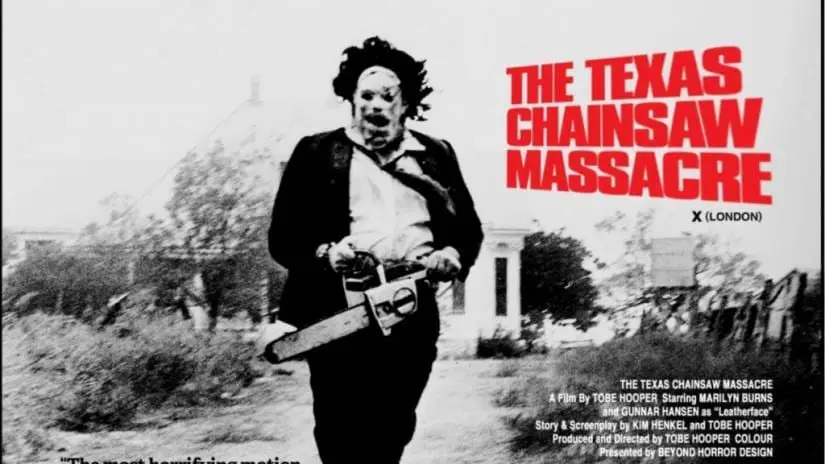

Tobe Hooper died in 2017 but his indelible mark on the horror genre and cinema at large will outlive us all. If Hooper had solely made Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), he would be welcomed into horror heaven with open arms. The original has often been duplicated but never bested in the 44 years since its release. On a shoestring budget of less than $140,000 dollars, Texas Chainsaw Massacre reinvented horror overnight. It’s impossible to accurately tell the story of the evolution of the genre without an examination of this film. The influence of TCM was felt far and wide. Other genre luminaries like Wes Craven (The Hills Have Eyes), Alexandre Aja (High Tension) and Rob Zombie (The Devil’s Rejects) all owe Hooper a great debt. The auteur didn’t stop with TCM and went on in the subsequent decades to make several genre-defining classics, both praised and overlooked, making him a true icon horror icon.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

Tobe Hooper hailed from Austin, Texas and spent his earlier years teaching college and making experimental hippie films like Eggshells (1969). Tobe and co-writer/partner Ken Henkel wanted to explore hixploitation films like Herschell Gordon Lewis’s 2000 Maniacs (1964) in a much more serious fashion with a counter-culture political message at its center. The shoot for TCM was absolutely grueling and deserves a book all its own. There was absolutely no extra or outside funding, so everyone suffered. Hooper and company spent seven days a week on the film, sometimes working over 16 hours in a single day. A lot of the cast were really not happy with the bleak material and distanced themselves from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which has often been a focal point for groups advocating for censorship due to the graphic, realistic depictions of violence in the film.

If only they all knew what they actually had on their hands at the time. Texas Chainsaw Massacre is more than just a horror film or a slasher progenitor. There has truly never been another film like Hooper’s original. Like The Honeymoon Killers (1960), TCM was shot in a way that made the viewer feel like a fly on the wall of the most disgusting room possible. The film was based partially on elements of real-life serial killers Ed Gein and Elmer Wayne Henley, and the opening crawl narration sounded like Walter Cronkite reading a news brief of the horrific events surrounding Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) her brother Franklin (Paul A. Partain) and their friends’ disappearance. Audiences were absolutely terrified as no one was quite sure just how real what they were seeing actually was. Hooper shot the film in a style that could be described as cinema verite but looks much closer to a home video found in the basement of a serial killer.

The America of Hooper’s TCM was a direct and honest look at the South that only someone from that part of the country could honestly portray. Before any of the characters are introduced, news briefs reminiscent of the TV broadcasts updating the zombie apocalypse in George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) play over a surreal score that’s more ambient noise that creates an uneasy feeling than music. It’s hard not to imagine David Lynch seeing the film while making Eraserhead (1977) and wanting to emulate that feeling. That’s just a thought though; there’s nothing I can find suggesting that was in any way the case. The bigger point is that Tobe Hooper was tapping into the collective unconscious of the dark underbelly of Americana in 1974. Veterans were returning to an often hostile unwelcoming home from the Vietnam War just two years prior. Many were homeless on the streets and already in prison from failure to adjust back to life in a so-called regular society that was ill-equipped to deal with mental health issues like PTSD.

