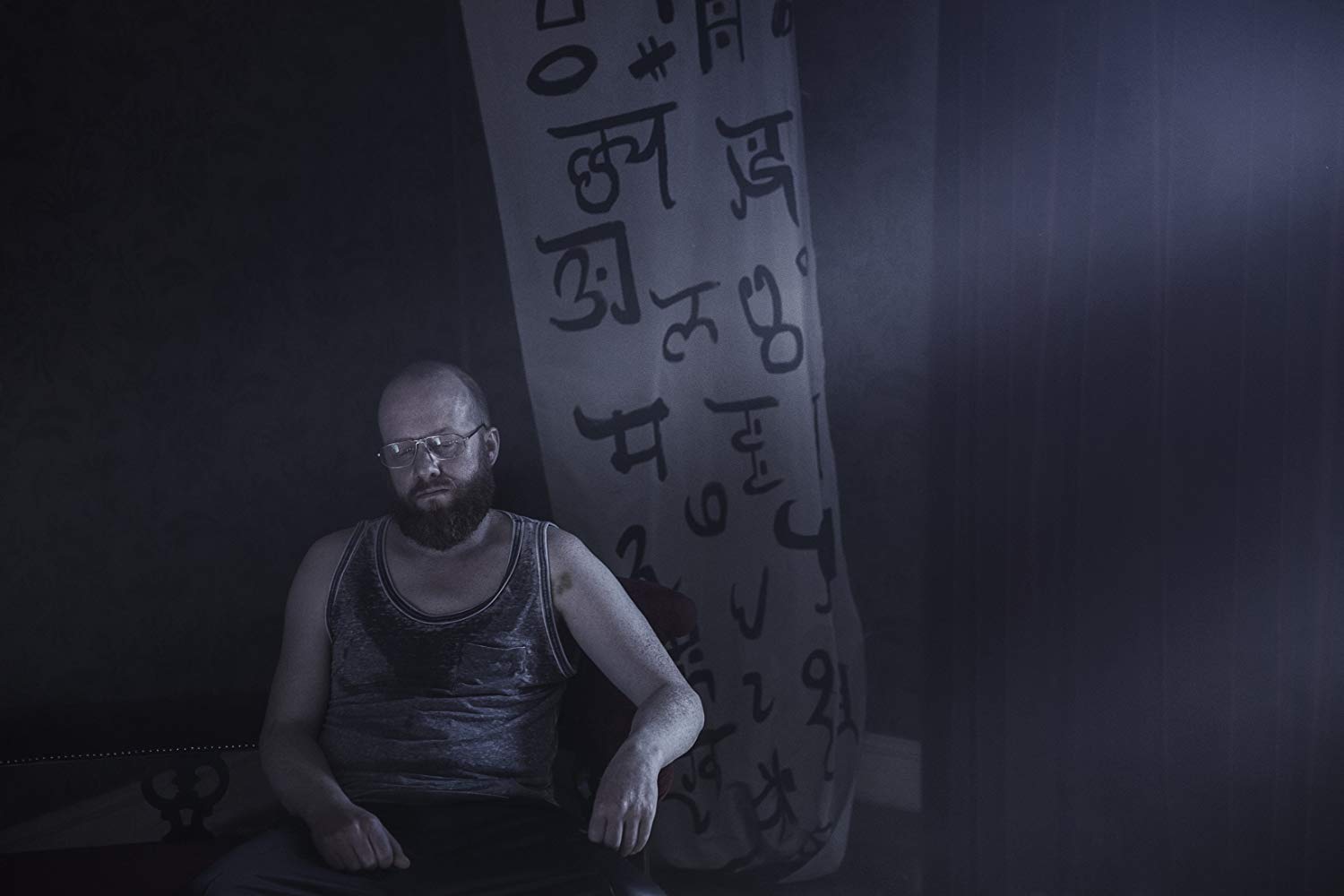

Liam Gavin’s 2016 indie horror A Dark Song makes me feel like I’m back in those basements, enduring all that uncertainty and tension in the hopes of something greater. The film spends its lengthy running time mostly with a desperate young woman, Sophia (played by Catherine Walker), and a jaded occultist, Joseph (played by Steve Oram) as they perform a months-long ritual to contact Sophia’s guardian angel and have it grant them each an impossible wish.

Two Humans and a House

The film kicks off with one of the most inventive, exhausting, and cathartic premises for an indie horror experience that I’ve seen in years. The ritual requires that the characters have no contact with the outside world, realistically creating a two-person story with one location. Joseph demands Sophia endure various cruelties: sitting in one room for a week with no food and only some water, being doused with cold water, drinking blood. These grueling acts are to purify her, to make her worthy of an audience with her guardian angel. She must survive and endure them to prepare herself.

The austerity of the film’s front half keeps everything shrouded in ambiguity. Joseph’s magic is esoteric, inaccessible, and seemingly convoluted, but Sophia believes it is worth it. When sealing the ritual site (an old manor house Sophia purchased with her life’s savings), Joseph encircles it with a large ring of salt. Right before he completes he asks her, one last time if she is willing. She agrees, the circle is complete, and the ritual begins.

Keep watching

Every movie, to me, is about the movies in some way. A Dark Song could easily be a dense gothic novel or a stage play, but it is not. A Dark Song is a horror movie and it offers us a greater perspective on why we, as fans of this sometimes cruel genre, endure what we do. After all, what are horror films if not the songs we sing together in the blue glow of the flickering face of our God?

Throughout the story, Joseph interrogates Sophia about her motives for this ritual, and her answers continue to change. So, too, do our answers for why we watch a movie like A Dark Song. What are we after? Is it to test ourselves, and our ability to endure depictions of pain, of fear, and vulnerability? Is it some spiteful craving to see the many, small, repressed violences of the day played out on screen like some therapeutic roleplay? Are vicarious masochists? Sadists? Both? What was I trying to find in those basements with my reluctant friends in tow?

Catherine Walker and Steve Oram give naturalistic, grounded performances that breed empathy. Sophia’s sacrifice and Joseph’s reluctant witness feel as real as anyone you’d meet on the street. Liam Gavin’s direction of the camera also persists without making its presence known with stylistic flourishes or dynamic angles.

This choice ensures that the film doesn’t feel like an authored experience, but an observed one. It makes their forays into the supernatural easier to swallow. The film’s slow beginnings plant seeds of doubt the same shape and potency as Sophia’s. She wonders if Joseph’s elaborate ritual and dark magic will be real. We wonder if Liam Gavin’s will be.

A Higher Purpose

I’ve watched people in horror films be stabbed with knives, beaten with tree branches, eaten by dogs, impaled on a mounted deer trophy, and more. I’ve endured so many convincing screams and pleas for mercy and watched on with indifference, all the while searching for something. A Dark Song approaches human suffering with a similar, seeking agenda.

Perhaps that is its greatest strength. It reminds me, with each minute of our time together, that suffering has a purpose—that it means something. With every soulless cash-grab slasher film, I feel my grasp of that purpose fade away.

With an even more distant view, I find myself wondering about the purpose and worth of violence watching the news. A Dark Song answers that wonder with no uncertain terms, the violence and suffering must have a purpose to be worth anything. To be worth singing.

When Sophia answers Joseph’s question for the last time, I felt a kinship with her on a deeper level than a vicarious victim or a talented actor. I felt like she and I were in this together. That we were singing this dark song in harmony, each for different reasons, both for the right ones.

A Dark Song is a slow, strong serious story with great actors and clever, sparingly employed special effects. Streaming on Netflix now.

Perfect Double Feature With: The inventive and terrifying Turkish, taut occult police thriller Baskin (2015).