No one could be trusted in 1974 either. The Watergate Scandal had finally caused President Richard Nixon to be the first and only President in U.S. history to resign in criminal disgrace. The hippie counterculture “summer of love” in 1967 had spiraled into a death rattle of psychotic drugged out homeless ex-teens. The promise of free love had led to the Manson Family Tate and LaBianca murders, two of the most grisly crimes in American history. The Rolling Stones Altamont concert, foolishly hiring Hell’s Angels members to work as security, ended up in cold-blooded murder. The economy was headed toward a recession and the idolized Mad Men-like Eisenhower America was never coming back. Hell, it was never even there to begin with.

All of this souring of the idea of American Exceptionalism plays into Tobe Hooper’s original TCM. Henkel and Hooper’s story focuses on the cannibalistic Sawyer family in rural Texas; out of work slaughterhouse workers who were abandoned by the companies, state, and country that they put all of their hard work and faith into. Hooper takes that idea to its most extreme conclusion, with Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) and the rest of the white trash Sawyer clan hunting down and capturing travelers and committing unspeakable acts of torture and murder upon them. There’s nothing left in Texas, and even in 2019 driving through the country, it’s easy to see that millions of people have simply been left behind to fend for themselves.

Tobe Hooper’s film felt absolutely real and an attack on the entire American system while also painting a grim subversion on the idea of the “pastoral life.” White people were fleeing the cities in droves in the ’70s to move to the idyllic-seeming country, and TCM serves as a warning for people to stay out of places or they might not like what they find. When the entire country leaves people to rot in the middle of nowhere with no resources or education, the dehumanizing process starts a lot faster than you might tell yourself. Tobe Hooper wanted people to see his grim vision of America and then see how many yuppies and suburbanites still wanted to stick around for dinner.

Salem’s Lot (1979) and The Funhouse (1981)

After teaming back up with Ken Henkel for his TCM follow-up Eaten Alive (1976), Tobe Hooper was offered the job of directing the made-for-television film adaptation of Stephen King’s vampire epic Salem’s Lot (1979). Constricted from using the same type of gore that he had relied on in his previous efforts, Tobe Hooper went in an entirely different direction on his latest film. Hooper drenched the picture in a gothic atmosphere that was very reminiscent of earlier British Hammer Horror films. The vampire design itself was a throwback to W.F. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1929). Salem’s Lot proved that Tobe Hooper was more than just a one trick pony and opened up the door for him to take on different types of projects for the rest of his career.

One of my personal favorite Tobe Hooper films is one of his most initially overlooked: The Funhouse (1981). The premise is simple yet disturbing enough to qualify as one of the most unique slashers of the era. Hooper also uses a very playful use of color that wasn’t typical of many slashers of the day. A group of teenagers go out to a carnival for a night of fun but are soon terrorized after being locked in at closing time. Hard rocker and writer-director Rob Zombie is often noted as having a fixation with Texas Chainsaw Massacre but The Funhouse bears just as much responsibility for the shock rocker’s output as anything else. Love or hate Zombie, he’s one of the biggest names in horror today and a fascinating individual who really knows his cinema. Rob Zombie’s debut full-length, House of 1000 Corpses (2003), is pretty much The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Funhouse thrown into a blender. Why anyone would have a problem with that at the most basic of levels is beyond me.

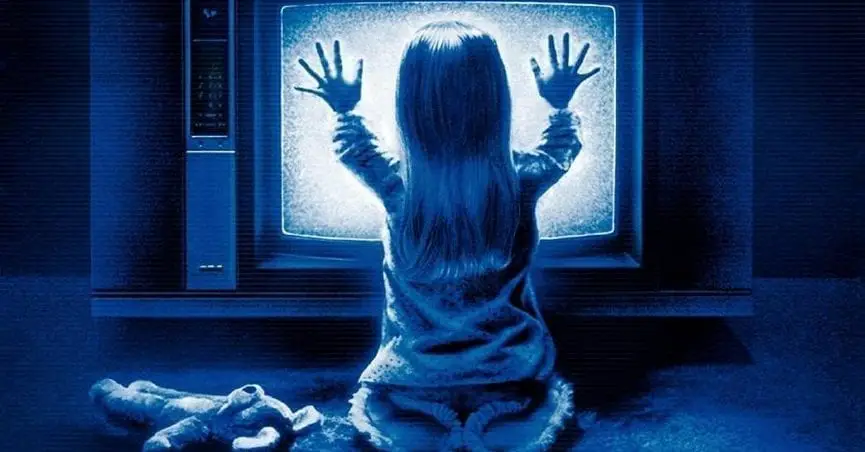

Poltergeist (1982)

The biggest mainstream film by far, and the most contentious, of Tobe Hooper’s career is the three-time Academy Award nominated film Poltergeist (1982). Co-written and produced by the hot young director of the day Steven Spielberg (Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark) the collaboration is one of the most unlikely in cinematic history. The ‘behind the scenes’ tale of the film is also one of the most fascinating that could fill books but basically boils down to an argument that Steven Spielberg was the actual man directing Poltergeist. So what was Tobe Hooper allegedly doing? Acting as more of a first assistant director according to some who worked on the film. It was a sort of scandal even as the film was being made.

Spielberg allegedly had a contract stating he could not direct any films until E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) was delivered in full so he directed the film in secret with a sort of gentleman’s agreement that Tobe Hooper would receive the director credit with Spielberg actually calling all the creative shots along with producing and co-writing. This isn’t really fair to the legacy of Tobe Hooper. Just as many examples one can find of someone claiming to know for a fact that it was really Spielberg, you’ll dig a little more and find just as many that were there claiming Tobe Hooper was the director of Poltergeist. Either way, it’s a discussion for a different time.

What is known is that Tobe Hooper thankfully took Poltergeist out of science fiction and into the realm of horror. Spielberg had wanted to make some sort of quasi-sequel to Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Whatever that would have looked like certainly wasn’t the film we got. Poltergeist feels more in line with the spirit of Tobe Hooper’s political statements on America than anything Steven Spielberg has ever had to say. The entire crux of Poltergeist is that white suburban yuppies, the same failed generation chastised by Tobe Hooper and Ken Henkel in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, were doing just fine dancing on the graves of Native Americans. Past all the brilliant haunted house thrills and classic spook show chills, Poltergeist is a film about American greed and racism. The foundations of the country were built on rotten ground from the start, so all forevermore who dwell here are haunted.

Poltergeist is a simply beautiful film that feels like a true collaboration between two distinctly different artists. It’s really easy to say Steven Spielberg with all of his clout, even in 1982, took control over this film and bossed Tobe Hooper around. What seems more likely is that Steven Spielberg and Tobe Hooper made this film together over a shared love of childhood monster films. Spielberg took Hooper back to being a kid shooting 8mm films in his parents back yard and reading EC comics at night holding a flashlight, something they both had in common. In exchange, Hooper brought out horrific sequences that would be unheard of in just about any other Steven Spielberg production you can think of. Poltergeist was a monumental success for both filmmakers and for better or worse, Tobe Hooper was given access to a lot of money and a big picture studio deal for the first time in his career.

Lifeforce (1985) and Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986)

Well, what can one say about Lifeforce (1985) that is in any way going to do the experience of seeing it justice? What happened on this film, who knows. It has a legion of fans, but it’s an absolute mess of a film that feels like one part Alien knockoff and one part everything Tobe Hooper ever wanted to do but couldn’t afford. It all sounds absolutely fantastic for any monster kid on paper, and I’m not arguing that it isn’t a great time or has no cinematic idiosyncracies that are worth watching. Lifeforce is a special kind of disaster, and I would rather watch an artistic failure than a soulless consumer-driven product of a film any day.

LIke vampires? Tobe Hooper has you covered, but wait there’s more. Why not make them all sexed up and naked? Sure Tobe, go ahead. We’re also going to want to recreate the beginning of Alien with some nods to 2001 that’s really expensive but not really going to add anything to the film. Wait, what? Lifeforce is just one of those bonkers films that is often celebrated simply for how off-the-wall insane it truly is. A lot of people hate it, and it’s hard to blame them but it’s an absolute blast of a trainwreck where it truly seems at times no one is behind the wheel.

By the mid-1980s, the American slasher had become more than a subgenre. After John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) inspired Sean Cunningham to make a buck with Friday the 13th (1980) the floodgates were open. Slashers were cheap to make and easy to sell. They were mostly marketed to teenage boys who wanted to see some naked girls and a little bit of violence. It was an easy recipe and everyone was in on it. So why not Tobe Hooper? The only problem is he had already created one of the slasher “grandaddies” way back with Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Instead of designing a new slasher film to cash a check and lay back on a beach, Tobe Hooper got to thinking that why wouldn’t the Sawyers still be out there, just doing what they have always done in the backcountry of Texas. After all, last Leatherface was seen, he was pretty pissed off but certainly not defeated.

Tobe Hooper quickly decided it was time to take a trip back to the monsters he created with Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986). It is my unabashed favorite horror sequel of all time. Hooper knew there was no point in trying to copy what he had already done with the original film, and that doing so could just prove to be a potential monumental failure for the director. Instead, he took a look around and decided to infuse the Sawyers into 1980s pop culture. Instead of shooting TCM2 like a snuff film, it looked almost like a John Hughes (Pretty in Pink, Sixteen Candles) teen comedy. Speaking of comedy, Hooper subverted everyone’s expectations by parodying himself. There are almost as many laughs in his sequel as there are scares…almost.

Throw in a just-sober Dennis Hopper (who shot this and Blue Velvet the same year), Bill Moseley’s (The Devil’s Rejects) darkly hilarious portrayal of Sawyer family member Chop-Top, and ultimate scream queen Caroline Williams (The Stepfather II) and Tobe Hooper made a sequel that managed to stand all on its own. It may not have been the visceral revolutionary feel of the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but TCM2 had a style and swagger all its own that the series has never come close to matching since. Tobe Hooper never made another Texas Chainsaw film, but the two Hooper films spawned two more sequels of their own. In 2003, a popular remake of the original TCM, helmed by Marcus Nispel, kicked off the Hollywood horror remake craze itself. The remake to that film had a prequel and when that timeline was exhausted, it was time to retcon everything but Hooper’s original for a direct Leatherface only sequel. The retcon sequel worked for Halloween (2018) much better a few years later, but they had a much better script.

As recent as 2018, a film about the origins of Leatherface was made, meant to be a prequel to Tobe Hooper’s original Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Fractured, diluted, and unnecessary as all that may well indeed be, it’s just a taste of the direct influence of one of Tobe Hooper’s films. He continued to direct throughout the 1990s with less-received fare like The Mangler (1995) and the underrated Body Bags (1993). He also did a lot of television work throughout the ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s such as Tales from the Crypt (“Dead Wait”), Freddie’s Nightmares (“No More Mr. Nice Guy”), and Amazing Stories (“Miss Stardust”) His last feature Jinn (2013), was released in 2013 after a lengthy dispute over the film’s content from the United Arab Emirates. To the end, Tobe Hooper was always questioning authority and challenging the status quo. He is truly a master of horror and one of cinema’s greatest icons.

‘Lifeforce’ is absolutely fun and the very opposite of a ‘train wreck’. We’re so used to simple films with simple foci that many seem not able to enjoy a more far reaching, ambitious and genre inclusive film. ‘Lifeforce’ was way ahead of it’s time and if you didn’t like it you just don’t get it.

‘Lifeforce’ is absolutely fun and the very opposite of a ‘train wreck’. We’re so used to simple films with simple foci that many seem not able to enjoy a more far reaching, ambitious and genre inclusive film. ‘Lifeforce’ was way ahead of it’s time and if you didn’t like it you just don’t get it.